Figure 1. Study plots on a TifEagle bermudagrass putting green one week after treatment applications.

Annual bluegrass (Poa annua L.) is the most troublesome winter annual weed in managed turf systems and has grown to epidemic proportions (1, 7). Having a light green color, it negatively impacts turfgrass quality through prolific seedhead production, clumped growth habit and lack of stress tolerance (5, 6). Controlling annual bluegrass can be difficult, as it exhibits high levels of genetic diversity, rapidly adapts to different climates and management practices, and has developed widespread herbicide resistance.

Current management programs rely heavily on herbicides for annual bluegrass control, even though few truly effective options are available (2). Frequent herbicide use with the same mode of action without implementation of other nonchemical management practices can lead to the evolution of herbicide resistance. Annual bluegrass currently ranks third among all herbicide-resistant species, with resistance to at least nine herbicide modes of action (3, 5). Therefore, alternative options for control are needed to reduce dependency on synthetic herbicides and to combat herbicide resistance.

Alternative nonchemical products are available for annual bluegrass control, but the effectiveness of these products has not been adequately tested in different turf systems and environments. There have also been untested claims about household compounds or homemade products being used to control weeds. Typically, natural or biological control options are nonselective, with all treated plants (desired or not) sustaining damage (4). Research is needed to further investigate different nonchemical commercial products and household compounds for turfgrass tolerance and their effectiveness to control annual bluegrass.

Materials and methods

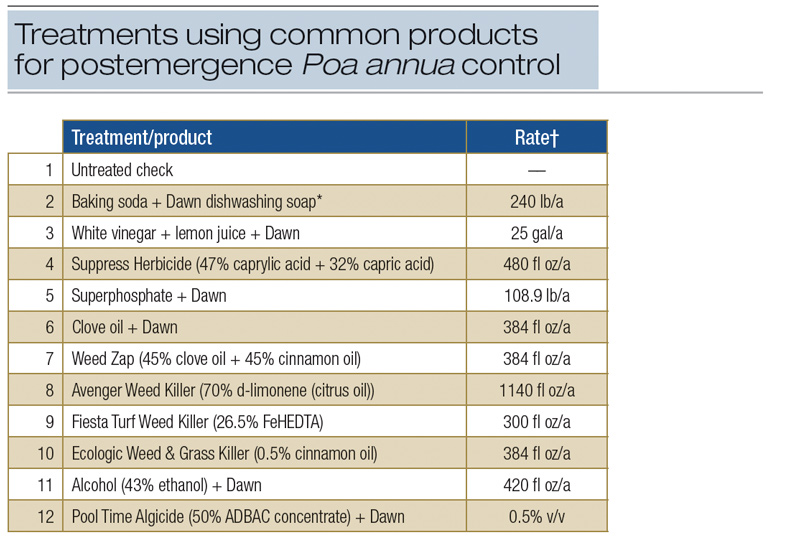

An experiment was conducted at Clemson University in Clemson, S.C., in the spring of 2020 (Year 1) and 2021 (Year 2) to identify and evaluate the effectiveness of potential nonchemical products and alternatives for controlling annual bluegrass. A TifEagle bermudagrass (Cynodon dactylon x C. transvaalensis) putting green (Figure 1) was chosen as the experiment site because of sufficient natural infestation of annual bluegrass present. This study included 12 treatments consisting of common household compounds (Table 1, below).

†Spray volume = 60 gallons per acre (561 liters/hectare)

*Dawn dishwashing soap applied at 0.5% v/v (volume/volume)

Table 1. Treatments using common products for postemergence Poa annua control.

Treatments were applied on March 30, 2020, and March 30, 2021, using a carbon dioxide-pressurized backpack sprayer delivering 60 gallons per acre (561 liters per hectare). Applications were made during spring green-up, typically when bermudagrass is most sensitive to herbicide applications. Plots measured 4.9 feet × 4.9 feet (1.5 meters × 1.5 meters) and were arranged in a randomized complete block design with treatments replicated three times. The site was maintained to normal putting green standards at a mowing height of 0.125 inch (3.175 millimeters) and with irrigation provided as needed to prevent wilting. Plots were not mowed during the study to better display results from treatments.

Treatments were assessed visually for annual bluegrass control and turf phytotoxicity one, two and four weeks after application. Visual control was rated on a scale of 0% to 100%, where 0% = no control and 100% = complete control. Phytotoxicity was rated on a scale of 0% to 100%, where 0% = no phytotoxicity, 30% = maximum acceptable damage level, and 100% = complete turfgrass death.

Results

Significant differences occurred between years. Therefore, results are presented separately by year. Annual bluegrass control from treatments was mostly nonselective and visually similar to the burndown observed after applying nonselective herbicides such as glyphosate, diquat or glufosinate (Table 2). However, results were relatively short-lived, with most products providing little to no long-term control.

During Year 1, only plots treated with Suppress Herbicide EC (caprylic acid + capric acid, Westbridge Agricultural Products) and Avenger Weed Killer (citrus oil, Avenger Organics) had visual control ratings statistically higher than the untreated check. Annual bluegrass control was most noticeable one week after treatment (WAT), with Suppress providing best control at ~50% (Figure 2, below) followed by Avenger at 20%. Results began to wane the second week after treatment, with significant control only observed with Suppress (23%). Annual bluegrass plants continued to recover, and by the fourth week after treatment, no statistical control differences were evident between treatments and untreated check.

Figure 2. Suppress Herbicide (480 fluid ounces per acre) one week after treatment in Year 1.

In Year 2, seven treatments had visual control ratings statistically different from the untreated check. Similar to Year 1, annual bluegrass control was most noticeable one week after treatment. Suppress, clove oil + dishwashing soap, Weed Zap (clove oil + cinnamon oil, JH Biotech) and Avenger provided best control at between ~57 and ~87% (Table 2). By the second week after treatment, results began to wear off, with significant control only observed with Suppress (~67%), clove oil + Dawn dishwashing liquid (53%), Weed Zap (37%) and Avenger (27%). Recovery from all treatments was observed by four weeks after treatment, at which time no statistical differences occurred between treatments and the untreated check.

Bermudagrass turf phytotoxicity was observed following the application of selective treatments during both years (Table 3). Phytotoxicity was most evident 1WAT in plots treated with Suppress and baking soda plus dishwashing soap, but phytotoxicity was only observed in plots treated with Suppress 2WAT during Year 1 (Table 3). No other treatment caused phytotoxicity above the acceptable level at this point in Year 1. The turf had mostly fully recovered by 4WAT.

During Year 2, phytotoxicity ranged from ~40 to ~85% 1WAT in plots treated with Suppress, Weed Zap, Avenger, EcoLogic Weed & Grass Killer (cinnamon oil, Liquid Fence Co.), white vinegar, lemon juice and ethanol (Table 3). By 2WAT, phytotoxicity above the 30% maximum level was only observed with Suppress (73%) and clove oil + Dawn (57%). Turf fully recovered by the fourth WAT with no phytotoxicity from treatments observed.

Conclusions

From this study, several non-synthetic chemical products tested could potentially provide some short-term annual bluegrass burndown. However, results were intermediate at best, with little to no long-term control from most products evaluated. None of the products tested appear to provide acceptable commercial control for this winter annual weed.

Certain products also caused short-term (one to two weeks) undesirable turf phytotoxicity. It is not recommended to apply the products used in this research for annual bluegrass control, as none are registered herbicides, and turf safety has not yet been adequately tested.

Additional research is needed to further evaluate these products for turf safety. Future research may also investigate application timing and optimal rate of such products for optimal weed control. Identifying a non-synthetic chemical product effective for annual bluegrass control that does not damage the desired turf would give a much-needed alternative to reduce synthetic herbicides use.

The research says ...

- Eleven nonchemical products were tested to identify and evaluate natural alternatives for annual bluegrass control to reduce synthetic herbicide dependency and to combat resistance.

- No treatment provided long-term control that was nonselective.

- Control was short-lived, with annual bluegrass recovery beginning approximately two weeks after applying treatments.

- Bermudagrass turf phytotoxicity from selective treatments was most evident one week after applying treatments, and turf had mostly fully recovered by four weeks after treatment.

- No suitable alternatives identified from products tested appeared to be as effective as current synthetic herbicide options.

Literature cited

- Cross, R.B., L.B. McCarty, N. Tharayil, J.S. McElroy, et al. 2015. A Pro106 to Ala substitution is associated with resistance to glyphosate in annual bluegrass (Poa annua). Weed Science 63(3):613-622 (https://doi.org/10.1614/WS-D-15-00033.1).

- Duke, S.O. 2012. Why have no new herbicide modes of action appeared in recent years? Pest Management Science 68(4):505-512 (https://doi.org/10.1002/ps.2333).

- Heap, I. 2018. The International Survey of Herbicide Resistant Weeds. www.weedscience.org. Accessed: May 4, 2020.

- Kerr, R.A., L.B. McCarty, J. Harris and S. McElroy. 2019. Alternative control options for annual bluegrass (Poa annua L.). Proc. 113th ASA/CSSA/SSSA International Annual Meeting, San Antonio.

- McCarty, L.B. 2011. Best golf course management practices. Third edition. Prentice Hall, Upper Saddle River, N.J.

- Murphy, T.R., D.L. Colvin, R. Dickens, J.W. Everest, D. Hall and L.B. McCarty. 2010. Weeds of Southern Turfgrasses. Clemson University Cooperative Extension Service, Clemson, S.C.

- Van Wychen, L. 2016. 2015 survey of the most common and troublesome weeds in the United States and Canada. Weed Science Society of America National Weed Survey Dataset (https://wssa.net/wp-content/uploads/2015-Weed-Survey_Baseline.xlsx).

J.W. Taylor, M.S., is a doctoral graduate student; L.B. McCarty, Ph.D., is a professor of turfgrass science; and R. Kerr, Ph.D., is a former doctoral graduate student at Clemson University, Clemson, S.C. Kerr is now employed with Bayer Environmental Sciences, Clayton, N.C.