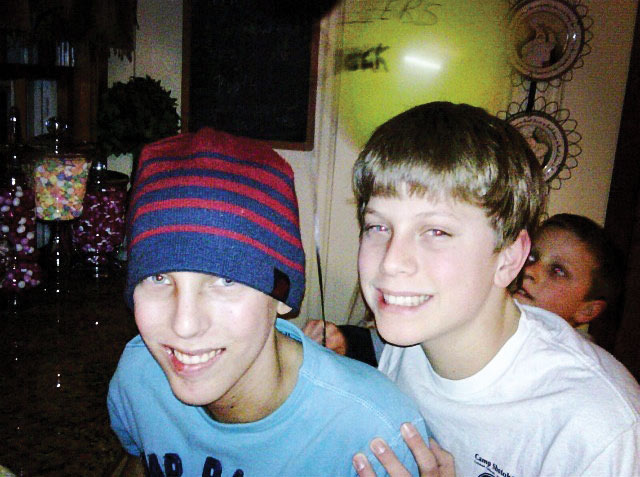

Snapshots from a life cut short: (top) Matthew Renk (left) with his twin brother, Tom; (bottom) Matt with his dad, Dave. Photos courtesy of Dave Renk

There’s no guarantee, of course, that Matthew Renk ever would have grown up to be a golf course superintendent.

Now, there were plenty of signs that he would, like the way he’d sit on the mowers with the golf course crew when he was too young to operate them, then run them himself as soon as he was able. Or the way he’d dress the part, with a little polo tucked into his little khakis, a radio clipped on his belt. Or the way he took to filling divots, or working bunkers, or the time he marched to a meeting with the president of the golf course on which he lived and his father toiled and announced that he fully intended to take over for his dad when the time came.

“He loved golf course work,” says his father, Dave Renk, GCSAA Class A superintendent at Lookaway Golf Club in Buckingham, Pa. “He was going to be a golf course superintendent from the time he was 5 years old.”

There’s no guarantee that story would have played out. Kids change their minds and their interests. Look no further than Matt’s twin brother, Tom.

Tom didn’t give a rip about golf course maintenance and spent his early childhood obsessing over dinosaurs and animals and pictured himself a marine biologist or veterinarian when he grew up. Now, at 25 and with a short but impressive résumé that lists stops as an intern at Pine Valley and Augusta National, Tom is the one following in dad’s footsteps as an assistant superintendent at Rolling Rock Club in Ligonier, Pa.

That might be the route Matt would have taken, paying his dues until it was time, as he prophesied, to take the reins from his father.

But as the tenses foreshadow, that’s not the case.

Instead, the Renks — Dave and wife Jackie, Tom and his younger brother Andrew — will gather once again this month at Lookaway. They’ll tee it up on the first hole, a short little par-4 framed by a stand of natural hardwoods and a lovely pond to the left, and they’ll deliberately, thoughtfully, at precisely 3:45 p.m., drive their balls straight into the water.

And as the balls make their slow, inexorable descent to the soft mud below, the Renks will think about Matt — about what was and what could have been, about the respite garden and the foundation that bear his name, about all that has transpired in the 10 years since his death as the result of a pediatric brain tumor — and they’ll mourn their loss, and they’ll count their blessings.

“It’s just a remembrance,” Jackie Renk says. “As time goes on, memories can fade. But we’ll never forget.”

Two tiny babies

Matthew and Thomas Renk were born, 12 hours apart, on Feb. 11, 1995. It was not a particularly joyous occasion — not because of the event itself, but the timing of it. Twenty-four weeks into her pregnancy, Jackie went for a routine checkup and was told she needed to get to an emergency room. Stat.

At that Philadelphia hospital, doctors scrambled to prolong Jackie’s pregnancy, but shortly after 3 that morning, Matt was born. He weighed just 1 pound, 14 ounces and had suffered a Grade 3 brain bleed. He was whisked away to the neonatal intensive care unit, or NICU. Doctors tried to keep Tom in utero as long as possible, but the drugs doctors used to keep Jackie pregnant made her dangerously ill, and half a day later, Tom — all 1 pound, 15 ounces of him — joined his brother in the NICU.

“The first 72 hours were excruciating,” Jackie recalls. “I wasn’t allowed to see them. Dave saw them briefly, and he said it was a pretty horrific sight.”

After a more than three-day stint in the ICU, Jackie was wheeled to the NICU to see her boys.

“The nurses warned me it would be tough to see,” she says. “They were worried about my well-being. The nurses told us we had to do a christening, because they were afraid they weren’t going to make it through the night. So we brought the grandparents in, did that. ... After that, they really started thriving.”

Of course, given such a dramatic and fraught entry into the world, simply surviving was a minor miracle.

The boys spent more than 100 days in the NICU — which Jackie visited 10, 12 hours a day, until Dave, then working as an assistant at Pine Valley Golf Club across the Delaware River in Pine Valley, N.J., could visit in the evenings after work. Tom went home first about the time of his expected due date; for another week, Jackie made the daily trek to visit Matt, still in the NICU, until he too came home.

“At that point, the house was like a hospital,” Jackie says, “with nurses coming and going.”

Doctors warned of developmental delays and said special-education classes were in the boys’ futures. The twins — fraternal (“They didn’t look anything alike,” Dave says.) — were 2½ when Dave, a 29-year GCSAA member, heard from a Pine Valley member that a new course, designed by Rees Jones in Bucks County, Pa., was being built. He got the job, and the family moved about an hour north of Philadelphia and settled. It was a grow-in both for the course and the family.

A recent photo of the Renk family — (from left) Jackie, Tom, Andrew and Dave — on the grounds at Augusta National.

“The kids loved growing up on the golf course,” Dave recalls.

“It’s all they knew,” Jackie adds. “They were here for the excavation at Lookaway. They watched the golf course being built. All they knew was hard work. We instilled that in them. And for Matt, it was a passion for him.”

The twins were together in kindergarten, but the parents decided to split them up for the rest of their grade-school years.

“They had their twin friends, and they had their own individual friends,” Jackie says. “They started to develop their own personalities, dressing to their own personalities. They were the odd couple. One was as neat as anything; Tommy was messy. But they worked together. They had that telepathy.”

The diagnosis

Perhaps it’s a disservice to fast-forward through a life cut so tragically short, but the abbreviated version is that Matt — and Tom and, eventually, Andrew, 3½ years their junior — grew up, seemingly healthy and happy, on that golf course.

Until one day, when the twins were 13, near the end of their seventh-grade year, they returned home from school. Matt, Tom reported, had thrown up on the bus. He had been having headaches, too, but the parents thought it might be stress, perhaps at the prospect of moving onto the next grade in school, or maybe he was battling a virus. They kept a close eye on him, and when he vomited again that weekend, they consulted their pediatrician and were advised to head to the hospital.

The rest is a bit of a whirlwind, with a CT scan confirming a tumor on the back of the brain, a diagnosis — pediatric medulloblastoma — and a hurried trip to meet with surgeons at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP).

“They said, ‘You have one option, and one option only. We need to operate, and we don’t know if he’ll survive,’” Dave says. “We come back from our meeting with the surgeons, and he’s sedated a little bit, and the first thing he said was, ‘Dad, am I going to die?’”

Matt survived the eight-hour operation, but it wasn’t a total success. Though surgeons were able to remove the bulk of the tumor, spots remained on the brain stem, and the medical staff targeted those with radiation.

Matt was in ICU for a month, then had to relearn everything, Jackie recalls: “It’s like when you’re 18 months old again, picking up Cheerios. They let him go home for the Fourth of July weekend, and I was following him around the house like he was an 18-month-old.”

Every day, five days a week, Matt and Jackie, mostly, made the drive to the hospital for physical and occupational therapy and radiation treatments — 33 rounds of it. Matt started eighth grade that September, then chemotherapy started in October.

The chemo, five rounds of it, was brutal.

“The drugs he took were just unbelievable,” Jackie says. “Within 30 seconds, he was vomiting unlike anything I’ve ever seen in my life.”

In all, Matt missed six months of his eighth grade year, but he was determined to return.

That March, just after he turned 14, Matt walked into Holicong Middle School.

“He was 89 pounds, just a walking skeleton,” Jackie says. “No hair on his head. Everybody respected him. But his hair started growing back, and he wanted to work with his dad ...”

‘The strongest kid I ever did see’

Matt was in remission for 14 months. He had five clean MRIs, but the sixth lasted longer than normal — 3½ hours — and Jackie’s intuition told her something was wrong.

“We walked out of CHOP at 11 at night,” she says. “He was a kid with no enemies. Everybody loved him. He was in the MRI so long … he said, ‘Mom, are you OK? I was in there so long.’ That’s just a snippet of who he was.”

At that, Jackie pauses. She gathers herself.

“He just ... took all this pain, and he took it like a trooper,” she says. “He was the strongest kid I ever did see.”

The doctor confirmed the tumor had returned. Jackie, furious, punched a wall.

“I freaked out,” she says, “but Matt said, ‘Mom, it’ll be OK.’ Dave was working. I told him, ‘You don’t have to go. Everything’s fine.’ But I knew he was suspicious. He kept calling us. When I told Dave, that embrace … him and his father … it was very painful to see. We knew. We knew that we were losing our hope.”

They nonetheless enrolled in a clinical trial, which involved chemo every day for a week. But Matt developed a cough, then pneumonia, and he was moved into ICU and pumped full of antibiotics.

He died within six weeks.

“This is so painful, but so empowering,” Jackie says around tears. “We were by his bed before they put him on the ventilator. Dave was there, and Matt said, ‘Mom, get dad.’ He said to Dave, ‘Dad, take care of mom.’ He didn’t want to leave this world until he knew I’d be OK. He wasn’t going to leave until he knew everybody, everything was in place.”

The day before Matthew Renk died, Dave took Tom and Andrew golfing.

“We didn’t hide anything from them,” he says. “We played golf, and I told them, ‘We have to get up early to go to the hospital. We have to say goodbye to your brother.’ There was no turning back. They were devastated.”

Dressed in their Lookaway clothing, the Renks were on hand as life support was ended. Matthew died in his mother’s arms, at 3:45 p.m., Aug. 10, 2010.

“When Matt was sick, Tommy said to me, ‘Matt’s in pain, mom. You don’t know how much pain,’” Jackie says. “It’s such a compounding experience for him, to be unable to see him. Now, 10 years later, does the pain go away?”

She answers her own question with a sob.

Payback time

During their many visits to CHOP, Dave and Jackie simultaneously acknowledged they were fortunate to be able deal with Matt’s illness financially — essentially, Dave continued to work, while Jackie bore the brunt of the caregiving — and that many other families were not.

“Right away, we thought, we have to do something to keep his name out there,’” Dave says.

That something, the Matthew Renk Foundation, was formed, “to provide much needed support to those facing the challenges associated with pediatric brain cancer.”

“There’s a disconnect, not on just the financial, but also the emotional part,” Dave Renk says. “There’s always another spouse who has to stay in the hospital, who can’t work. The hospital gets you vouchers for food and parking. But (the foundation) is for food, rent … you name it. The things you need to get by. And, also, to offer emotional support to other parents. We went through it.”

The Matthew Renk Foundation was founded in 2011. The “official” color of brain cancer awareness is gray (like Think Pink is for breast cancer), so the Renks first sought to trademark the term “Think Grey.” They sold sportswear bearing that slogan.

“We sold probably 2,000, 3,000 shirts that first year,” Dave recalls. “That’s how we started.”

The following year, Dave approached the Lookaway board of directors and asked whether the foundation could stage a fundraising tournament. He didn’t have high hopes.

“Lookaway is private — no outings. Zero outings. Nothing. So we had to get the support of the board members,” he says, “and it had to be unanimous. We asked if we could have a tournament in Matt’s honor. We figured it was a long shot. They were 100% for it. It’s a 200-member club. It sold out in 10 minutes.”

Lookaway Golf Club in Buckingham, Pa., where Renk family patriarch Dave has worked since grow-in.

There was a modest entry fee — in the range of $200 or $300, Dave says — and some members ponied up a few extra thousand here and there. The haul that first year? Around $40,000.

“We thought, $40,000? That’s amazing,” Jackie says.

The tournament has grown. One year, a member pledged $1,000 for every stroke under par for his team. His total donation was $20,000. Sponsors have been brought in. Vendors donate time and money.

Last year, the tournament netted $120,000, bringing the total to in excess of $820,000 in the foundation’s short lifetime. Close to 450 families have received money from the foundation. Families’ requests are vetted by a social worker at CHOP, and the requests are passed on to the foundation.

Payouts range from $1,000 to $3,000 at a time, Dave says, and families can make multiple requests — for anything from travel expenses to lodging to, tragically, funeral expenses.

The foundation also funded a respite garden on the sixth-floor roof of CHOP, which provides a relaxing greenscape as well as scenic views of the Philadelphia skyline. And it holds a yearly toy drive, with ties to the Philadelphia Association of Golf Course Superintendents’ winter party. Dave said some years that drive nets four or five pickups’ worth of toys for CHOP and its satellite offices. He estimates upward of 1,000 toys have been donated.

The Matthew Renk Foundation helped fund the respite garden atop a roof at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia.

“The outpouring of generosity has been just incredible,” Jackie says. “We’re so grateful to have this community that really believes in us and our cause. I think it’s because of Dave, too. He’s given his heart and soul to the golf course, and the membership wants to give back. They watched our family grow up there. They saw what Dave and I put into the course. You really are married to the course. It’s a different lifestyle, but we made it work.

“When I was in the hospital, day and night, sitting there, I thought, ‘We have to give back. How can we do it? We need to do something for the families in the line of fire.’ When Matt passed, I said, ‘I’ll keep fighting for you.’ That’s what I promised him. It’s who he was. I hope to keep this going as long as we can, keep going until the money runs out. Every year, it just seems to get bigger and bigger.”

A dream lives on

It’s no coincidence that Tom suddenly took an interest in golf course maintenance just after Matt passed.

“Growing up, my brother wanted to be a superintendent,” says Tom, a six-year GCSAA member. “I had no interest in it at all. I grew up on the golf course, and I’d still go on the course and stuff with dad and drive around, but I had no interest in turf at all. Once my brother passed away, I kind of wanted to keep his memory alive. And it helped me cope with it. When I was 15, I told my dad I wanted to take the steps to becoming a golf course superintendent.”

Right: Tom and Dave Renk.

Tom didn’t take the plunge right away. First, he dipped a toe, spending a couple of years working for Dave at Lookaway as he pondered his next step — enrolling at his father’s alma mater, Rutgers, and its two-year certification program.

“I wanted to figure out first if this was something I really wanted to do,” Tom says.

After “doing the basics” with Dave at Lookaway, Tom headed off to Pine Valley for an unofficial internship, then he joined the volunteer crew — alongside his dad — raking front-nine bunkers at the 2013 U.S. Open at Merion Golf Club. Then it was back to Lookaway to work for dad and a short stint with a golf course construction company.

He started at Rutgers in January 2016 and did his nine-month interim internship at Merion.

Two days after his graduation in March 2017, Tom started an internship at Augusta, just in time for the Masters, and he eventually was promoted to “turf graduate” — Augusta’s term for an assistant-in-training. He wanted a taste of the West Coast, so he spent five months as a second assistant superintendent at The Olympic Club in San Francisco, and then returned East. He’s now an assistant at Rolling Rock Club in Ligonier, Pa.

Asked about his ultimate goal, where he hopes to end up one day, Tom gives an answer that has an eerie yet comforting echo.

“I’d like to take over for dad,” Tom says, “when he retires.”

Careful what you wish for

It wasn’t until well after the fact that Dave Renk realized the motivation behind his son Matt’s Make-A-Wish request.

The Make-A-Wish Foundation grants wishes from terminally ill children between the ages of 2½ and 17, and Matt — undergoing treatments for brain cancer, specifically pediatric medulloblastoma — qualified. A fixture around the Lookaway Golf Club in Buckingham, Pa., where Dave Renk had been golf course superintendent since it opened in 1999, Matt had a fondness for golf course maintenance, so it came as little surprise when he made his wish.

Matt Renk behind the wheel of the John Deere ProGator utility vehicle he received from the Make-A-Wish Foundation.

Matt Renk behind the wheel of the John Deere ProGator utility vehicle he received from the Make-A-Wish Foundation.

While other youngsters often opt for a trip to a Disney property, or a meet-and-greet with a celebrity — John Cena is said to be the most requested — Matt went green. His ask? A John Deere ProGator utility vehicle. The only trouble was, the ProGator exceeded the Make-A-Wish Foundation’s $10,000 limit. Eventually, a deal was made with a local vendor who was able to find a good, used vehicle that somehow managed to come in just under the limit.

Matt was given the ProGator at a party attended by the Make-A-Wish folks.

“The Make-A-Wish people were floored,” Dave Renk says. “Normally, they never get to see the kids get their wishes. Usually the kids are at Disney, or they go to see John Cena, so the people running the Make-A-Wish program never get to be there.”

Though it made sense in the context of Matt’s love for golf course maintenance, something about the request nagged Dave.

“I thought, why are you picking that? He was 15 years old,” Dave recalls. “It took me a while, but I finally figured it out. I think he knew he’d have a short period of time. You couldn’t just ask for the cash. I think he figured out he could get that, then, when he turned 16, he could go sell it and go buy the truck he wanted.”

Andrew Hartsock is GCM’s managing editor.