Researchers from the University of Minnesota established this flowering bee lawn in Kenwood Park in Minneapolis. Photo by Rachel Urick, University of Minnesota Bee Lab

Beekeepers have been reporting population declines since the late 1990s, and the numbers have only worsened since bee colony collapse disorder was officially recognized in 2006. As a result, over the past several years, awareness of the importance of pollinator populations to our planet has grown, and scientists, beekeepers and landscape professionals have been exploring various ways to protect pollinators and supply forage and habitat for them.

One fairly easy solution is to modify turfgrass areas to include pollinator food sources. A study published in 2016 showed that 2% (40 million acres) of the land in the lower 48 states is devoted to turfgrass. Much of that area is used for lawns, parks and golf courses, and a large portion of that acreage has the potential to become a haven for pollinators.

For residents of Minnesota, efforts to halt population decline in bees and other pollinators have moved to their hometowns and home lawns. Known as the “Land of 10,000 Lakes,” Minnesota is now on track to be the state of flowering bee lawns, which may not be as lyrical as the state’s nickname, but should boost the area’s pollinator populations.

Last May, the state stepped forward with a plan to pay homeowners to convert their lawns into bee habitat. The state legislature has authorized $900,000 to be spent over one year to allow homeowners to cover the cost of converting monoculture turfgrass lawns by adding flowering plants and native grasses to provide nourishment for bees. Participating homeowners will receive up to 75% of the cost of renovation. That amount rises to 90% of the cost in areas that have “high potential” to become habitat for the rusty patched bumble bee (Bombus affinis), a native species that received endangered status under the U.S. Endangered Species Act in January 2017.

Pollinators need support year-round. Julie Weisenhorn, an educator with the University of Minnesota Extension, shares some easy ways to make a landscape beneficial to pollinators throughout fall and winter:

Researchers at the University of Minnesota’s Turfgrass Science Lab and the University of Minnesota Bee Lab have been cooperating on pollinator research for some time and are working together on the bee lawn project — an effort to create more sustainable lawns that use eco-friendly lawn care practices and provide forage for bees.

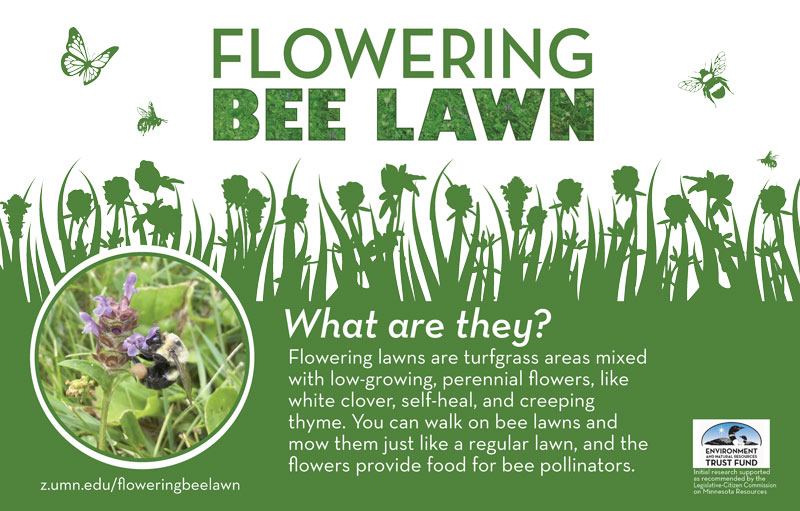

James Wolfin, a recent graduate of the university and one of the students involved in the bee lawn project, has helped develop a recipe for converting grassy areas at homes, parks and golf courses into “flowering bee lawns.” The turfgrass remains (for Minnesota, Wolfin prefers low-input fine fescues, but Kentucky bluegrass is acceptable), and native flowering plants are introduced to provide attractive, low-maintenance food sources for pollinators.

In Wolfin’s research, which began in 2016, the city of Minneapolis was divided into four quadrants. Each quadrant had two parks: one with naturally occurring Dutch white clover (Trifolium repens), and one “florally enhanced” park that had been seeded with a mix of Dutch white clover and two native flowering plants — self-heal (Prunella vulgaris) and creeping thyme (Thymus serpyllum). Turfgrass in the florally enhanced parks was scalped, the soil was aerated, and the area was seeded in late fall in low-traffic, shady areas with high visibility.

A baseline bee survey of the parks in the study was made in 2016 before seeding with native wildflowers, and bee surveys were taken at both types of parks after seeding in 2017 and 2018. Of the four parks that were seeded, the enhancements were successful in two parks in 2017 and three parks in 2018.

Over the three years of the study, 3,507 bees were collected, with 57 unique species found on Dutch white clover and 60 unique species on the seeded areas. Enhanced parks also had greater species diversity, and the bee communities on the white clover were distinct from those on the self-heal and creeping thyme.

Find bee lawn signs on the University of Minnesota’s flowering bee lawns page.

The research showed that allowing clover and flowering plants to grow in a low-input lawn or grassy area or seeding such areas with native wildflowers can provide forage for a diverse pollinator community. For golf courses, Wolfin suggests that rough or out-of-bounds areas (or perhaps the driving range) could be seeded with clover and native wildflowers to create pollinator-friendly areas. In all cases, wildflowers can be reseeded every three to four years if the flowers are not as dense as the homeowner or landscape manager would like.

For assistance in establishing pollinator-friendly landscapes, check out the publication Flowering bee lawns: A toolkit for land managers from the University of Minnesota, and visit the University of Minnesota Extension online. Additional information on creating landscapes for pollinators throughout the U.S. is available from the USDA.

Teresa Carson is GCM’s science editor.