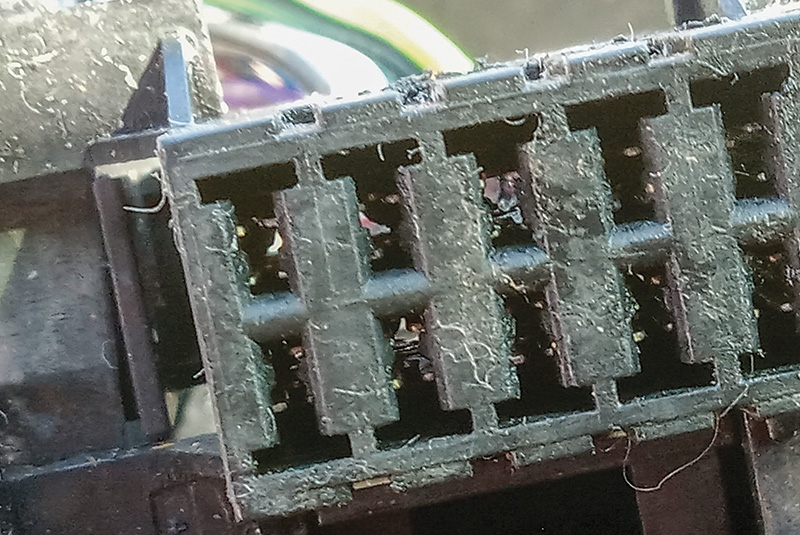

A blob of insulating dielectric grease can be seen in the top row’s third socket from the left in this electrical connector found in the failing instrument cluster circuit of a quarter-century-old vehicle. Further cleaning and installation of conductive grease solved the problem. Photos by Scott Nesbitt

If you like to argue, debate and gamble, continue lathering dielectric silicone grease onto electrical connectors you deal with. You might make things worse, especially if the work piece involves a computer that controls machine systems.

Here’s what Grok Artificial Intelligence (from X, the former Twitter) says: “… dielectric grease does not conduct electricity; it is an insulator designed to protect electrical connections from moisture and corrosion. It should be applied carefully to avoid interfering with electrical contact.”

If true, why does a website dealing with trailers publish the statement, “Dielectric grease is a great product for trailer plugs,” and post a video showing how to fill the cavities of a seven-pin trailer plug with dielectric grease? Contrarily, why would dielectric maker Newgate Simms Ltd. post an article headed “Not recommended — silicone grease use on electrical connectors.”

A few observations:

Electrical circuit connectors depend on solid metal-to-metal contact. In typical connectors, whether single- or multiple-wire, some kind of spring pressure squeezes two pieces of metal together. You can feel if a connector is good by the effort it takes to push it together.

Silicone grease is a lubricant, making it easier to couple the connector. The grease seals out water that stimulates corrosion. In a happy world, there’s enough internal spring pressure to push the grease aside and get good metal-to-metal contact.

However, clumsy handling, age and vibratory metal fatigue can reduce the spring pressure. A layer of dielectric grease can get between the metal pieces, cutting the circuit. Various physics sources say 500 or more volts is needed to punch through dielectric silicone grease. Yet, vehicle electrics are usually 12 volts, and computer controls run at 5 volts or less. Can you count on good electrical performance from a computerized vehicle if even a tiny bit of dielectric gets in the way?

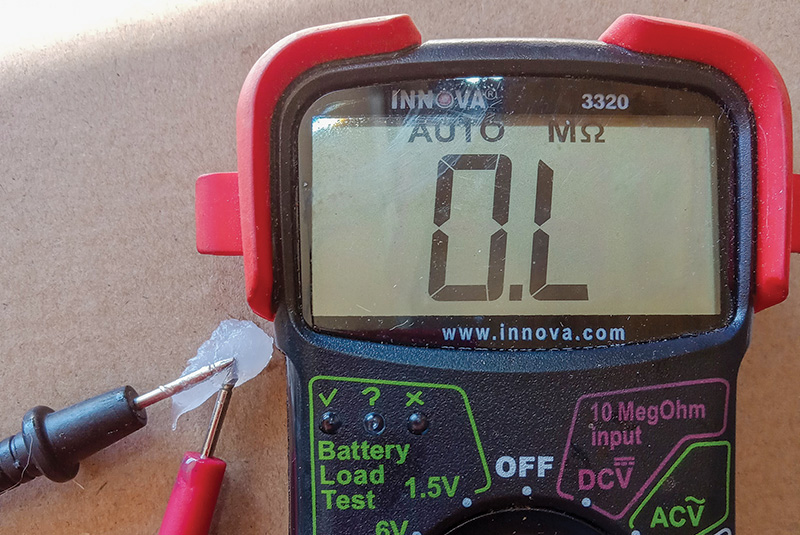

Dielectric grease blocks current flow when the multimeter’s probes are in light contact, reflecting the situation that can happen when this insulating gel is put into electrical connectors. In this demonstration, current flowed when the probes were pushed together, simulating the spring pressure found inside connectors.

This debate came to me when a 2000 Jeep Cherokee came in. The instruments and dashboard lighting would blank out every now and then — a known issue on these Jeeps. Removal of the cluster revealed that two 10-pin power plugs, and their corresponding sockets, were loaded with silicone grease.

The grease was cleared out with denatured alcohol and lots of compressed air. Then a hypodermic needle (from the farm supply store) was used to inject a tiny drop of non-dielectric conductive grease into each of the 20 ports. Care was taken to avoid creating a trail between two circuits in the plugs. It worked.

Conductive grease was not carried by my local auto part and hardware stores; an electrical supply house carried it. It can be found online. Different brands of this stuff contain tiny particles of copper, carbon, silver and other conductive materials. It solved my problem, and it could be worth adding some to your electrical repair toolbox.

Scott R. Nesbitt is a freelance writer and former GCSAA staff member. He lives in Cleveland, Ga.