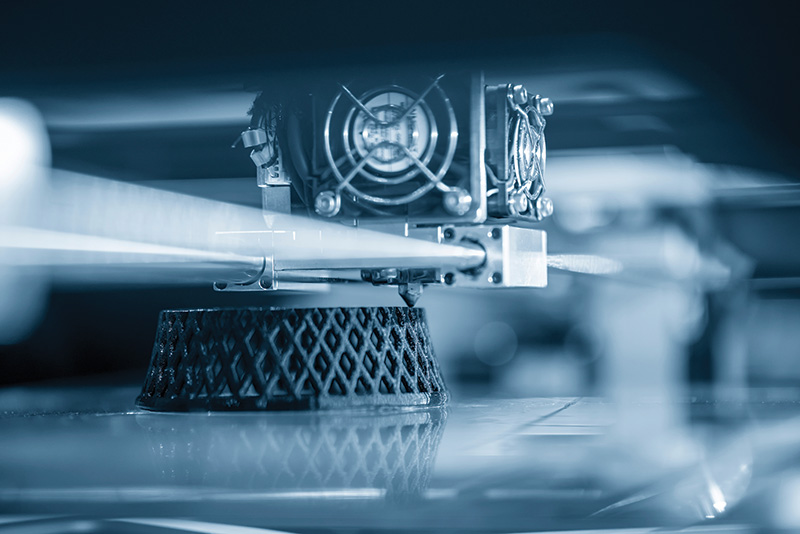

As 3D printers have become less expensive, turf industry professionals have used the technology for many on-the-job applications and practical shortcuts. Photo by Phuchit Aunmuang

When he was assistant superintendent at Coyote Creek Golf & RV Resort in Sundre, Alberta, Marcus Blech noticed a trend, primarily with the course’s seasonal staff, that was as frequent as it was annoying.

Time and again when crew members were sent out with the course’s hover mowers, the workers would return with the machines inoperable and the mowing undone.

“I think they thought they could break it and get out of doing the work,” says Blech, a three-year GCSAA member.

There had to be a better way, Blech reasoned.

A tech-savvy tinkerer at heart, Blech reached for his calipers and got to work. Rather than buy the offending part, he was determined to construct it instead, and with a little trial and error, he eventually settled on 3D printing as the solution.

“I could print the item for 10, 15 cents’ material, plus the time it took to print,” says Blech, who since has moved on from Coyote Creek and is now tending to municipal sports fields. “Before, you’d have to order the part,

and with COVID and everything, that would delay it a week or longer, and the flymo would be out of service the whole time. Now, if it broke, for cents — literally cents — and maybe half an hour on my printer, I could print out a few ahead

of time. If it broke, I could have it up and back in service in 10 minutes.”

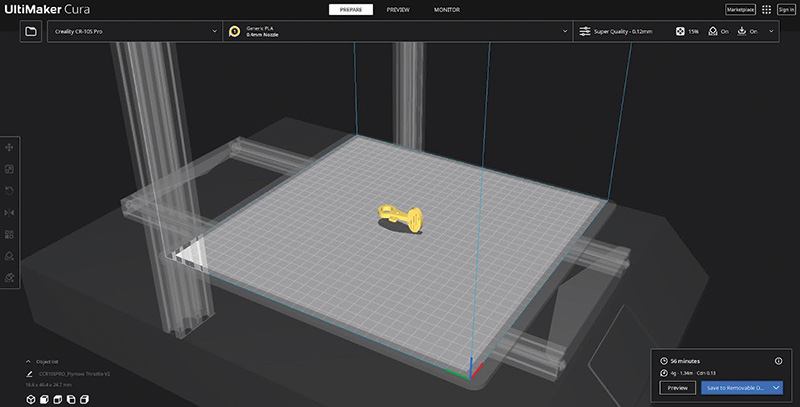

Three stages of the fly mower thumb throttle lever printed by Marcus Blech. Part one: The part in the “slicing” program that converts the 3D model into a layer-by-layer print. Photos by Marcus Blech

Blech, who says he bought his first 3D printer around 2019, is one of a quickly growing group of folks who are learning that 3D printing can be a unique solution to ever-increasing problems in the golf maintenance industry.

“More and more people are starting to use 3D printers in the industry,” Blech says. “And as more and more people start to use them, those files become more readily available.”

Which means, of course, more and more people can start dipping their toes in the 3D printing pool, which means more applications, which means more users, which … well, you get the idea.

“Like everything, the technology is growing so fast,” says JR Wilson, CTEM, equipment manager at Noyac Golf Club in Sag Harbor, N.Y., and a nine-year association member. “One of the things we talk about it is, if you want to be a technician

now, you almost have to think about 3D printing.”

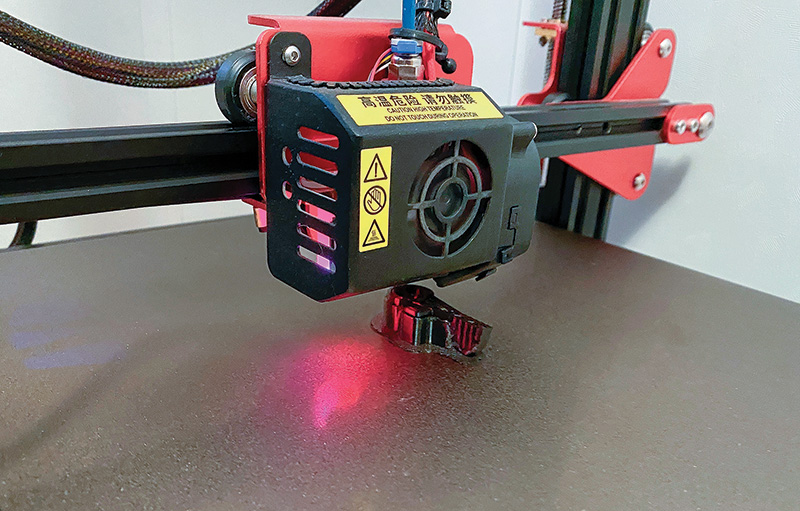

Stage two: The throttle lever being “printed.”

A third dimension

Technically, nearly all printing is three-dimensional.

Take a standard computer printout: The printer lays an almost immeasurably small layer of ink atop the page. The added ink, albeit miniscule, onto the page gives it depth — the third dimension — though the effect is markedly two-dimensional.

Now, imagine the printer could print the same shape — say, the letter W — on the exact location, over and over, and that the printhead could increase its distance from the page with each printing, over and over again. With enough printings,

the W would “rise” from the page, a 3D wonder one could hold.

Ink, of course, isn’t the best medium, and it probably wouldn’t make the most durable flymo throttle lever. Industrial printers can “print” in several media. Some of the most exotic applications include concrete (at least one startup

is 3D printing turnkey homes), cell-derived meat (yum!) and metal.

But plastics is where it’s at for the home — or golf course — hobbyist.

Stage three: The finished product

“When I started off, it was just a curiosity,” says Cory Phillips, EM at Atlanta Country Club and nine-year GCSAA member who includes 3D printing as part of the “What Can You Do with Today’s Technology” session at the GCSAA

Conference and Trade Show that he co-teaches with Wilson. “I know (2022 Edwin Budding Award winner) Trent Manning was doing some CNC router work, for bag tags and signs for courses, so I started looking into it, and that led me down the rabbit

hole looking into 3D printing.”

While computer numerical control routing is subtractive, removing material from, say, a wood or metal block to form a new shape, 3D printing is an additive process.

“When I first started looking at it,” Phillips says, “I thought it would just be astronomically priced to get into. But it’s not. It’s a very cheap hobby to get into. There’s lots of free software, lots of free designs.

And plastic is really cheap. You can make mistakes and fail and play with software and design and get it right without it costing much.”

3D printing has followed a familiar technological arc. The first printers were slow, clunky and pricey. Now, a solid, entry-level printer can be delivered next day to your door for less than $200, and a 1,000-foot reel of polylactide (PLA) filament, the

most widely used plastic material in 3D printing, goes for under 20 bucks.

A 3D printed pliers organizer Hector Velazquez says he uses every day in “Hector’s Shop.” Photos by Hector Velazquez

“It’s so inexpensive,” says Wilson, who first dabbled in 3D printing as a project with his school-aged son before realizing the countless golf-maintenance applications around the shop. “You can get a starter setup with materials

and a couple of rolls of material for under $400. Once you start fooling around with it, you can upgrade your printer, too. It’s almost like a hot rod or a car. You can buy the base model, then add things to make it better.

“But you can do a lot with just the base model.”

‘It’s like printing money’

Hector Velazquez — yes, that Hector Velazquez, the YouTube technician influencer, creator of “Hector’s Shop” and the technical as well as creative force behind (among other things) GCSAA’s “Inside the Shop” video

series — is a 3D convert.

For about two years, using a hand-me-down printer from Wilson, Velazquez has been “playing around” with 3D printing, and he continues to be amazed by its applications.

“It’s like printing money,” gushes the technician celebrity and 2018 Budding Award winner who also is a regular, not to mention wildly popular, presenter at GCSAA’s Conference and Trade Show. “It’s one of those deals

where I was like, ‘OK, how come we haven’t gotten into this before?’ To see something literally printed before your eyes … I 3D-printed a crescent wrench. It wasn’t that I printed the parts, then put it together. It

literally prints a crescent wrench. It works off the table. That’s crazy, right? I’m thinking, ‘This is nuts. There are so many things you can do with this.’”

Like what?

Well, while the possibilities are endless, there seem to be two approaches to 3D printing.

The more difficult path — actually fabricating something out of nothing — is the one Blech took with his flymo throttle lever. By carefully measuring and copying an existing part, he was able to create a suitable copy in computer-aided design

software. In this case, Blech worked in Tinkercad, a free, popular title that is powerful yet approachable enough that it’s often the CAD software of choice for school classrooms.

“I wouldn’t say it’s a steep learning curve,” Blech says. “I first had to learn how the software works, then just started building shapes in Tinkercad. That took the longest. That took probably a good two hours. Then there

was some trial and error. Sometimes they don’t print out exactly as you think they should.”

Aerosol can holders printed by Hector Velazquez.

The discrepancy in Blech’s case was traced to the slicing software, or the step between the CAD and the print. After a design is made in CAD, that model goes to a “slicer” (there are several free versions available) that, true to its

name, takes the completed 3D design and slices it down, telling the printer what and where to print on each layer.

But one needn’t fool with CAD at all. The second path to 3D-print success skips that step. There are millions — no joke — of 3D print files readily available online. The largest repository, Thingiverse.com, boasts nearly 2 million downloadable

models. Most contributors make the files free but restrict them to noncommerical use: Users can print and use all they want but can’t sell them.

Does anyone really need a 3D-printed, articulated octopus (the seventh-most-liked model on Thingiverse) or a Baby Groot (No. 15)? Of course not.

But Velazquez continues to be astounded by all the helpful models he has stumbled upon — and printed. While there are countless gazillions of geegaws and doodads available from Thingiverse (or the scads of other online sources, some free, some pay-to-print),

there are also oodles of things whose utility is obvious.

“When I got my printer from JR, I was like a little kid,” Velazquez says. “You can download all these files for free. I’m using all this 3D-printed stuff now. I have a 3D-printed drill bit holder. I have wrench holders all 3D-printed,

a hex bit holder, vernier caliper holders, aerosol can holders. OK, how realistic is this? Is this just something that’s cute, that you print and, there you have it, it’s just junk? Dude, it’s been well over a year now that I’ve

had these wrench holders. I still use them in my shop every day. Pliers holders — still have that. You add all this up, what would it have cost me to buy all this stuff? It’s just nuts. It would have been well over $200 to buy this stuff

from Snap-on or NAPA or AutoZone. I bought a spool of filament from Amazon for, like, 30 bucks. And I still have some from the spool left over. I could print it all over again.”

“I’ve made a bunch of things — tools, parts bins, tool holders — that just make my job easier on a daily basis,” Wilson adds. “There are so many things you can do with a 3D printer that are great for golf course maintenance.”

Why buy when you can build? It cost Cory Phillips mere pennies to print this wrench sorter/holder. Photo by Cory Phillips

Truth be told, there’s a third path to 3D happiness, too, that’s a combination of the other two. Users can start with a base model, either fabricated in CAD or downloaded, and customize it. Parts bin doesn’t quite fit in that drawer?

Stretch it in software and print it again. Cup holder doesn’t quite fit on the fairway mower? Tweak it and make it fit.

Another good example comes from the Canadian father-son duo of Greg and Will Hollins. Greg Hollins, Canadian GCSA Master Superintendent, GCSAA Class A superintendent and eight-year GCSAA member, and his son, Will, had a successful entrepreneurial run

designing and printing “small solutions for the golf course turf maintenance industry.”

Key Components 3D Printing and Design’s flagship product was a sprinkler-head key, available for Toro and Rainbird sprinkler heads, that was custom-designed to be light, pocket-sized, durable and affordable. The pocket keys could even be customized

with, say, a course’s logo. The Hollinses sold the keys to dozens of buyers in Canada and in more than a handful of states before shuttering the company. They quit not because the idea was impractical but because the elder Hollins changed jobs

and the younger headed off to turf school at Olds College, rendering them too busy to tend to the store.

“Dude, your head starts spinning with what you can do,” Velazquez says. “I see this now as, ‘OK, why doesn’t every shop have one of these?’ When it was new technology, people would freak out. It was expensive at first.

Now it’s becoming a common thing.”

JR Wilson has printed several simple items that “just make my job easier on a daily basis,” he says, like these small-parts bins. Photo by JR Wilson

What’s next?

It would seem that three-dimensional printing could be on the verge of a big breakthrough in the field of golf course maintenance.

Consider the arc of the use of unmanned aircraft systems — you know, drones — on golf courses. Just a few years ago, drones were expensive and impractical. Few folks could afford them, and their utility in the golf course world was limited.

Today, they’re cheap(er) and easier to fly, and the more people use them, the more uses they find for them.

It’s impossible to see, of course, what might be next for 3D printers as they become cheaper and more powerful, but multiple glances into the crystal ball reveal a common vision.

“I think it’s only a matter of time before manufacturers make plans available online,” Wilson says. “What if you’re trying to make a Toro (irrigation) head key? You’re tired of losing them. It’d be cool if Toro

would sell you a thumb drive or let you download a file where you could print as many as you wanted. That’s the thing I see coming. I’m not sure when, but it’d be neat to do that.”

“I think it depends on demand,” Phillips says by way of answer. “All it will take is one manufacturer doing it, then all the others will have to do it, too. But I think it’s coming. I think manufacturers, if supply chains keep

doing what they’re doing, individual workers are going to find it harder and harder to source the parts they need. And it’s good for the manufacturers, too. Instead of stocking a lot of small, plastic parts, you can just sell the file

and you can print the part yourself. From a technician standpoint, I can say I have all their plastic parts in my storeroom. That’s where I see this going.”

Even if that day’s in the unknown future, the users of today have more than enough to keep their printers humming.

“There’s just so many things you can find or come up with to make your job easier,” Velazquez says. “Literally for pennies and a little bit of time, you can get started overnight, come back in the morning, and you’ve got

a bunch of parts printed out. Once you get into it, it’s just endless. If you put your mind to it, you can do all kinds of things.”

Andrew Hartsock (ahartsock@gcsaa.org) is GCM’s senior managing editor.