Brian Youell at Uplands Golf Club in Victoria, British Columbia, where he has been at the agronomic helm since 1981. The club welcomes a PGA Tour Canada event every June, and has hosted a total of 15 Tour events. Photo by Chad Hipolito

On a sunny afternoon in summer 2012, I was driving the scenic marine route in Victoria, British Columbia, with my family. I pulled into a gas station, and while filling up the car, I looked inside at my wife and two young daughters and said, “Do you really want to know the truth? Do you really?” I held the gas pump handle over my head and motioned with a lighter that I could end it all right then. My wife and children were petrified, crying and unsure what to do. This is a moment in our family’s history that we’ll never forget, and, unfortunately, it wouldn’t be the last like it.

What had happened to my life? I had a wonderful family, great friends, a 30-plus-year career at the same golf course — Uplands Golf Club in Victoria — and no history of depression, yet my life was out of control. I woke up every day truly feeling like it was going to be my last, and my family knew it.

The accident

Flash back to April 14, 2010, when I was helping a fellow superintendent fix his irrigation system. I was approximately 30 yards away from a golfer hitting a wood when I took a line drive just above my right temple. I suffered a traumatic brain injury. There was a time when I couldn’t even remember my birthday or the names of my children, or add up dice while trying to play a game. I first shared my story of the symptoms and challenges of living with a traumatic brain injury in an article in the September 2011 issue of GCM.

Unfortunately, my condition declined rapidly after the article was published. Almost two years would pass after the accident before a specialist determined my brain had lost the ability to filter out information. My brain was trying to process everything at once — conversations, colors, noise, motion. I would sit at the dinner table and listen to my family, hearing their words but unable to make any sense of what they meant. I struggled just to get through a day, and the seriousness of my situation was becoming life-threatening.

I tried to hide my deficiencies from everyone, including my loved ones. My wife, Pamela, has multiple sclerosis, and I didn’t want to cause a further decline in her health. My family eventually became aware of my mental state, however, and their concern for my well-being heightened. One day, I came home to find my wife sitting next to the front door, sobbing uncontrollably. “I wasn’t sure if this was the day you were never coming home,” she said. She knew I was in a fight for my life — a fight that I was losing. My 9-year-old daughter would cry, “I wish I had my old dad back.”

Traumatic brain injury: What’s going on in the brain?

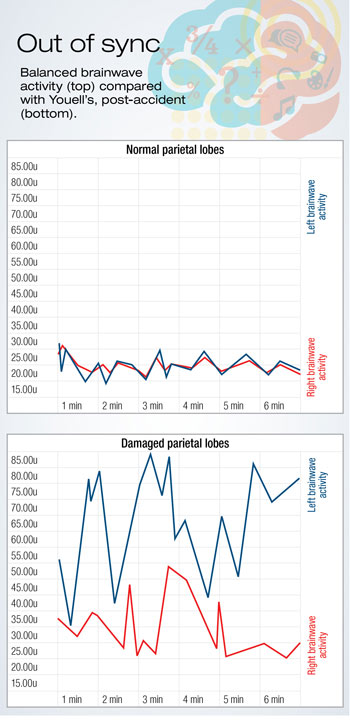

I’m not a brain specialist, but I’ve sure learned a lot about my own brain and how it works. To the right is an assessment of normal brainwave activity in the parietal lobes, which are part of the cerebral cortex and integrate sensory information. If the right and left brainwave activity are overlapping, an individual can process incoming information, organize it, and determine what to do next. The brain doesn’t consume much energy in this state.

After the accident, my brainwave activity told quite a different story. Like a radio out of tune, I couldn’t make sense of what was coming in, which led to trouble with everything from basic math to conversations to finding my way home. Damage to the parietal lobes can also result in language impairments, the inability to perceive objects normally, difficulty making things, loss of memory, and a marked change in personality. I had been a very social person before my injury, but I was now quieter and preferred to be alone, away from crowds. I would become exhausted by the smallest things, as my brain was having to work much harder to interpret all the stimuli around me. This was the new me.

My family had asked me to be honest with them about what I was going through, so that fateful day at the gas station, I thought I would let them know my true state of mind. What was most confusing about it all was that I wasn’t depressed. I would describe my thoughts at the gas station as simply “automatic,” like shutting off a light switch, tying your shoes, or putting toothpaste on a toothbrush and brushing your teeth. You don’t have to think about the steps involved in those tasks — you just do them. My brain was experiencing life-ending thoughts, and there was no real reasoning or emotion behind them. As strange as it may seem, ending my life just felt like the natural thing to do, and arriving at that conclusion was out of my control.

When I’d gone to the hospital the day of the accident, I had been diagnosed with a concussion. There wasn’t any bleeding in my brain, my skull wasn’t fractured, and the doctor said the concussion would subside in four to six weeks. As months went by, though, I began to lose cognitive abilities, such as speech comprehension and math and writing skills. That fall of 2010, I saw a specialist at a brain injury clinic who diagnosed me with a traumatic brain injury. I worked for months on relearning basic cognitive skills at the clinic, but I wasn’t getting any better. The specialist later concluded that my brain was attempting to process everything all at once, and, basically, would short-circuit as it tried to decipher the flood of input. Throughout most of 2011 and 2012, I was filling out psychological evaluations every two weeks. I was essentially on suicide watch and was heavily medicated, but the antidepressants and anti-anxiety drugs I’d been prescribed didn’t seem to help. They only subdued me. I wrestled with dangerous automatic thoughts for most of 2012.

Shortly after the incident at the gas station, I reached out to a friend who had played in the NHL and had suffered career-ending concussions. He suggested trying a treatment known as “brainwave optimization,” a form of neurofeedback that, through sensors placed on the head, identifies brainwave imbalances and transmits sounds to recalibrate the brain, eventually restoring brainwaves to a healthy balance. I began the treatment in fall 2012, and through twice-daily 90-minute sessions over five days, I at last started to feel like my former self.

One speech at a time

Concussions and brain injuries — particularly related to sports — seem to be in the news on a regular basis these days. Back in 2013, the local television station here in Victoria did a segment on my story of overcoming the challenges brought on by my injury. The TV station received numerous emails and phone calls in response to the piece, and at the end of the year, the station decided to submit the story as its entry in a national media contest. Considering how many news stories a TV station covers in a year, that mine was chosen was an honor to begin with, and you can imagine my shock when I got a call saying the station had won the national award.

Youell visits with a trio of longtime Uplands members who have also served on the club’s board of directors. Uplands has upward of 1,000 members. Photo by Chad Hipolito

The local TV coverage inspired me to start sharing my story myself in the hope of connecting with and helping others. I’d first gotten involved with Toastmasters, an educational organization focused on communication, public speaking and leadership skills, in 2001. Like many people, I had a fear of public speaking, and I wanted to boost my confidence. I gave a wide variety of speeches through Toastmasters, and even won a Toastmasters Golden Gavel Award for public speaking. I’d started doing industry presentations and teaching turfgrass management at a local community college.

Following the accident, though, all of those skills disappeared. As I tried to put my life back together, I knew I needed to get comfortable speaking with people again. Three years into my recovery, I decided to go back to my first Toastmasters meeting. On the way there, I turned the car around three different times. I called my wife, crying, saying “I just can’t do this” as I sat in my car on the side of the road. I was terrified, and I didn’t know why. My wife convinced me that taking this step was necessary to my recovery, as it would help me regain speech and comprehension skills. With her encouragement, I turned the car around once more, drove to the Toastmasters gathering, and started my public speaking journey all over again.

I’d been back with my Toastmasters club for about a year when they asked me to participate in a speech competition. I gave it a try, not thinking I would get very far. I won three competitions, each getting progressively tougher as I went up against winners from other regions, and my three wins qualified me for the finals against contestants from 320 clubs. I ended up placing third. What an amazing ride to come out of what had been an intimidating initial step and a simple desire to surmount an obstacle caused by my injury.

Close to home

For the past five years, I’ve been speaking about my injury and its aftermath at high schools, colleges and conferences, and with athletic groups. My message is simple: I was in a battle for my life and was trying to fight it alone, which is a big mistake for anyone who is dealing with adversity, be it an injury, illness, career-related setback or other type of personal hardship.

It saddens me when I’m speaking at high schools and see tears in the eyes of teenagers as they listen to my story. The tears often represent a personal connection from soccer players, rugby players, dancers and others who have sustained serious injuries. Over the years, many young people have shared their experiences with me, and I’ll hear statements like “I feel like I’m in a fog” or “I suddenly struggle in school.” Many try to hide their challenges from family and friends, much like I did. My hope has been that, after hearing my story, they’ll begin to speak up about their reality of living with the lingering effects of an accident or injury. Too often, children suffer the impacts of such trauma in silence, unsure what has happened to them.

I share my story very openly, and this candidness has led to many invitations to speak. Last year, I had the privilege of presenting at a conference in the Canadian Maritimes, and this month, I will be delivering a keynote address at Penn State University on the topic of overcoming adversity.

Another chance

I had great success with brainwave optimization treatment, and even though my brain isn’t fully back to normal, my brainwave activity now more closely resembles that of the healthy brainwave image, and I’m off all medications. There are no follow-ups with this type of treatment, and after two years with an injury like mine, there is usually no further recovery. I’ve remained quieter and more withdrawn compared with the old me, and have to push myself to step out of my comfort zone at times. I also still have some deficiencies, such as occasional confusion, anxiety, and fatigue with academic subjects. That last one pains me to admit, as I’d been working toward becoming a Certified Golf Course Superintendent in the months just before the accident. I no longer have the stamina to study, though, and I can’t seem to retain information as easily anymore, so this is unfortunately one career goal I won’t be able to achieve.

A 350-year-old Garry oak stretches toward the Uplands clubhouse from behind the 12th green. Uplands is home to the largest privately owned Garry oak stand in North America, with more than 1,000 of the trees throughout the 121-acre property. Photo courtesy of Uplands Golf Club

Despite being injured while on the golf course, leaving the golf course superintendent profession never crossed my mind. I love the people in this industry — the membership I work for, the staff I work with, and my fellow superintendents. We are a close-knit community, and the support and camaraderie are one of a kind.

In sharing my story, I’ve met more than 100 people who are also dealing with concussions or brain injuries, from as young as 6 years old to a gentleman in his late 80s. I’ll be honest — after every speech, I feel a “vulnerability hangover.” This is when you question yourself about being too honest, too revealing, and are perhaps embarrassed about your circumstances.

You may ask, then, why I do this — why do I speak? Well, a person once shared a story with me about a family of four that had been in a car accident, and the mother had suffered a serious concussion. She struggled for many months and just wasn’t herself. One day, when the family was at their summer home, she finished mowing the lawn and told her family she was going to take a walk and would be right back. She never came back. She ended her life by walking off a cliff. I have no doubt that wires were crossed and she was grappling with automatic thoughts — no rationale, no feeling, as she innocently walked away from her family.

I’m able to look back now and recognize not only how far I’ve come in my recovery, but that I’m lucky to be alive and writing this article today. After what I’ve been through, I know how strong the human spirit is. When we were younger, it seemed like we could recover so quickly — from playground injuries, from losing in sports, from hurtful friends. Yet as we get older and we don’t use our recovery “muscles” as often, we tend to doubt our ability to get through the challenging times. We are capable of doing difficult things, though, and each of us has the strength within to endure, and to recover.

I’ve come back from a place many people don’t come back from, and if I can do it, others can too. Reach out to family or friends, let them know what you’re feeling, and let them help you. Be honest with yourself. Listen to your body, and rest when you need to. Take it all one day at a time. And never, ever give up.

Brian Youell is the master superintendent at Uplands Golf Club in Victoria, British Columbia, where he has worked since 1981. He lives in Victoria with his wife, Pamela, and their daughters, Sarah and Amanda. A native of Victoria, Brian studied turfgrass management at Fairview College in Alberta and the University of Guelph, and earned a certificate in executive management from Cornell University. He is a 20-year member of GCSAA and serves on Canadian provincial and national boards of golf course superintendents.