Natural needle drop and exfoliating bark can add confusion to a diagnosis. Photos by John Fech

Call it triage, diagnosis or woody plant detective work — solving tree problems is a complex but necessary endeavor. Determining what’s wrong, what caused it and how to fix it is often a multifaceted effort involving distinguishing between signs and symptoms as well as biotic and abiotic influences. Once verified, sifting through and making choices from the available options for treatment can be as demanding as the identification of the causal agent(s). An eyes-wide-open, all-possibilities-on-the-table approach is the appropriate course of action.

Insecticide treatment for leaf-feeding insects.

Myths and realities of tree problems

Whether it comes from an uninformed member, a neighboring property owner or a social media post, there are many myths of tree maladies. In most situations, the people who put the fabrications out there are well meaning, but just not well trained in this arena. Some common examples include claiming the cause of the demise is insects that are over 1,000 miles away, the assertion that fertilizer will fix all ills, simply suffering from old age and perhaps the most misguided — “it just got sick this past month.” Getting to the real cause(s) is the ultimate goal.

Predisposing factors are long-term stressors.

What is it supposed to look like? Best starting point

Tree problems can be confusing, especially if there is a question related to the “normal” look of the specimen. Perhaps there is something in your mind that says, hmm … is this the way that this tree is supposed to look, or does it naturally look this way? In fact, this is the best starting point for diagnosis. Sure, a tree is supposed to have needles, leaves, flowers and a trunk and branches, but are they supposed to be green, yellow, white, twisted, thick, small, rumpled, stiff or floppy? If the normal look of the tree is overall green, with needles and shoots that are 8 inches long and the plant that you’re looking at has 2-inch brown and green needles at the ends of the branches, then it’s a good sign that something is wrong, and further investigation is necessary.

Speaking of signs, it may be a technical point, but the appearance of a plant: The color, shape, size and plant part droppage is a symptom, whereas the presence of a biological organism, such as an aphid, fungal mat or whitefly, is a sign. When communicating to stakeholders, it’s best to use the correct term to avoid misunderstanding.

Inciting factors add insult to ongoing injury.

Diagnosis can be straightforward or multifactor

Straightforward: Once you’ve compared the “normal” look of a tree to what you see in front of you, it’s possible that the cause of the odd or at least different look is a pest or causal agent commonly associated with the species, such as scab on crab apple, mimosa webworm or whiteflies on ficus. These influences are easily identified with a short conversation with a veteran staff member or a quick Google “site:edu” search.

In most cases, these causes are easily identified and controlled or explained. They’re not always effortlessly dealt with, but the determination is not complicated — more of a “one-off” kind of occurrence. These tree problems are initiated by acute influences, characterized by the rapid onset of symptoms, usually triggered by a single stressor, such as root severance or periodic drought, with recovery potential if provided with immediate and targeted intervention. As well, in the case of nipplegall on hackberry, minor herbicide drift or natural needle drop of pine, no significant control measures are needed.

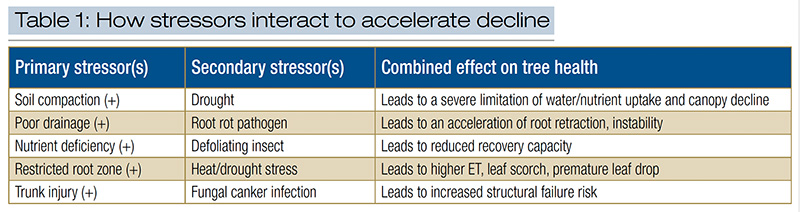

Multifactor: Difficult problems almost always involve more than one contributing factor, especially if the tree has shown atypical symptoms for more than a few months. They are characterized by the observation of a slow, progressive deterioration or chronic decline over several growing seasons or years. These issues are driven by several long-term influences, such as a combination of soil compaction, repeated drought and nutrient deficiencies. The earlier in the tree’s decline that these stressors can be identified, the more likely that they can be returned to health.

Contributing factors usually take advantage of an opportunity to inflict further damage.

Stages of difficult-to-diagnose tree decline

Though many tree problems appear to be simple one-time situations, in many cases there is a lot more going on that is not obvious at first glance. Four groups or layers are generally recognized.

1. Predisposing factors are long-term stressors that weaken tree health, such as stem girdling roots that limit the movement of water and nutrients in the vascular system; soil compaction that limits gas exchange and root growth between soil particles; chronic nutrient imbalance often driven by pH, which leads to persistent deficiencies or toxicities; species climate mismatch characterized by trees that are poorly adapted to local conditions or microclimates; restricted root volume, common in parking lots and near clubhouses; and poor drainage or overly wet soils, which, like compaction, limits oxygen availability.

2. Inciting factors are sudden events that trigger visible decline in already vulnerable, weakened trees. These include mechanical injuries, extreme weather events or sudden pest outbreaks. In most cases, if a given tree were not predisposed to weakness, the tree’s defense capacities would allow it to resist damage from an inciting factor.

Iron chlorosis can be a quick visual diagnosis.

3. Contributing factors are secondary insect pests and pathogens that accelerate deterioration. These may include decay fungi, opportunistic insects or secondary pathogens that usually do not normally colonize healthy tissue.

Terminal stage: When predisposing, inciting and contributing factors are present, a downward spiral often begins, which may result in a tree entering the terminal stage. Over time, they work together through sequential interactions to end a tree’s life, especially if any interventions were not taken or successful. In most situations, the terminal stage develops after several growing seasons.

Canopy dieback can occur for various reasons, but early observation is key.

Linking above- and below-ground symptoms — recognizing early stages of tree problems

To prevent the four stages of multi-factor tree decline, it’s helpful to be able to recognize the early stages of tree problems, often linking above and below ground symptoms. In most cases, it’s just a matter of routine inspection and monitoring; in short, being observant on a regular basis. For example, noticing canopy dieback, leaf color changes and stem elongation reductions are above ground symptoms that are characteristic of the beginning of serious problems. Below ground symptoms are also quite telling; observations of stem girdling roots, basal decay and surface root decay are influences that in combination with above ground occurrences usually send trees into a downward spiral. The sooner that intervention can take place, the better.

Repeated injury from mowing equipment causes a deterioration of root function.

Considering above-and below-ground stressors

Symptoms are often mistaken for causes. Accurate diagnosis requires tracing visible problems back to the underlying stressor, not stopping at the first indicator encountered.

The best decline management is prevention. Subtle influences and causes of stress — long before visible decline — often signal the need for site or cultural changes that can preserve tree health, i.e. poor soil drainage, adequate root volume a.k.a. critical root zone, soil compaction, cut roots during cart path installation, irrigation line installation, sudden weather extremes, scraped bark, etc. Construction activity, equipment use and improper maintenance can inflict acute injuries to roots, trunk and canopy. These events often trigger rapid decline in already stressed trees.

After repeated injuries, roots soften, decay and cease function.

On-the-course diagnostic check

When assessing a tree for problems and possible eventual decline, it’s best to systematically examine a multitude of factors. In fact, a simple checklist or intake form can be constructed with spaces to fill in information and notes on pertinent observations. As stated earlier, start with the species identification and the expected appearance of the tree. From there, the form should continue with categories and blanks to fill in including:

- Site conditions and history

- Available root zone horizontal space and depth

- Root zone health and soil profile specifics

- Root collar/root plate condition

- Trunk diameter, taper and branch structure

- Canopy density, color and distribution

- Presence of pests, pathogens or injury

- Timeline and progression of symptoms

- Evidence of predisposing, inciting and contributing factors.

The influence of compaction and dry soils often leads to tree problems.

Steps forward — landing the plane

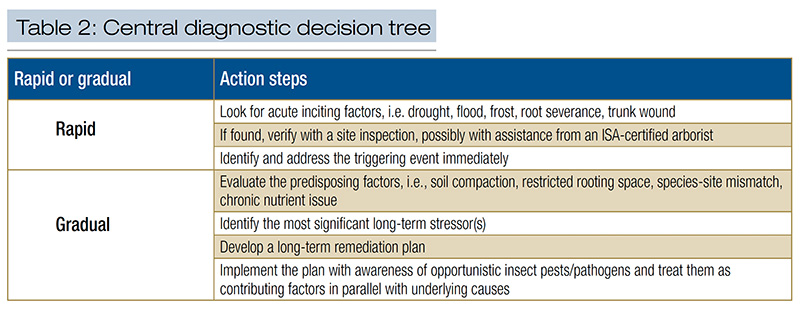

To bring all of these considerations full circle — abnormal/normal appearance, predisposing/inciting/contributory factors, abiotic and biotic influences, above- and below-ground symptoms, spiraling developments and regular monitoring/documentation — having a handy tool/decision tree for diagnosis in the glove box or on the utility cart, an “If this, then that” one-pager, can be very helpful. Boiled down, after the, “Is the tree supposed to look like this?” question has been answered, one central question remains as the logical next step forward.

John C. Fech is a horticulturist and Extension educator with the University of Nebraska-Lincoln. He is a frequent and award-winning contributor to GCM.