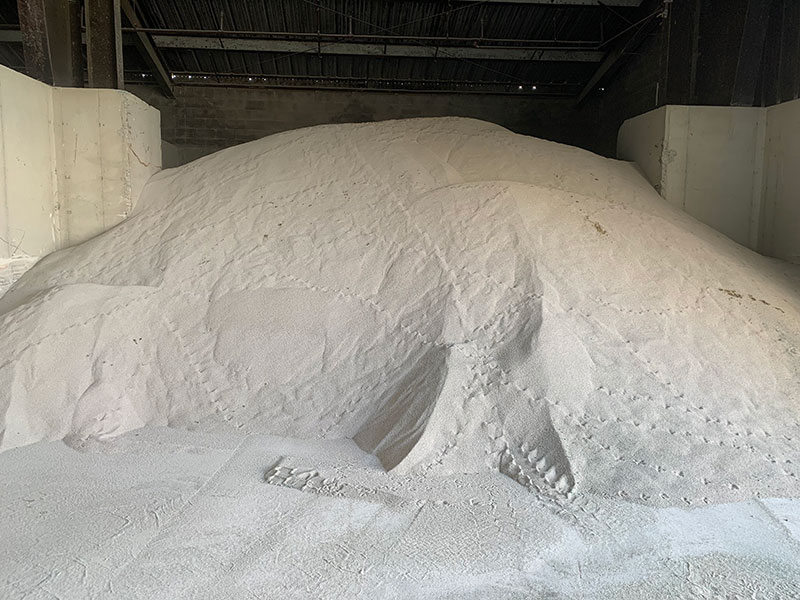

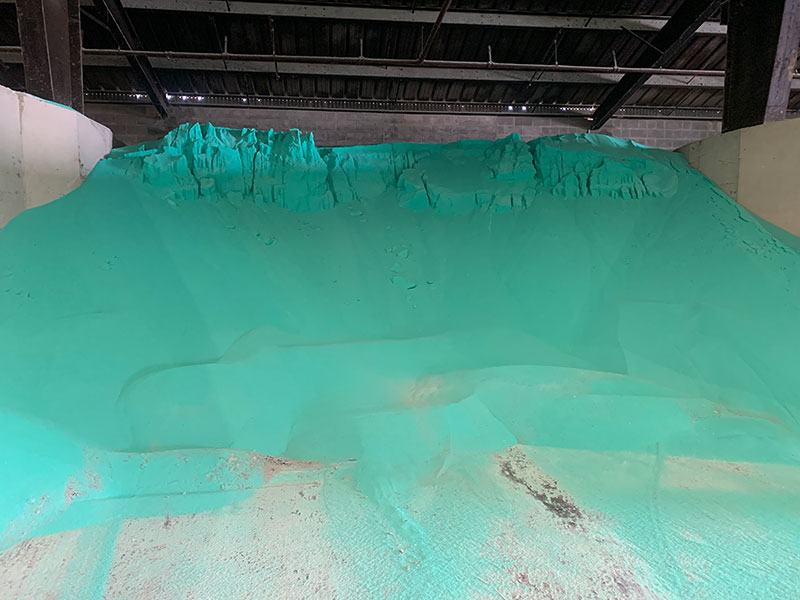

Pallets of fertilizer await order and delivery at LebanonTurf. Photo by Chris Gray

The price of natural gas in Europe jumps, Russia declares war on Ukraine, and a golf course superintendent in middle America wonders if he’ll have to cut back on how many labor hours he can allocate to trim around bunkers.

Talk about a butterfly effect.

In the seeming never-ending run of bad financial luck befalling superintendents — like inflation, fuel costs, supply-chain issues, crippling labor shortages, and who can forget the Great Grass Seed Shortage of 2021 (and beyond)? — few misfortunes are as potentially budget-bending as the skyrocketing cost of fertilizer.

“I’ve been a superintendent since 2008, and I’ve never seen prices as high as they are,” says Grant Backus, GCSAA Class A superintendent at Shipyard Golf Club in Hilton Head Island, S.C., and a 17-year association member. “With

inflation and everything else ... it’s tough.”

And while the butterfly effect — the metaphorical notion that an insect’s beating wings on one side of the earth can lead to a tornado on the other — is at play here, one longtime fertilizer follower leans more toward another winged

motif to explain the roiling realm of fertilizer. Josh Linville, director of fertilizer for financial services network StoneX and a 20-year veteran of the traditionally less volatile fertilizer market, has taken to tweeting with the hashtag #blackswan,

indicating the forces at play driving up the cost of all things N-P-K are a once-in-a-lifetime culmination of factors, or a so-called black swan event.

“It’s a match,” Linville says, “made in hell.”

‘It was a slow build’

The first inkling there were fell fertilizer influences afoot might have come a year ago.

“There are so many things that happened that led to it,” says Chris Gray, golf channel manager for LebanonTurf, a 22-year GCSAA member and a former superintendent of 18 years. “It was a slow build that just continues to get worse.

“There were natural disasters, wildfires in California, then the lovely stuff happening in Europe had a much more direct impact. All these things were compounding on one another. We were seeing increases happen 12 months ago. Urea started to rise.

That’s one indicator. Clearly, we’ve seen all these increases show up in nitrogen, potash, phosphate. The increases started happening a year ago. That’s the starting point. Then it started snowballing.”

Stockpiles of, from top, urea, methylene urea and muriate of potash, or MOP, at LebanonTurf. Photos by Chris Gray

The underlying explanation, of course, is the Econ 101 staple of supply and demand. But convoluted monkeying with both sides of that equation did more than simply nudge the needle. Before long, that needle — and heads — were spinning cartoonishly.

“We look every week (at fertilizer costs),” Gray says. “In a normal year, we produce one price sheet in the fall. I’ve been here 10 years, and fertilizer is the only price sheet we would issue only once a year. The market just

never fluctuates. This year, we’ve priced five times. That’s how much things are changing out there on a constant basis.”

Even without market-specific influences, fertilizer likely would have cost more in 2022 than, say, 2020, when the Big Three of turfgrass macronutrients (nitrogen, phosphorus and potassium; or, more accurately, the components that go into the products

that provide those nutrients) were at or near historic lows. Inflation, fuel and freight costs and other weak links in the supply chain were destined to goose prices. But a perfect storm was building.

Gray says urea is the primary driver of cost associated with a bag of fertilizer, and that market is a mess. A surge in demand for urea at the start of 2021 started the climb, but that was only the beginning. European natural gas prices, driven by pandemic-recovery

demand, rose more than 340% in 2021. That matters, because natural gas makes up 75% to 90% of all operating costs for the production of synthetic urea. When natural gas prices jumped, “countless” fertilizer factories closed, Gray says,

because they were unable to absorb the increased manufacturing costs, which immediately triggered a urea shortage, which led to near-record pricing.

Hurricane Ida hammered the U.S. Gulf Coast in August 2021, constricting the flow of goods to and from the U.S. (New Orleans is a crucial port for the import of fertilizer components) and shutting down all the ammonia plants in the area, thus restricting

the availability of urea nitrogen even further.

Then Russia — which, Linville says, produces 14% of the global urea supply (and 25% to 31% of the global urea ammonium nitrate supply) by itself — invaded Ukraine. Resultant sanctions against Russia and partner-in-crime Belarus essentially

took or will take their contributions of those components out of the equation. Germany suspended approval of the Nord Stream 2 natural gas pipeline, striking a blow to Russia but imperiling Europe’s supply, and Russia, which supplies 40% of

Europe’s natural gas and 25% of its oil, pushed back, recently refusing to supply Poland and Bulgaria with natural gas.

All these current events drove up prices just as natural gas costs were starting to stabilize in the area, further endangering urea production.

But that’s not all.

China essentially banned the export of urea and phosphate to ensure its needs are met, and ongoing pandemic shutdowns in that country have caused snarls across the supply chain, including with some of fertilizers’ raw materials, like urea-formaldehyde

(UF) concentrate, the vast majority of which goes into the production of adhesives and wood products, like particle board, plywood and medium-density fiberboard (MDF).

“The wood industry bought up all it could, which drove up the components we use to make methylene urea,” Gray says. “Most people have no clue about the raw materials. Coated urea ... those coatings come from China. N, P and K are just

one part. UF concentrate costs are up 200%. How do you explain that to somebody? There are a lot of unseen costs — so many aspects people aren’t aware of.”

What about ‘Mother Ag’?

And that’s not even considering the role of agriculture. “Mother Ag,” as Gray refers to her, buys up 90% of the United States’ allotment of urea, leaving turf and ornamentals and all other channels scrambling for table scraps. Traditionally,

when nitrogen prices spike, U.S. farmers respond by swapping out acres dedicated to nitrogen-thirsty corn for soybeans, which can convert atmospheric nitrogen into ammonia to meet much of their N needs. But high corn prices — coupled with high

costs for phosphorous and potassium that soybeans require, thus offsetting potential savings from nitrogen — mean it makes more financial sense for farmers to continue to put in corn.

“We’re a minor player in the fertilizer commodities market,” Gray says. “Ag directs everything. As the thirst for corn continues to grow, the millions of acres of corn planted has impacted how much is available to us. Because the

phosphorous and potash markets are accelerating at the same rate as urea, there’s no viable reason to switch crops. Corn continues to drive what’s needed for food production, and while we love grass, people need to be fed. There’s

little left for us.”

Just as the urea market is roiled by several interwoven factors, myriad movers have conspired against the other three legs of the holy N-P-K triumvirate. Remember the sanctions on Russia and Belarus? Russia contributes 10% of the global phosphate total

and 20% of the world’s potash supply. Belarus produces 18% of global potash.

European natural gas prices and the shutdown of the massive Mosaic potash mine in summer 2021 in Canada also stymied the U.S. availability of fertilizer.

Whew.

“So, there are a lot of problems going on with this,” Gray says. “There are so many issues going into it, there’s no simple solution.”

Rolling with the punches

What’s the bottom line for a fertilizer-dependent golf course superintendent?

Again, there’s no simple solution. But there’s no question superintendents universally are and will continue to feel the pinch.

According to GCSAA’s 2021 Maintenance Budget Survey, fertilizer was the second biggest golf course maintenance expense nationally at just over 5% for 2020. Labor far and away was No. 1, at 56.74%. It’s worth noting, though, that because the

cost of water is so varied, it is not included in the list of largest maintenance expenses; overall nationally, that line item is nearly 13% of the total budget among golf courses that purchase water.

Fertilizer expenses are also somewhat regional. In the Southeast, fertilizer costs made up nearly 7% of maintenance budgets in 2020. Courses in the Pacific region, in contrast, spent just 3.5% of their maintenance budgets on fertilizer in 2020.

“Before, we were talking about fertilizer being 6½% of the average budget, and now it’s probably closer to 10%,” Gray says. “You have to be able to respond to that. They don’t want to raise the budget, so you have

to play the shell game. A lot of courses will have to make hard decisions. Do you want to cut the fertilizer budget? You don’t want to make decisions that will have a detrimental effect on turf. It’s not like you can go without fertilizer.

Right: Superintendent Jody Shahan puts out an early morning application of methylene urea at Adams Municipal Golf Course in Bartlesville, Okla. Photo by Jody Shahan

“One, you can trade down to a less sophisticated fertilizer. There are numerous types out there. But superintendents become comfortable with what a product gives them. If that’s now out of your price range, trading down is an option, but

what effect will that have on the quality of turf? That’s a dangerous game to play.

“There are other things you can do,” Gray says. “You can cut down areas you maintain — out-of-play areas, naturalized areas. An overall reduction in maintained areas cuts down on inputs and labor. There are some tricks like

that. Superintendents are well versed in areas they can cut. What about pesticides, weed control, fungicides? You can’t stop putting down dollar spot treatment on greens. In some cases, there might be no effect at all. Membership has certain

expectations for conditions, so, ‘Here’s the money.’ I think it will impact those mid-tier courses and lower, the mom-and-pops, who are depending on those revenues to maintain their course. If they can’t afford to maintain

the course to expectations, when you hit that tipping point that people stop coming to your golf course because of conditions, it’s a domino effect. Every course is different in how they will decide to deal with it.”

Tales from the trenches

Sea Palms Golf & Tennis Resort in Saint Simons Island, Ga., where superintendent Justin Collett is spoon-feeding in an effort to curtail fertilizer usage. Photo by Justin Collett

Justin Collett, director of agronomy at Sea Palms Golf & Tennis Resort in Saint Simons Island, Ga., says he has seen across-the-board increases in fertilizer costs.

“Some of the stuff I buy used to be $17 a bag. It’s up to $23 a bag now,” he says. “Granular has more than doubled in price.”

Rather than broadcasting granulars, he has switched to spoon-feeding.

“It’s looking like we might be in this for the long haul,” says Collett, a nine-year GCSAA member. “That makes it a little scarier. And availability is an issue. I tried to order two pallets today. They only had one. Stuff

we used to get right away now takes two weeks or more.”

Over at Shipyard GC on Hilton Head Island, Backus, too, has turned to spoon-feeding as an alternative to slow-release N that has more than doubled in cost.

“You’re not getting that big slug up front,” he says, “but you can spray a little bit frequently and manage it that way.”

He also put out an application of 5-3-0 sludge — prilled human waste. “The price of that stuff,” he says, “has barely moved.”

At Deer Creek Golf & RV Resort in Davenport, Fla., GCSAA Class A superintendent Ryan Herren, a 24-year association member, has seen about a 40% increase in fertilizer costs. He’s experimenting by increasing the amount of his slow-release

nitrogen in hopes he can cut out one application.

“You gotta change things,” he says. “We’re putting it down a little heavier and hoping we can skip an application. It’s still too early to see if it’s going to hurt us.”

A busy day on the practice green at Adams Municipal GC in Bartlesville, Okla. Photo by Jody Shahan

Half a continent away, in Bartlesville, Okla., Jody Shahan hasn’t felt the pinch — yet. After consulting with sales reps last summer, he anticipated a big jump in costs for all his chemicals and had the foresight to stock up.

“By the time I hit fall of last year, I had everything I needed for the 2022 growing season sitting in my shop,” says Shahan, superintendent at Adams Municipal Golf Course and a 16-year association member. “I’m hitting the

tail end of my budget year now, and I’m a lot broker now than I’d normally be, but that’s because I bought a season and a half of the same chemicals in the same budget year. I thought it was a gamble worth taking. I’ve

had reps come see me now who say, ‘You probably made one of the smartest moves you could make.’ I went to the city manager and said, ‘I’m broke right now.’ He was, like, ‘You did a good thing. If you have budget

concerns down the road, we’ll address them then.”

Granular fertilizer alone consumed close to 10% of his $50,000 annual chemical budget. The thought of that doubling — or worse — is concerning.

“Honestly, I was more concerned about availability than I was pricing,” Shahan says. “There’s not much you can do on pricing. When the stuff was available last fall, I jumped on it. You couldn’t even walk in the chemical

room when the stuff came in.”

He’s wrapping up work on next year’s budget and increased his chemical budget by 25%. “I’m hoping that’ll do it,” he says.

If not?

“Then we’ll have to start looking at things,” he says. “We might have to look at maybe fertilizing just the short grass, not everything. Obviously, greens have to stay where they are. My bermuda is what would suffer. I’ve

definitely heard people talking about it. Some people are talking about cutting manhours instead to make up for it. There are courses talking about edging bunkers twice a year to save manhours. That money has to come from somewhere. You can cut

back in ways like that because you can’t let the grass suffer.

“Another option for us is to change up the preemergent on our bermudagrass. I spray Spectacle in the fall, and I try to go deep in the roughs with that. Maybe we scooch in a little, maybe use something cheaper when we start hitting tall grass.

That’s how I’ve had to deal with stuff in the past. Once you hit the tree line, it’s going to be getting the cheapest preemergent on it, and it’s not going to get fertilizer.”

Chris Rice, GCSAA Class A superintendent at Salina (Kan.) Country Club and a 14-year association member, also benefited from early-ordering his fertilizer.

“I heard some things would be hard to get because of shipping and COVID and all that, so I early-ordered a lot more. I usually don’t early-order fertilizer, but I did last year,” says Rice, who still noticed a 15% increase in his

fertilizer prices as far back as October 2021.

In the run-up to the Senior LPGA Championship that Salina CC will host in July, Rice anticipates he might have to make an early-season fertilizer order to combat some winter desiccation on his greens. He’s bracing for sticker shock.

“You just might have to cut other places,” he says. “With fertilizer and stuff like that with grass, you don’t have many options. Fertilizer and fuel ... you have to have it. You can’t just stop using it because you don’t

want to pay more.”

Andrew Hartsock is GCM’s senior managing editor.