Annual GHG emissions in CO2e from turfgrass maintenance in Los Angeles County

Maintaining turfgrass landscapes — including mowing, irrigation and fertilization — is an under-recognized source of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. California has ambitious policies to reduce GHG emissions and improve local air quality; however, Southern California continues to be one of the most polluted regions in the world. To better understand the significance of turfgrass maintenance as a source of GHG emissions, we calculate the total annual GHG emissions in carbon dioxide equivalent (CO2e) emitted from maintaining turfgrass across Los Angeles County (LAC) by combining 1) a spatial analysis of maintained turfgrass landscapes with 2) behavioral data on the frequency and amount of mowing, irrigation and fertilization for each turfgrass zone — residential, commercial, public parks, golf courses, college campus and private parks, and cemeteries — and 3) published GHG emissions per area of turfgrass from each of these activities.

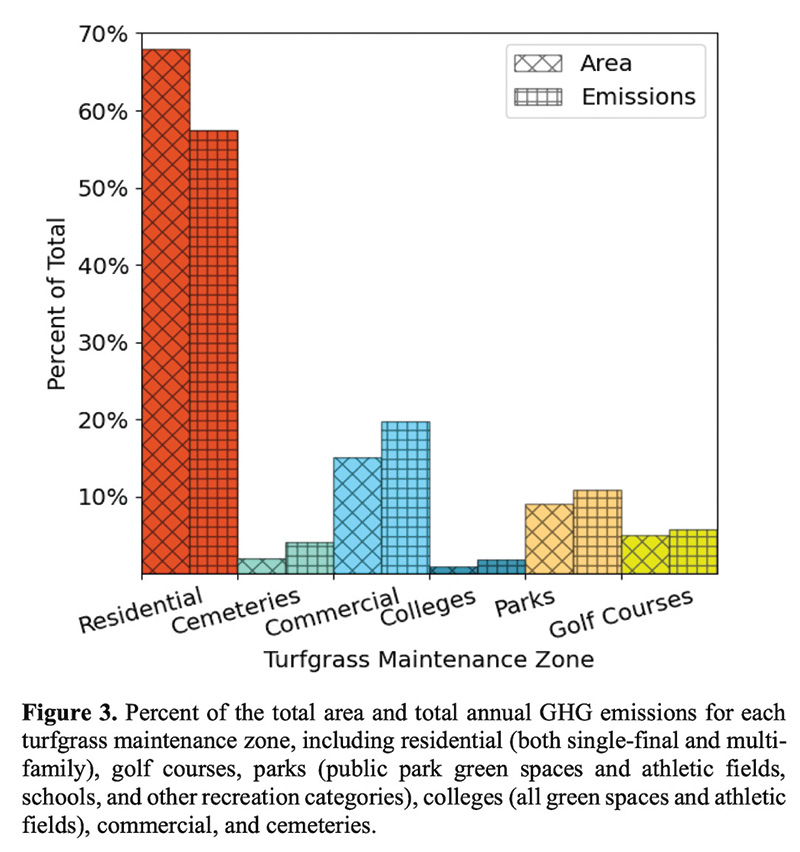

We find turfgrass maintenance in LAC produces approximately 536±176 metric kilotons of CO2e per year. Although college campuses/private parks and cemeteries had the highest emissions from maintenance per area per year, residential turfgrass landscapes are responsible for the most GHG emissions because they comprise by far the largest total area of maintained turfgrass in LAC. In contrast to previous work, which most often finds that mowing is the greatest source of GHG emissions, irrigation was the most significant source of GHG emissions in nearly all turfgrass zones due to the large quantities of imported water and variable terrain over which water is transported in the region. Findings indicate that reducing the total area of maintained turfgrass and the intensity of management could lead to significant reductions in emissions and support water conservation efforts in the state; however, turfgrass reductions should be focused on nonfunctional areas, with care taken to avoid furthering inequalities in access to urban greenspaces.

— Valerie Rountree (valerie_rountree@redlands.edu), Martin S. Hoecker-Martinez and Nathan W. Strout, University of Redlands, Redlands, Calif., and Michael Barnes, University of Minnesota

Research shows no differences in ‘penetrant’ and ‘retainer’ wetting agents

After several years of research, the results are in on the difference in turfgrass soil surfactants that are marketed as “penetrants” and “retainers.” Mike Richardson, Ph.D., professor of horticulture with the Arkansas Agricultural Experiment Station, says putting greens built following USGA recommendations with 12-inch-deep sand root zones require meticulous water management. Among the most important tools for managing water are soil surfactants, often called wetting agents. Wetting agents do not go through the same federal registration and labeling process as herbicides, fungicides or insecticides, resulting in less research data about what they are and how they work. In the absence of such data, marketing terminology such as “penetrant” or “retainer,” along with anecdotal evidence, have been used instead, Richardson explained. To address this, a study at the University of Arkansas was recently published by the American Society for Testing and Materials. Co-authors of the study include researchers at Texas Tech University, Ohio State University and Pennsylvania State University.

The study titled “Penetrants Versus Retainers: Comparing Soil Surfactant Terminology to Performance in Sand-Based Putting Greens” found that differences between soil surfactants marketed as “penetrants” or “retainers” were inconsistent, if present at all. Experiment station turfgrass researchers were led by Doug Karcher, Ph.D. Karcher, now at Ohio State University, was assisted by Daniel O’Brien, Ph.D., as a graduate student who served as lead author of the study. He now works for USGA. The study was supported by GCSAA. Multiple studies were conducted on creeping bentgrass and ultradwarf bermudagrass greens in Fayetteville, Ark., and Lubbock, Texas. Results reinforced the need to establish soil surfactant classifications based on performance data from field testing rather than marketing terminology. Co-authors were Joseph Young, Ph.D., Texas Tech University; Michael Fidanza, Ph.D., Pennsylvania State University; and Stanley Kostka, Ph.D., visiting scholar at PSU.

— John Lovett (jlovett@uada.edu ) University of Arkansas, Fayetteville

Darrell J. Pehr is GCM’s science editor.