Gary Player is deep in legend territory as one of only five professional men’s golfers who have won the career grand slam. He has also hit a home run with his philanthropic work, a philosophy that was shaped long before his star ascended to the elite level. Photo by Christian Petersen/Getty Images

Gary Player knows his way around a maintenance building.

Near the second hole of The ACE Club in Lafayette Hill, Pa., Player would enter the 20-by-20-foot office of John Canavan, CGCS, take a seat, remove his dress shoes and put on his work boots.

“He treated everyone he encountered on our crew as if they were the most important person,” says Canavan, a 36-year GCSAA member who has special, vivid memories of working side by side with Player on one of Player’s signature designs some two decades ago. “His commitment to the environment goes hand in hand with our profession. He’s such an ambassador for the game.”

The master list of golf icons surely has Player featured prominently. A native of Johannesburg, South Africa, Player is one of only five men who have completed the career grand slam. The others are Gene Sarazen, Ben Hogan, Jack Nicklaus and Tiger Woods.

Known as “The Black Knight,” Player dressed in black long before Woods wore red. Player was skilled with a 4-wood and at manhandling bunkers and producing red numbers on leaderboards. He has written books and authored 165 triumphs on the course, including nine major championships on both the regular and senior tours, spanning seven decades. Player’s unselfishness to buoy others through his charity — illustrated through donations of several million dollars and counting — doesn’t seem to have an expiration date.

Among the early examples of his generosity is the paycheck he earned for winning the 1965 U.S. Open at Bellerive Country Club in St. Louis, which completed the career grand slam. Player donated $20,000 from that momentous victory to promote junior golf and $5,000 to a cancer research fund.

A noted fitness fiend, Player unsurprisingly helped shape fellow South African Ernie Els.

“From a young age, my dream was always to win majors and try to emulate Gary Player. He’s a true legend of the game, and I feel privileged to call him a friend,” Els says. “He’s been an inspiration and role model to thousands of golfers, me included. I think his attitude embodies everything that matters in golf and in life.”

Now, Player and Els have more in common than sharing a native homeland. Player is the 2020 recipient of GCSAA’s Old Tom Morris Award, an award Els received in 2018. They are on a list of winners that includes Arnold Palmer, Annika Sorenstam, Paul R. Latshaw, Pete Dye and Bob Hope.

In 2002, Player (center) worked closely with John Canavan, CGCS, (left) and one of Player’s designers, Warren Henderson. They were in the process of building The ACE Club in Lafayette Hill, Pa. Photo courtesy of John Canavan

Presented annually by GCSAA since 1983, the Old Tom Morris Award goes to an individual or group of individuals, who, through a lifetime commitment to the game of golf, has helped to mold the welfare of the game in a manner and style exemplified by Old Tom Morris, a longtime superintendent at St. Andrews and a four-time Open Championship winner. Player will be honored Jan. 29 during the Opening Session of the 2020 Golf Industry Show in Orlando.

“I have tremendous respect for all the fellas and ladies and all the staff that get up early in the morning and prepare a golf course for members,” says Player, 84. “They do an incredible job.”

So does Player — in numerous ways, says GCSAA President Rafael Barajas, CGCS. “Gary Player’s legacy in golf is known worldwide, but he should be equally recognized for his philanthropic endeavors through The Player Foundation,” Barajas says. “We are truly honored to bestow the Old Tom Morris Award on a consummate gentleman who has worked tirelessly for underprivileged children and impoverished communities around the globe. Gary Player embodies not only the best of golf, but the best of humanity.”

Benevolent beginnings

It isn’t every day that somebody hands you $56.6 million. When Player and some of his famous friends — including Lee Trevino and Dan Marino — are involved, moments like this are more than just a dream.

Although it happened more than a year ago, Mountain Mission School President and Chief Financial Officer Chris Mitchell remains in awe of that day when he was presented with the hefty check. It was the product of the American Legends for Mountain Mission Kids, an all-star charity golf event at The Olde Farm in Bristol, Va., which, according to the PGA Tour, was the largest single-day charitable event in Tour history.

Player, who launched The Player Foundation in 1983 to help fund charities and drive the betterment of impoverished communities and the expansion of educational opportunities worldwide, was front and center at that event. Mountain Mission School is just one of many initiatives The Player Foundation supports or has launched. The 98-year-old school is located in Grundy, Va., and its mission is “to stand as a refuge, resource and relief” for more than 200 children who receive residential care, shelter, clothing, nutritious meals and education annually.

Blair Atholl School in Player’s native Johannesburg has a special place in his heart, including the pre-primary school. His efforts in 1983 to establish the school was an opportunity for Player to provide quality education to less-fortunate children living in rural areas. Photo courtesy of Gary Player

Mitchell can imagine what a world would look like if others patterned themselves after Player. “He has been good to us. He has a great heart and a drive to help others,” he says. “His heart overflows with generosity. He’s about just doing good, and it seems he has taken a biblical stand of doing good. If all of us took that stand, the world would be a better place.”

To trace when and why Player decided he was going to make a difference, 1957 is as good a place as any to start. With $250 in his wallet and a pocketful of maturity, Player arrived that year in America. He was just 21, but what he left behind forced him to grow up much sooner.

At the age of 8, during World War II, Player’s mother, Muriel, died of cancer. His father, Harry, toiled 8,000 feet or more underground, working long hours in gold mines. His sister, Wilma, attended boarding school. His brother, Ian, went to fight in the war with the Allies. That left Player practically to raise himself.

“I had to travel an hour and a half to school and an hour and a half home. I’d get home, and there’s nobody there, and I’d cook my own food and iron my own clothes, and I’d lie in bed crying, wishing I was dead,” Player says.

He eventually transformed that despair into the motivation that has benefited so many others around the planet. “That was the greatest gift bestowed upon me because it taught me to fight adversity,” he says. “So I said, ‘When I’m a champion one day, I’m going to help people that are struggling.’ And we’ve helped tens of thousands of people all around the world with difficulties and improved their lives.”

Right: Player’s third and final green jacket at the Masters came at age 42 in 1978. Defending champion Tom Watson (left) places the jacket on Player. Watson finished one stroke behind after Player dazzled down the stretch, firing a final-round 64 at Augusta National Golf Club. Photo courtesy of Gary Player

The Player Foundation began to make its impact 36 years ago, establishing the Blair Atholl School in Johannesburg, a facility that offers its students meals, education, recreational opportunities, and medical and dental care. In 2005, the foundation began supporting Pleasant City Elementary School, which is located in a part of West Palm Beach, Fla., known for high rates of crime and drug use. The foundation’s goal was to offer a safe haven and quality education for children there. In China, the Gary Player Classic presented in partnership with Coca-Cola benefited those affected by AIDS.

In October, GlenArbor Golf Club in Bedford Hills, N.Y., hosted the Berenberg Gary Player Invitational for charity. It’s just another example of an icon on a mission.

“He’s the most respectful, thoughtful, outgoing, vibrant personality of anyone you’ve ever met,” GlenArbor President Morgan Gregory says. “Members would walk by, and he would say, ‘Hey, would you like a putting lesson?’ That’s just him, fully engaged, 100 percent of the time. It’s no act. The more you’re around him, he becomes infectious. You want to hang around him.”

Michele Throssell has been in his presence since her birth. Player is her father — and so much more. “I respect him simply because of the man he is — loving, caring and great fun to be around,” Throssell says. “He continues to inspire me and all those around him with his love, kindness, determination and passion for life. I’m still in awe of his achievements, his dedication to the game of golf and his commitment to every single person he comes in contact with. This award epitomizes everything he stands for.”

Greatest ‘Player’ ever?

Jack Nicklaus has notched more major championships than anyone, with 18 titles on the regular tour. That isn’t enough evidence, though, for him to rank himself as the top player in history.

His No. 1 choice? Player.

“He’s not only had a fantastic golf career; I’d say pound for pound, he’s probably the best golfer that ever played the game,” Nicklaus says.

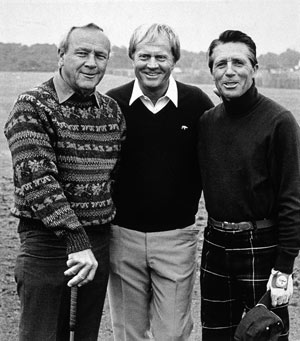

Right: Three giants of the game, (from left) Arnold Palmer, Jack Nicklaus and Player. Photo courtesy of Gary Player

Player’s name carried little weight at the start of his career, but not because of his slight 5-foot-7-inch, 150-pound frame. Player was too poor to afford a hotel room, so instead, he slept on beach dunes. Player posted his first victory in 1955 in the Egyptian Matchplay. He won for the first time on the PGA Tour at the 1958 Kentucky Derby Open at Seneca Golf Course in Louisville, finishing 14-under-par to beat Chick Harbert and Ernie Vossler each by three strokes.

His major breakthrough happened in 1959 when Player won the Open Championship at Muirfield Golf Links in Scotland. It was his first of three Open titles. His 1961 victory at the Masters was one for the record books as it made him the first international golfer to prevail at Augusta National Golf Club. He won there twice more, including as a 42-year-old in 1978. Leaning on his eternal-optimist ways, Player defied age and the odds that year, rallying from seven shots back with a final-round 8-under 64. That round featured a 15-footer for birdie on the 72nd hole to defeat defending champion Tom Watson and two others by one stroke.

“I think the mind is the key in majors. The mind is the most important thing in golf,” says Player, who also won two PGA Championships among his major haul and, at age 62 in 1998, became the oldest golfer to make the cut at the Masters. “I get so tired hearing about long hitters. That’s all everybody talks about. That’s not the answer. It’s the mind. And how well you putt.”

Fellow player Jim Colbert thinks there’s more to it than that in evaluating Player’s success.

“He didn’t have Jack’s (Nicklaus) power. Gary had average driving distance. He was very good with the lead,” says Colbert, who along with several friends visited Player in South Africa about 10 years ago. Player picked them up in a school bus and took them to his ranch, where his barn was stocked with yearlings and a phonograph that was used to play a record of “The Star-Spangled Banner” after they arrived.

“I would say Gary maxed out his mental and physical capabilities,” Colbert says. “Mentally tough and focused. Nothing fazes him.”

The most valuable person in his career, Player says, is his wife of 62 years, Vivienne. The father of six, Player counts Vivienne as a perfect 10. “Think what my wife had to put up with, with me traveling back and forth, across the world (he’s flown more than 16 million miles),” says Player, who was part of the first induction class for the World Golf Hall of Fame in 1974. “I had an opportunity (to live in the U.S.), but didn’t. Had I lived there, I know I would have won more majors than I have now because traveling all that way all the time is very difficult.”

Singing the praises of superintendents

If somebody asks Player to provide thoughtful insight on superintendents, he’s ready.

“I say to people, ‘Can you imagine in your little garden, which is a quarter of an acre and how hard it is to keep in good shape ... and these folks (superintendents) keep 200 acres in shape?’ It’s not easy because climate has a lot to do with it. Rain, no rain. Locusts. Worms. You could go on and on and say what difficulties they have to work under. And the results they get are remarkable,” Player says.

Thracian Cliffs Golf & Beach Resort in Bulgaria is one of hundreds of golf courses designed by Player. The 18-hole signature design offers stunning, scenic views of the Black Sea coast. Photo courtesy of Gary Player

A designer of more than 400 courses worldwide, Player insists all he oversaw have a common thread.

“Without the superintendents and greenkeepers and their staffs, you could never have your name as a designer be put forward with any authenticity, vision and praise. We design the golf course. But they polish the diamond. We give them the diamond, and they polish it,” Player says. “Not only that, but they also make golf so enjoyable for all their members, and it’s one of the most ungrateful jobs, because to try to please all your members is absolutely impossible. But I can tell you, I know these superintendents — male or female — are up early when everybody else is sleeping, and they do their utmost.”

Todd Bohn, the GCSAA Class A director of agronomy at Big Cedar Lodge in Hollister, Mo., has spent time with Player, who designed the 13-hole short course, Mountain Top, at the resort near Table Rock Lake. Player’s involvement is anything but tepid, Bohn says.

“He’s very in-tune with what the superintendent does in playability aspects of the turf and how the ball reacts to turf conditions,” says Bohn, a 20-year association member. “He wants to make sure the ball comes to rest and make it so it doesn’t kill the average player. He asks a lot of questions and is thorough. When he’s here, he’s high-energy, full of life, keeps everybody loose.”

Canavan had similar experiences at The ACE Club. “His energy level is contagious,” he says. “He paid attention to every little detail on the course. You could tell why he’s a (career) grand slam winner. His observations were really deep. He was focused on what the membership wanted, not so much what Gary Player wanted.”

His legacy

At his home in Plettenberg Bay, South Africa (he also has a residence in Florida), Player enjoys sharing his digs with his 17 horses. His stud farm has bred more than 2,000 horse racing winners. Horses have had a special place in his heart for a while. “After mom died, a friend invited me to his farm, and we would ride horses. I loved it so much,” Player says. “I’ve come to love my horses as much as I love golf.”

And he’s still got game. “I shot 16-under my age the other day,” Player says. “My big dream is to beat my age by 18 shots.”

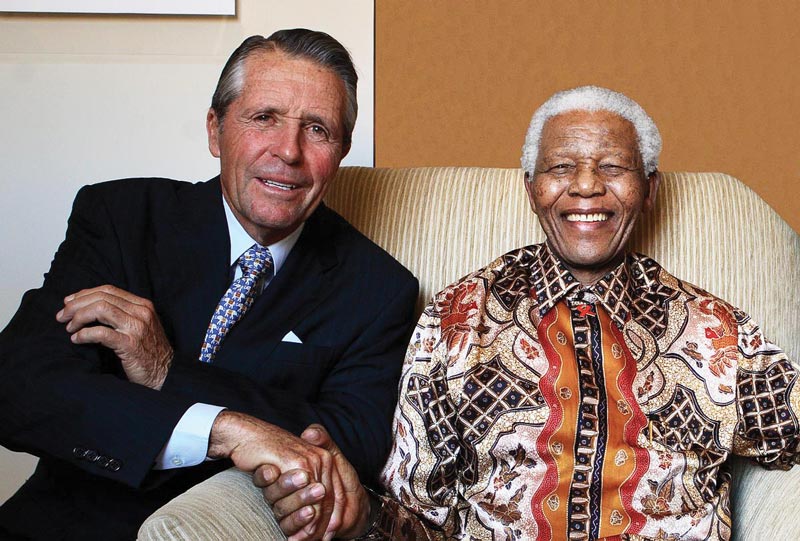

South African leader Nelson Mandela (right) thought highly of Player for making a stand for his fellow South Africans. Photo courtesy of Gary Player

And, yes, he remains as steadfast as ever when it comes to exercise and proper diet. Before muscled Brooks Koepka was even born, Player and fellow pro Frank Stranahan were at the forefront of introducing weight training and exercise programs in golf. Player’s strict and high-intensity exercise regimen is a staple of his life. “We (he and Stranahan) were ridiculed and teased,” Player says. “My brother asked me when I was young what I wanted to be, and I said a sportsman. He said I was too small, but he bought me some secondhand weights. We didn’t have gymnasiums and fitness trucks on tour. I used the YMCA. Wonderful organization.

“The human being is supposed to live to 100. Exercise, eat properly, learn to laugh more and enjoy life and nature and sleep and rest well. I’ll settle for 100.”

Nelson Mandela, the late South African president and famed leader of the country’s anti-apartheid movement, once said Player contributed to the betterment of his fellow countrymen as much as anyone by standing up for their rights. And even though Player isn’t overly concerned with how he’ll be remembered, what he has accomplished for himself and mankind will be hard to forget.

“I don’t want a big fuss made about me because everybody forgets you. Doesn’t matter who it is,” says Player, whose tributes besides the Old Tom Morris Award include the PGA Tour’s Lifetime Achievement Award, its Payne Stewart Award and the USGA’s Bob Jones Award. “I don’t believe in legacies. I do believe you’re here to do a good job while you’re here and make room for others to take over. All I’d like is to be remembered as a man who tried to contribute to society.”

5 questions for Gary Player

Q: You’re known for wearing black. What initiated that as part of your wardrobe?

A: My father once told me to have a trademark, a distinct look. I got the idea (to wear black) from a TV western (“Have Gun — Will Travel,” which aired from 1957 to 1963). He (actor Richard Boone, who played the show’s main character, Paladin) was a mercenary for hire to solve others’ issues. He’d say, “I can help you. Here’s my card.” He was fantastic.

Q: What does it mean to be only one of five men to win the career grand slam?

A: You know, I’d be wrong if I claimed I did it all on my own. It’s a blessing from above — a divine gift.

Q: It seemed Tiger Woods was well on his way to challenging the record of 18 major championships belonging to Jack Nicklaus before issues plagued him for more than a decade. What do you think of Tiger nowadays?

A: Tiger won the U.S. Open (in 2000) by 15 shots. Not five. Fifteen. There’s no question he would have gone on and won at least 20 majors, not even a doubt in my mind. He had some difficulties he encountered, which was unfortunate for his career. The comeback he made at Augusta (to win this year’s Masters, his first major title since 2008 and 15th of his career) had us all in tears because he had so much adversity in his life, on and off the golf course. I take my hat off to him, and I hope he can win another major or two.

Q: Maintaining health is extremely important to you. Why?

A: If you’re talking about a good car, it’s not a good car if it lasts you three years. I wanted to show people by exercising and eating properly and adhering to a lot of other principles that lend themselves to longer life spans that they would see me as a good example and listen to me.

Q: What is your favorite breakfast?

A: A glass of green juice. It includes cabbage, spinach, broccoli, cucumber, carrots, and then put in an apple to sweeten it up. I tell you, it’s like magic!

The king and I

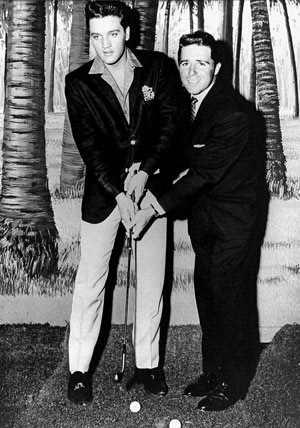

The late golf great Arnold Palmer was known as The King. He wasn’t the only famous King, however, with whom Gary Player crossed paths.

Another King — Elvis Presley — initiated contact with Player. It happened following Player’s appearance on a morning TV show during which he played a guitar and tried to impersonate Presley. Apparently, Presley was intrigued by Player, who was coming off of his first Masters championship in 1961.

“I got a telegram from him saying, ‘I’d like to meet you.’ I responded, ‘I’d like to meet you too, King,’” Player says. He went to Los Angeles to visit the set where Presley was in production for his movie “Blue Hawaii.”

“I walk in, and he says, ‘Cut.’ He stopped everything, put on his jacket. He got a golf club and showed me his grip. Terrible grip. It looked like a cow giving birth to a roll of barbed wire,” Player says. “So I get his grip right. Then he says, ‘What else is important?’ I said, ‘You’ve got to get your hips right.’ He said, ‘Baby, you’re talking to the right man.’ And, man, did he give me some hip action.” Presley was famous for his on-stage performance during which his hip movement and gyrations drove many of his fans into hysterics.

Presley died in 1977 at 42. He passed away at half of what is Player’s current age. “What a tragedy. I liked him so much, and what a shame he died at that age, so young,” Player says.

Howard Richman is GCM’s associate editor.