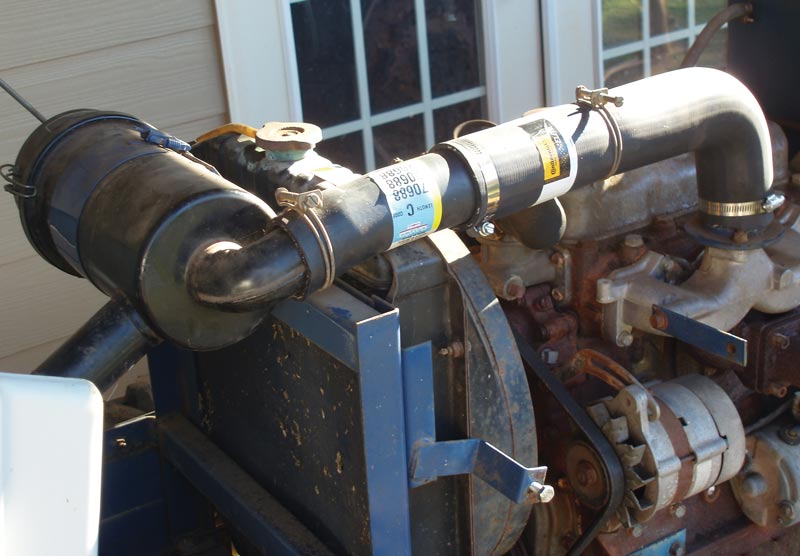

Two large-bore radiator hoses — with a steel pipe inside to reinforce the joint — formed a new intake air hose and put this 1978 Satoh tractor back in full operation. Photos by Scott R. Nesbitt

Two old diesel tractors recently lost a lot of power, and both sent smoke signals to let technicians know there were problems. Each problem was simply fixed, but each illustrated the need to remember the basic air-and-fuel simplicity of diesel engines and the need to avoid overcomplicated troubleshooting.

A 1978 Satoh Stallion S750 started blowing black exhaust smoke and wouldn’t get above 1,200 rpm. The tractor is an “orphan.” Satoh of Japan started in 1914, was absorbed into Mitsubishi in 1980, and in October 2015, the company became Mitsubishi Mahindra Agricultural Machinery Co. Ltd. There’s one U.S. Satoh parts distributor and no dealer network. But the 1.8-liter, 38-hp, three-cylinder Isuzu diesel engine had only 242 hours and had run great a month earlier pulling a 6-foot brush hog in foot-high damp grass.

Then a 1993 Kubota L2650 lost power, stumbled and stalled while brush-hogging. This tractor had under 700 hours and had always been reliable. The three-cylinder engine displaces 1.4 liters and puts out 29 horsepower.

The owners called tractor dealerships and repair shops, asking for suggestions. Both were told they might need new injection pumps or injectors, or cylinder head rebuilds. To be fair, the phone technicians couldn’t see or hear either machine, and it’s often best to prepare a potential customer for the worst. But none of the phone contacts suggested what turned out to be simple solutions.

The Satoh’s problem was lack of intake air. After 40 years, the cloth inner liner of a flex tube had collapsed, partially blocking the path from the air cleaner to the intake manifold. A new intake tube was cobbled together.

The inner liner of the air intake hose broke loose, partially blocking air to the engine and causing nasty clouds of black smoke and an inability to get above 1,200 rpm.

The Kubota’s problem was that the fuel filter had not been replaced for 25 years. A new filter cured the problem.

Diesel engines need only a lot of air and little fuel to produce power. The Satoh’s

1.8-liter engine draws in 0.9 liter of air for every full revolution (one intake stroke, one exhaust stroke). At 1,000 rpm, it needs 900 liters of air every minute. That’s about 240 gallons every minute, or 4 gallons every second. The partial blockage limited the air supply. The black smoke was unburned fuel.

A diesel’s fuel supply is regulated by a governor in the injection pump. Push the throttle to accelerate, and you stretch a spring connected to a valve called the fuel rail. The cylinders get an excess dose of fuel, which increases power and engine speed. Higher speed increases the force produced by a set of spinning weights in the fuel pump. This force pushes against the spring and moves the fuel rail to cut back fuel flow. Until the spring and weights strike a balance, excess unburned fuel shows up as black particles in the exhaust.

The Kubota’s owner had noticed the tractor’s exhaust was cleaner than normal. The fuel filter was replaced, the engine again puffed a little black smoke when accelerating, and power was back to normal. Both old tractors finished early-winter weed cleaning and seemed ready for spring.

Here are two handy troubleshooting guides for old diesels and newer emission-controlled engines, to help sort out the possible causes of black smoke and other challenges signaled by the engine exhaust and other operating problems: Diesel: Troubleshooting and Malfunction and Troubleshooting for Diesel Engine.

Scott R. Nesbitt is a freelance writer and former GCSAA staff member. He lives in Cleveland, Ga.