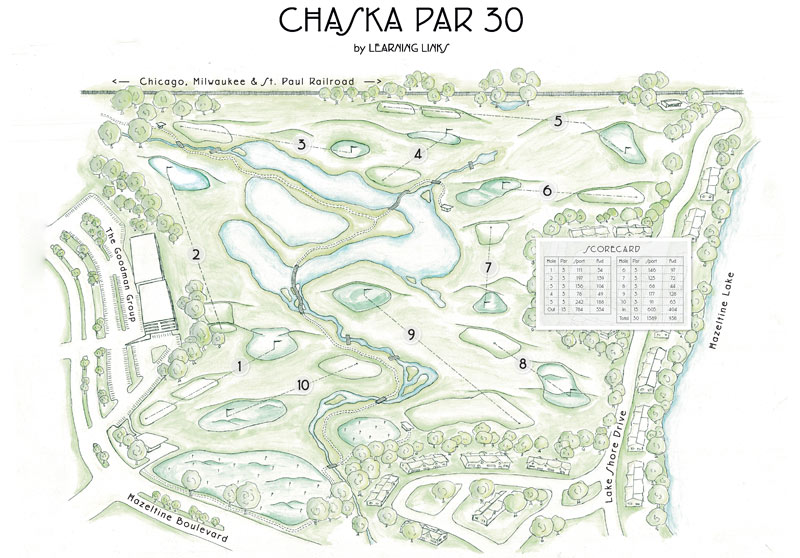

An aerial view of the Chaska Par 30 course in Chaska, Minn. Renovation work is scheduled to begin this spring on the 50-year-old Robert Trent Jones layout, transforming it from a nine-hole to a 10-hole course intended to be playable by golfers of all abilities. Photo by Brian Kirkvold, ExcelsiorAerial.com

After years of languishing in the considerable shadow of storied Hazeltine National Golf Club, the Chaska Par 30 was long overdue for a sprucing up.

“The course is 50-some years old,” says Mark Moers, GCSAA Class A superintendent who oversees the Chaska Par 30 and Chaska Town Course, both suburban Minneapolis courses. “Everything is old on it. The bunkers are bad, and the irrigation system hasn’t been replaced yet.”

The Robert Trent Jones layout had seen its rounds played drop nearly in half — from 30,000 annually 10 years ago to 17,000 — and was expected to spend about $500,000 to update its irrigation system and parking area.

Then along came the nonprofit Learning Links, whose founder, Tim Anderson, a longtime Hazeltine member, envisioned something more for the little par-3 muni literally on Hazeltine’s doorstep.

“Hazeltine is such an expensive and beautiful space. There are few places like it. It’s a great golf course for really great players. Alongside it is this little 50-year-old, untouched short course you drive by every time on your way in there,” says Susan Neuville, who serves on the Learning Links board of directors. “(Anderson) talked to people in the city. The city was ready to make some investment in drainage. He thought, ‘Why not come up alongside the city and make it even better?’ He thought in addition to what the city could already add, we could add the appreciation for the game. He thought there was a synergistic way to make that investment even bigger than just in the dollar sense.”

The result is an unusual public-private partnership to make the game of golf accessible to all.

Last September, the city of Chaska agreed to split the cost of a $1.5 million renovation project with Learning Links. Work is to begin on the Chaska Par 30 this spring, with reopening slated for late summer 2021.

The renovation is far from merely cosmetic.

“In early discussions with Learning Links, it became clear that our goal was to retrofit Chaska Par 30 to offer ‘barrier-free’ golf, without reducing fun levels for the existing customer base, and of course undertaking infrastructure upgrades,” says golf course architect Benjamin Warren of Artisan Golf Design. “Society has reached a point where accessibility is a pillar of every publicly funded building or infrastructure project. There are thousands of munis out there in need of investment. With golf on track to become a Paralympic sport, why wouldn’t cities step up and offer a few places that are designed specifically to cater to golfers with disabilities?”

What makes a golf course accessible?

According to the U.S. Adaptive Golf Alliance, there are 20 million Americans with physical disabilities who would like to play golf. But not every — or even very many — golf courses are accessible.

“Golf’s intergenerational appeal is a superpower. Adaptive golf is in that same ballpark,” Warren says. “Why shouldn’t a kid in a wheelchair be able to tee it up with their able-bodied buddies as ‘just one of the foursome’?”

E.Q. Sylvester has seen both views from that foursome.

A former businessman, Sylvester is a longtime golfer who was competitive in the world of amateur club events and once carried a handicap of 6. Not long after he retired, in 2011, he suffered a kidney infection, which turned into sepsis. He underwent 12 surgeries and spent 10 months in hospitals and rehabilitation.

Now he’s a triple amputee.

“We’re all committed to including disabled in the fabric of the community — and in the game of golf,” says Sylvester, who is chairman of the USAGA and is also on Learning Links’ design and programming advisory board.

What makes a golf course accessible?

“All of the playable area will be graded so carts can go anywhere a walking golfer can go. We’ll use one type of grass at different lengths and pay attention to getting the drainage right,” Neuville says. “By accessible, that means all playable spaces are available to all players, from the parking lot all the way through. The whole playing area will be graded so you can play in the same area anybody else is playing without feeling bored or being made to feel it’s less exciting.”

Click on the image to enlarge.

An artist’s rendition of the new-look Chaska Par 30. The course is designed to be “barrier-free” and accessible to all. A key component is its 10-hole design, which allows golfers to play a complete nine-hole routing while leaving the 10th hole available for group instruction or programming. Illustration courtesy of Artisan Golf Design

Warren seems to bristle a bit at the suggestion that “accessible” is synonymous with “easy” or “beginner-friendly.” The team was careful, he says, to ensure the Chaska Par 30 face-lift would be playable and interesting for golfers of all abilities.

“Some slopes or sharp features that are impossible to navigate via a golf mobility device such as a SoloRider present no problem to a beginner golfer walking with clubs,” Warren says. “The same goes for convoluted bunkering and soft sand. Likewise, playing a shot from a steep side slope while strapped to a SoloRider can be terrifying. A decent chunk of the Modified Rules of Golf is dedicated to dealing with situations where it might be impossible or unsafe for an adaptive golfer to make a swing. This is rarely a factor for beginner golfers.”

A barrier-free playing field

Steep grading, lack of compliance with the Americans with Disabilities Act and treacherous bunkers aren’t the only obstacles to golf for disabled individuals. Even if special-needs golfers can get around a course, that doesn’t necessarily mean they feel comfortable doing so.

“This is changing a little bit,” Sylvester says. “A couple of years ago, if a disabled person went to a golf course, they might not be welcomed. They might even be turned away. Also, often they don’t know where to get instruction. Instruction is really important. If they haven’t played before, or if they’re just returning from the hospital ... they have to get used to their new body. That’s why instruction is so important, so they learn how to do it, that they can do it.”

The new Chaska Par 30 plans to address those areas as well.

Currently a nine-hole course, the new design features 10 holes and intentional routing so that extensive group training can be conducted on the 10th and still allow golfers to play a full nine-hole round. Also included is a huge Himalayas-style putting green, which Neuville, as a new golfer and mother of five, sees as a potential big draw for all golfers.

“From my perspective as a new player, it’s an unintimidating course, somewhere I could approach and learn, while it’s still interesting for my husband, a more experienced player,” she says. “And it’s family-friendly. There’s an enormous Himalayas putting green. You can bring the young ones for an exciting putting experience on the putting green, and you can create some interest in chasing that little ball around.”

“Putting courses are the lowest common denominator in this game,” echoes Warren. “Anyone — regardless of skill or physical ability — can enjoy the feeling of trundling a ball across a putting green toward a target. There’s no better entry point to golf. Chaska Par 30 has a beautiful frontage on Hazeltine Boulevard. What better place for a town putting green?”

The Chaska Par 30/Learning Links vision isn’t limited to golfers with physical disabilities. In fact, the language is specific: The Chaska Par 30 is intended to be barrier-free.

“I take that to mean it’s open to anybody who has a physical handicap or is mentally challenged or is financially strapped,” says Moers, the superintendent and a 23-year GCSAA member. “You make an opportunity for everyone. I think it’s time to include more people. With golf going down a little bit, it’s good to have new and different players, players of different calibers playing.

“It’s the opportunity to play without the fear of being harassed, where you don’t hear, ‘Hurry up, you’re playing too slow,’ and it’s the opportunity for people with different abilities to play.”

Part of the operating agreement calls for Learning Links to administer and distribute 6,000 rounds a year for 25 years. Of those, 2,000 rounds are to be free of charge.

“We’ll be able to invite people to play at no expense. Another piece of this is to remove financial barriers,” Neuville says. “We’re not throwing everything out the window. But you’re there to enjoy the community. There are no expectations.”

Reimagining existing golf layouts

Part of what attracted Warren, the architect, to the project was its potential to serve as a model for future golf course renovations.

Warren sees developments like the Chaska Par 30 as crucial to preserving — and growing — the game of golf.

“Urban green spaces that welcome golfers are vital to the future health of the game,” he says. “There will never be more golf in cities than we have today. With rapid urbanization and the changing recreation patterns of city dwellers, any space that provides an ‘outdoor sport’ experience within the city limits shouldn’t struggle to find a customer base. If a group of muni golfers is ever faced with the choice of losing their facility to developers or campaigning for a redesign that enables nongolfers to safely share the property, there is no choice at all. Throw open the doors. Plenty of nongolfers are potential golfers. The arbitrary barriers to participation are created by us.”

The Chaska Par 30 had seen its rounds played drop dramatically over the past decade and was in need of updates to its drainage and parking areas. The unique partnership between the city of Chaska and the nonprofit Learning Links will result in more than just a cosmetic face-lift, however. Photo courtesy of the city of Chaska

The Chaska project is unique in that it’s a public-private partnership and in that it carries a relatively small price tag, both of which offer challenges.

“Learning Links and the city of Chaska bring different knowledge bases and skill sets to the table,” Warren says. “Team members have been drawn from each entity and are dovetailing to great effect. One of the key ingredients of affordable golf is low-cost construction. I’m inspired by projects like CommonGround, Rustic Canyon and Winter Park. There’s one unifying feature that makes these courses so popular: When resources are limited, architects can still get plenty of bang for the client’s buck by building cool green complexes and being sparing with bunkers. In Chaska, we’re keenly aware that we are stewarding taxpayer funds and charitable donations.

“Minnesota is a tricky construction climate, and we will be dealing with clay and peat. We hope that creating a cool, affordable and accessible product in heavy soils — staying well within our preliminary budget of $1.5 million — might inspire other cities to consider similar projects.”

And if it inspires someone with a disability to take up a game that once had seemed unwelcoming at best and maybe even impossible?

“As I thought about the adaptive element — which was outside of my understanding at the time — that seemed to hold so much more meaning,” Neuville says. “I met many players who returned to this game after an illness, or older players who maybe returned after a stroke, or people in the military. I met a number of these people, either finding the game for the first time or finding it again after an amputation or emotional or social limitation, and this course is designed so they can reach it and navigate around it. The impact this can have on their lives is so profound.”

Andrew Hartsock is GCM’s managing editor.