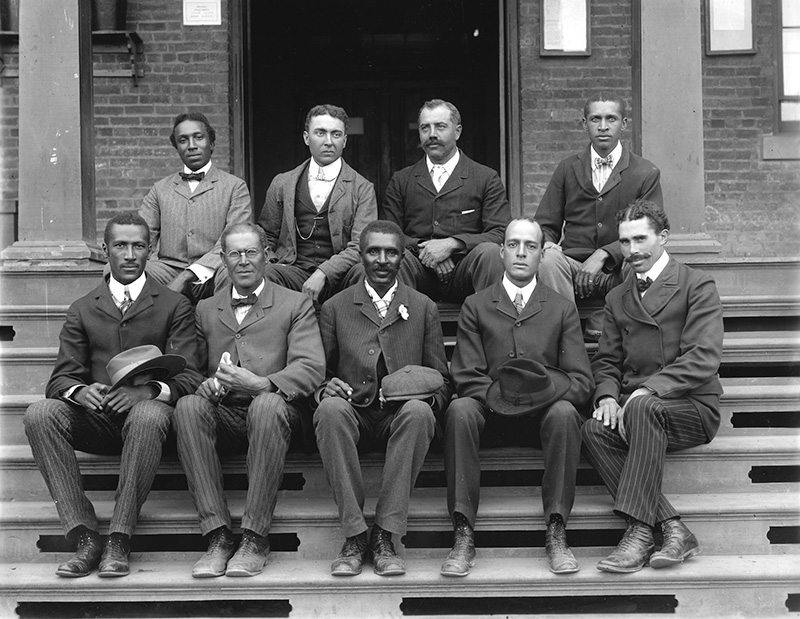

George Washington Carver (front row, center) on the steps at the Tuskegee Normal and Industrial Institute, with staff, ca. 1902. Photos courtesy of Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, LC-DIG-ppmsca-05633/Frances Benjamin Johnston

Well known for his contributions to agriculture, especially in crop rotation and peanuts, George Washington Carver also had a hand in the identification of various specimens of grasses and research into restoring depleted soils. Some of that work still

has an impact on the establishment and care of turfgrass today.

More than a century ago, Carver was in the process of establishing himself as a trailblazer in exploring new methods of farming to help those whose harvests were dwindling from depleted cotton fields.

The scientist and inventor, who was born into slavery, became interested in plants at a young age and went on to earn a Bachelor of Science degree at what is now Iowa State University in 1894. Two years later, he earned a master’s degree in agricultural

science, also from Iowa State. He went on to a decadeslong career of teaching and research at Tuskegee University. Through his teaching, research and outreach, Carver maintained his focus on helping those most in need.

“As a botany and agriculture teacher to the children of ex-slaves, Dr. George Washington Carver wanted to improve the lot of ‘the man farthest down,’ the poor, one-horse farmer at the mercy of the market and chained to land exhausted

by cotton,” says a memorial to Carver at Tuskegee University. “Unlike other agricultural researchers of his time, Dr. Carver saw the need to devise practical farming methods for this kind of farmer. He wanted to coax them away from cotton

to such soil-enhancing, protein-rich crops as soybeans and peanuts and to teach them self-sufficiency and conservation. Dr. Carver achieved this through an innovative series of free, simply written brochures that included information on crops, cultivation

techniques and recipes for nutritious meals.”

These achievements were hallmarks of his long career. But in his early academic years, Carver’s interests included the study of grasses, including some types that are familiar to greenkeepers today.

A special collection at the Missouri Botanical Garden — “The Grasses of George Washington Carver” — chronicles the early work he did in collecting specimens of grass in Iowa between 1894 and 1897. The Garden’s herbarium has

digitized nearly three dozen specimens, each noting where and when it was collected. Many are in the grass family (Poaceae), and the collection includes bentgrass, Junegrass, lovegrass, wild rye and others.

Carver went on to communicate his work through 44 agricultural bulletins. Most contain information that can be helpful even today, and perhaps could be implemented in the work of caring for a golf course. One in particular caught my attention: Bulletin

No. 6, “How to Build Up Worn Soils,” issued in 1905.

At the time, Carver was director of Tuskegee’s Experiment Station. Started in 1897, the eight-year study covered crop rotation, deep plowing, terracing and fertilizing.

“The field, 10 acres in extent, had but little to characterize it other than its extreme poorness, both as to physical and chemical requirements,” Carver wrote. Much of the site was covered in red and yellow clay, and some was “worthless

sandy soil. Much of the sand for plastering and laying bricks was gotten there.”

“We think it wise to state here that the chief aim was to keep every operation within reach of the poorest tenant farmer occupying the poorest possible soil — worthy of consideration from an agricultural point of view — and to further

illustrate that the productive power of all such soils can be increased from year to year until the maximum of fertility is reached,” Carver wrote. The ground was aerated through extensive plowing, and each year planted in cowpeas, oats, potatoes

and other crops, using rotation to improve the soil. Potash, phosphate, manure, lime, “swamp muck” and crop remains were added to the soil, year after year. Over time, crop yields increased, and profits became significant.

“The character of the land was noticeably changed,” Carver wrote. “Instead of the thin, gray, sandy soil, it began to look dark, rich and mellow, due to the gradual deepening of the soil and the incorporation of large quantities of vegetable

matter into it of which it was so much in need.”

Next month, as we reflect on the contributions of so many during Black History Month, let’s also note the work of George Washington Carver, especially his contributions to our knowledge of grasses and soil science. For more information on his work

on grasses, visit bit.ly/3VQ1vkZ. For more on Bulletin No. 6, visit bit.ly/3UQUrDw.

Darrell J. Pehr is GCM’s science editor.