Examining electric: The Bear Trace at Harrison Bay in Harrison, Tenn., transitioned to electric maintenance equipment in 2013, and superintendent Paul L. Carter, CGCS, has closely monitored the move’s various effects on the facility. Shown above, the 48-volt lead-acid battery system located beneath the seat of one of the course’s Tru-Turf green rollers. Photos courtesy of Paul L. Carter

Many of you may remember the phrase “Can you hear me now?” from ads for a wireless carrier that ran a few years back. The slogan signaled that customers could be heard from almost anywhere, and while that’s a great attribute for cell phone coverage, for golf course maintenance personnel, it’s not a favorable trait. Perhaps you or your agronomy staff have gotten the “death stare” from golfers or had complaints voiced against you when noise from gasoline- or diesel-powered equipment disrupted a golfer’s round? Maybe you’ve had a hydraulic leak from a mower kill a strip of grass on your 18th green just before a tournament? Been instructed by your green committee or course owner to find a way to reduce expenses without reducing the quality conditioning of the golf course?

Well, I have a suggestion that can remedy any one or several of those issues. In March 2013, here at The Bear Trace at Harrison Bay, an 18-hole Jack Nicklaus Signature course located just outside of Chattanooga, Tenn., and known for its award-winning environmental programs, we began swapping much of our gasoline-powered maintenance equipment for 100 percent electric-powered models. This project, which we named the Electric Equipment Initiative, was funded through the Tennessee Clean Energy Grant (TCEG) in collaboration with the Tennessee Department of Environment and Conservation, through its Office of Sustainable Practices. The objective was to provide an environmentally friendly alternative to using fossil fuels to power golf course maintenance equipment — one that would save money, reduce noise pollution on the course, and lessen the carbon footprint of our operation.

Through TCEG funding, The Bear Trace at Harrison Bay purchased 18 pieces of fully electric, battery-powered maintenance equipment to replace our existing gasoline-powered units: three Jacobsen Eclipse 322 greens mowers, four Jacobsen Eclipse 322 3WD tee and approach mowers, two Tru-Turf R52 green rollers, two Smithco Super Star 48 bunker rakes, five Toro Workman MDE utility vehicles, and two Club Car Carryall 2 utility vehicles.

Money talk

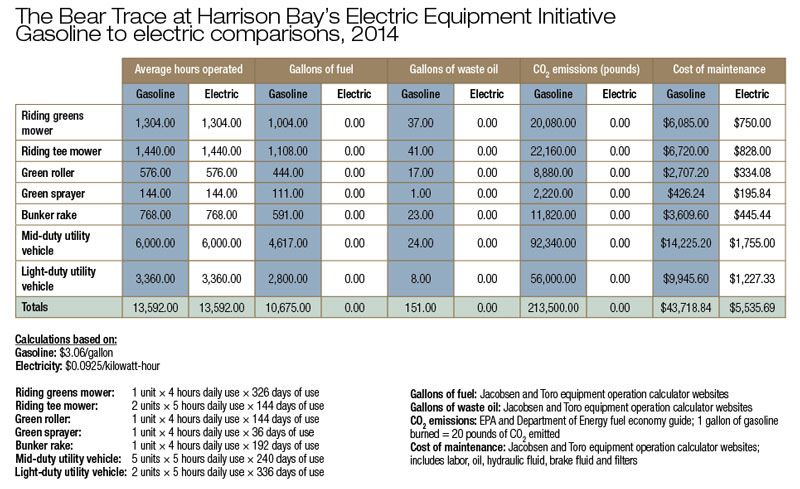

Converting from an entirely gasoline-powered fleet to an electric one reduced our fuel consumption by more than 9,000 gallons in the first year of implementation. In 2013, with oil supply limited by the spill in the Gulf of Mexico and the refinement of gasoline slowed, Chattanooga gasoline prices reached more than $3 per gallon, so this cut in our consumption saved the golf course more than $27,000 that year. (See the chart below for a detailed breakdown of the course’s gasoline vs. electric costs.)

Another perk of fully electric equipment is the lack of on-board fluids, such as engine oil, hydraulic fluid and brake fluid, along with all the filters needed to properly maintain the equipment. Eliminating the cost of these items plus the labor to maintain, replace and recycle the fluids saved our operation an additional $30,000.

Yes, electric equipment has its own maintenance expenses. Batteries must be recharged after each use, and the water levels in the batteries themselves have to be checked and topped off weekly (during times of heavy use, we check them at least twice per week). The electricity bill for our maintenance building, where the equipment is stored and charged, increased a little over $1,200 in the first year following purchasing the equipment, and that cost has remained consistent in subsequent years. On average, we use 31 gallons of distilled water per year to maintain the batteries, at a cost of $29.76.

Healthy planet, healthy people

The relationship between an agronomy staff and the tract of earth under their care is a unique one. It is, in many ways, a partnership. If the land is not healthy and prosperous, the golf course itself is unlikely to be healthy and prosperous. Superintendents are becoming more aware of this, and of how the maintenance of their golf course directly impacts the environment on and around their property. By shifting to fully electric equipment, The Bear Trace at Harrison Bay has strengthened our side of the partnership, protecting the land and water by eliminating the possibility of contamination through accidental leakage or spillage of petroleum-based products. We have also lessened our carbon footprint by reducing the transportation of fuel to the course via delivery trucks, limiting the need to store or recycle oils, and reducing exhaust emissions released into the atmosphere.

Tests have found that operating a small internal-combustion gasoline-powered engine, such as the ones typically used in greens mowers, bunker rakes and green rollers, to name a few, can produce 26 different harmful hydrocarbons. According to the EPA, air pollution from one hour of operation of one of these engines is equivalent to that of 11 new cars each being driven for an hour.

These pollutants are not only toxic to the environment, but also to the operator, who comes in close contact with the concentrated exhaust fumes on many models of equipment. Such exposure is particularly evident with equipment that requires the operator to either walk through the exhaust plume or sit in direct relation to the engine and exhaust manifold. The hazards of hydrocarbons and other emissions from small combustion engines become amplified during summer. Ozone, one of the primary pollutants that causes poor air quality during the summer months, is formed when nitrogen oxides in exhaust undergo a chemical reaction in the presence of sunlight. Ozone has been linked to several lung and respiratory issues — long-term exposure can aggravate asthma, and it’s likely one of the many causes of asthma. The risk intensifies during summer, when ground levels of ozone are already elevated.

Noise pollution

The operation of gasoline- or diesel-powered equipment is often loud, and it’s not only disruptive to golfers and the wildlife that call the course home, but has possible legal ramifications too. At many courses, maintenance must get underway before the break of dawn in preparation for daily, tournament or outing play. Beyond putting the course on unfavorable terms with nearby homeowners or resort guests, running gasoline- or diesel-powered equipment in these early hours puts an agronomy team in potential violation of local noise ordinances.

The Noise Control Act of 1972, which is the basis of many municipal noise ordinances, states that powered equipment generating in excess of 85 decibels cannot be operated before 7 a.m. and after 9 p.m. Monday through Saturday, and not before 9 a.m. on Sundays and holidays. For the majority of golf courses, waiting until 9 on a Sunday morning to begin work on the course simply isn’t feasible.

At an unveiling event for the course’s new electric equipment in May 2013, attendees — which included several Tennessee Department of Environment and Conservation staff members and state Sen. Bo Watson — had the opportunity to hop on some of the machines to experience their quiet performance firsthand.

The virtually silent operation of fully electric equipment allows a maintenance staff to perform many of its day-beginning tasks without disturbing the early-morning tranquility. Decibel meter readings I took 100 feet away from a gasoline-powered and a fully electric-powered greens mower under full operation revealed a drastic variance in the noise levels each generates, with the gasoline model hitting 83 decibels while the electric reaches 53 decibels. If your local noise ordinances are in line with the Noise Control Act, gasoline-powered equipment could put your facility at risk of legal action. What’s more, repeated exposure to loud noises or long-term exposure to decibel levels over 80 can lead to hearing loss, hypertension, anxiety, irritability, and loss of concentration or motor skills. With the operator at a heightened risk of harm, the likelihood of lawsuits and workers’ compensation claims also goes up.

The value of eliminating noise pollution wasn’t lost on the sponsors of the Electric Equipment Initiative. “Hands down, my favorite benefit of the project is the absolutely silent operation of the equipment,” says Lori Munkeboe, director of the Office of Sustainable Practices for the Tennessee Department of Environment and Conservation, which operates The Bear Trace at Harrison Bay. “With the electric equipment, our staff are able to provide excellent turf conditions while players and wildlife alike can enjoy the solitude.”

Pros and cons of plugging in

The use of electric maintenance equipment comes with more benefits than disadvantages, but nothing is perfect, and drawbacks can always be identified in most any operation. Fully electric equipment can cost a bit more initially, but it doesn’t have to. An all-electric green roller, based on MSRP, can set you back about $2,500 more than its gasoline-powered counterpart. An all-electric triplex greens mower, however, will save you close to $2,000 upfront compared with a similarly equipped gasoline-powered model, according to Mitch Parker, vice president of Ladd’s, a golf course maintenance equipment supplier in Memphis, Tenn. Additionally, the return on investment for an all-electric mower is greater than that for a gasoline-powered mower, as the savings in fuel, parts and mechanical service expenses will, over time, begin to offset any initial increase in purchase price.

Another downside to battery-powered equipment is that users have a finite amount of power to complete their tasks. It’s not as simple as adding more fuel to the machine and getting right back to work. Scheduling of daily maintenance must take into account the equipment’s battery life. Some necessary cultural practices such as verticutting just can’t be performed properly using an all-electric greens mower — not because the unit doesn’t have the capability to tackle such jobs, but because the draw on the batteries would be too great and would drain the batteries prematurely. To get around the lack of power longevity, we still rely on gasoline-powered triplexes for verticutting.

Contrast these cons, however, with the many pros of having all-electric equipment. In the case of The Bear Trace at Harrison Bay, we’ve eliminated thousands of gallons of fuel from our operation every year, which, in addition to significantly cutting expenses, has in turn eliminated point source carbon emissions, thus softening our environmental footprint, improving air quality on the course, and decreasing health risks to employees. We’ve also reined in our noise pollution to a reasonable and legal level, enhancing the well-being and on-course enjoyment of both employees and golfers.

What the future holds

For years, golf cart manufacturers have been using and improving electric technology to better serve their clients, and some golf course maintenance equipment manufacturers are now seeing the benefit in pursuing a line of fully electric equipment. The future looks to bring more-efficient electric motors, along with rechargeable solar panels that can be attached to the mowers to feed the batteries while the machines are in operation or are parked outside on a sunny day before being stored indoors overnight.

Lithium-ion-based power sources will most likely overtake lead-acid battery systems as the most economical and environmentally sound power source for electric equipment. According to George Roddan, CEO of British Columbia-based Dynamic Energy Solutions, a leader in innovative industrial alternative power sources, lithium-ion battery systems should last three to four times longer than lead-acid batteries, giving a course six to eight years of trouble-free service. And because lithium-ion batteries require no monitoring or cleaning of terminal posts or refilling of water levels, maintenance costs get trimmed. Plus, lithium-ion battery systems charge more efficiently and are about 25 to 35 percent lighter than lead-acid batteries, resulting in minimized rolling resistance, which translates to energy savings.

Electric takes charge

Darren Davis, CGCS, superintendent at Olde Florida Golf Club in Naples, Fla., and GCSAA vice president, says he has been very impressed with his fully electric green rollers. “They are quiet, quick, and have no problem rolling all of our greens on a single charge,” Davis says. “Probably the most important attribute of the units, for us, is the elimination of hydraulics on the greens.” Davis is also pleased with the “stealth mode” furnished by an electric light-duty utility vehicle, which allows him and his two assistants to travel the golf course without the worry of engine noise bothering golfers.

Use of electric equipment has made The Bear Trace at Harrison Bay a more peaceful place to work, play and live. Shown here is resident bald eagle Eloise of the famed Harrison Bay Eagle Cam, who nests behind the course’s 10th green and has had two eaglets fledge this year.

For The Bear Trace at Harrison Bay — which is one of nine golf courses along the Tennessee Golf Trail, operated by the Tennessee Department of Environment and Conservation — the Electric Equipment Initiative was so successful that the project was expanded to the other eight courses. Fully electric greens mowers are now in use on all nine. By outfitting its golf courses with fully electric equipment, the Tennessee Golf Trail has the potential to eliminate the use of more than 15,000 gallons of fuel each year, reduce point source carbon emissions by more than 215,000 pounds, and slash course maintenance expenses by more than $52,000 annually.

Greens must be mowed, bunkers must be raked, and staff and equipment need to be ferried about the golf course. Tackling these essential tasks with electric equipment can equal savings for your operation on many fronts, and provide a more peaceful and enjoyable course for golfers to play and wildlife to inhabit.

Paul L. Carter, CGCS, is the golf course superintendent at The Bear Trace at Harrison Bay in Harrison, Tenn. A 25-year association member, Paul has won several environmental stewardship awards, including the Environmental Leaders in Golf Awards top honor in 2013, and GCSAA’s President’s Award for Environmental Stewardship in 2015. He lives in Ooltewah, Tenn., with his wife, Melissa, and daughter, Hannah.