A drone’s-eye view of research plots established by Michelle Wisdom at the University of Arkansas Agricultural Research and Extension Center in Fayetteville, Ark., for her graduate work on pollinator-friendly plants. Photo by Daniel O’Brien

When you look at your golf course, what do you see? Or, maybe a better question is, what are you not able to see that you wish you could? What images, what visuals, would help you do your job more effectively and efficiently? If you were able to see more of your course on a daily basis, what would that do for turfgrass quality and crew management?

Here we’re talking about the essence of scouting, a practice as fundamental to greenkeeping as any there is. And there’s an important point to make here at the onset, one that’s often overlooked if not altogether misunderstood: Technology is not about replacing long-standing, tried-and-true practices; it’s about enhancing them.

Good technology allows a golf course superintendent to see more and ultimately do more. If there were an opportunity to increase how much of your course you’re able to put your eyes on every day, how interested would you be in that technology? It’s out there now in the form of unmanned aerial vehicles, also known as drones.

I feel the need — the need for ... government bureaucracy

Of course, we all recall the iconic “Top Gun” scene on the aircraft carrier when Goose and Maverick are told they’re heading to Top Gun — and are promptly handed a fat stack of FAA manuals to study. No. No way! Nothing takes the sexiness out of flying quite like federal regulations, but let’s just go ahead and get this bit out of the way now.

The take-home message here is that if you’re operating a drone in U.S. airspace, you’re doing so under the authority of the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA), and you need to (1) register the drone with the FAA, and (2) obtain an operator’s license from that agency (in order to fly for anything other than purely recreational purposes). For both tasks, this section of the FAA website is a great starting point. Registering your drone is as simple as providing some basic info and paying a small fee. Acquiring the remote pilot’s license involves registering for and passing a certification exam. The license is good for two years.

UAVs: Fixed-wing or multi-rotor

Unmanned aerial vehicles (UAV) or unmanned aerial systems (UAS) come in a variety of shapes, sizes and price tags. Essentially, all UAVs can be classified as either fixed-wing (planes) or multi-rotors (helicopters). Although fixed-wing aircraft offer certain advantages in terms of wind stability and long-distance flying, for most golf courses, multi-rotors are a better option because of their maneuverability — including hovering capability and their ability to take off and land in relatively tight spaces.

Editor’s note: Find all past installments of “What the Tech?” and other insights on using technology in golf course management — from autonomous mowers to smartphone apps — at GCMOnline.com/Tech.

Within the category of multi-rotors, options range from a small quadcopter that can fit in the palm of your hand to much larger industrial models capable of carrying multiple highly sophisticated sensors. Determining which UAV is best for you boils down to a simple question: What do you want to do with the images you collect?

Seeing the golf course from a new perspective

Sometimes, it’s simply about expanding what can be seen. The comparison I like to make is with moisture meters. All of this “What the Tech?” and “Gadgets and Gizmos” stuff that we talk so much about really took off with the advent of portable moisture meters. The moisture meter became a game changer because it allowed superintendents to “see” beneath the surface of their greens to an extent that was not possible before. This device revealed far more than could be seen by anyone, no matter how many hours were spent walking on and examining greens.

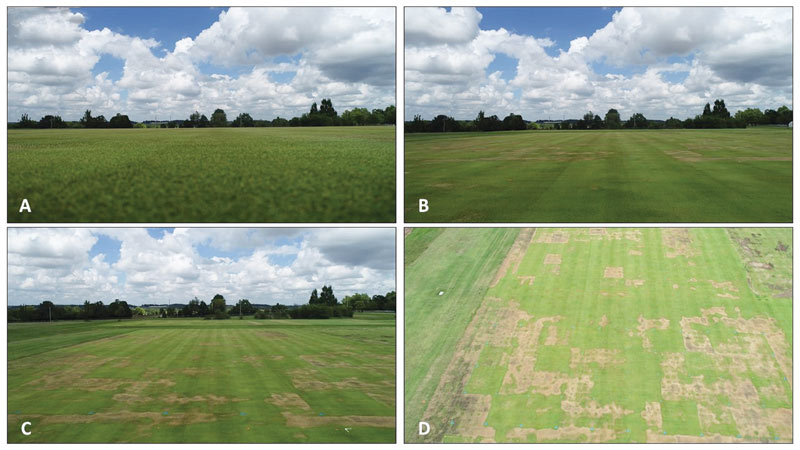

Figure 1. The images here were all taken on the same UAV flight over wetting agent research plots at the University of Arkansas’ agricultural research center in Fayetteville: (A) ground level, (B) approximately eye level, (C) above eye level, and (D) above the height of surrounding trees. Photos by Daniel O’Brien

Through technology, scouting became more precise, because the additional, valuable information translated directly to turfgrass health and necessary maintenance practices. In a similar way, aerial images from drones offer powerful and unique visuals that just can’t be replicated by standing on the ground (Figure 1, above).

It is important to point out the limitation of our moisture meter comparison. While snapshots (or videos) taken from drones provide valuable information for scouting, these images alone are not objective data in the same sense as volumetric water content (VWC) measurements taken with a moisture meter are. If it’s true data that you’re after (and not just images), that will require a more systematic approach.

Drone measurements and maps

That systematic approach is known as photogrammetry, and it’s essentially the difference between taking pictures with your drone and taking measurements with it. The primary issue that photogrammetry addresses is commonly referred to as ground sample distance. When you take a single overhead photo with a drone, the areas at the edge of the photo are farther away from the camera than the area of the photo that is directly beneath the camera. This leads to a skewed sense of distance within that image (each pixel in the photo does not represent the same distance on the ground).

To overcome this, photogrammetry doesn’t rely on a single overhead shot. Instead, UAVs fly a predetermined route over the entire area, capturing overlapping images at consistent intervals.

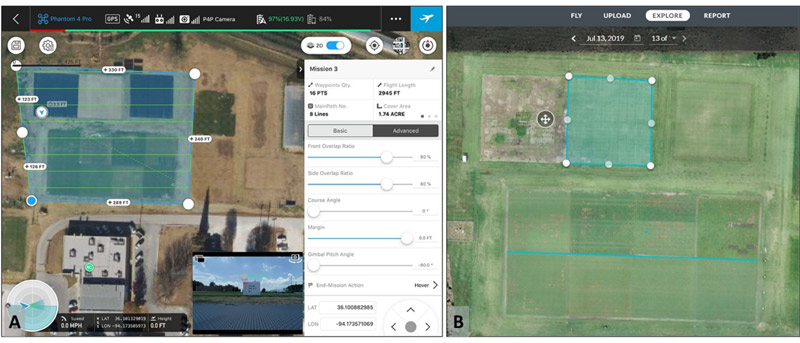

Software is then used to knit all of these individual photos together, creating one composite image called an orthomosaic. Through this approach, photogrammetry not only addresses the ground measurement issue, but also allows for much larger areas to be photographed and brought together, increasing both the scope and accuracy of what can be seen (Figure 2, below).

Figure 2. A screenshot from a flight planning app used for photogrammetric image collection (A, left). All photos are set to have 80% overlap in both forward and side directions and will ultimately be knit together into a single orthomosaic image (B, right) that allows for linear and area measurements.

With the right software, orthomosaics can be akin to a personalized Google Earth map on steroids — specific locations can be saved, and all types of measurement can be made, offering consistent comparisons over time and space. Once photogrammetry introduces this level of accuracy, practical applications for UAV images become extremely exciting. One of my favorites has been a study by Jordan Booth, CGCS, and the group at Virginia Tech, who used aerial images from drones in combination with a GPS sprayer to pinpoint applications for spring dead spot, greatly reducing the amount of product applied (1).

Thermal and multispectral sensors: More than meets the eye

It’s humbling to be reminded of how much of a golf course we can’t actually see. No matter how many hours are spent scouting, no matter how many photographs are taken, there are limitations to what the human eye can perceive. Our eyes only recognize energy that falls within the visible light portion of the much larger electromagnetic spectrum. Meanwhile, other wavelengths of energy reflected from turfgrass leaves (invisible to our eyes) offer valuable insights into plant health.

Even within the visible range of color that our eyes can see, if we were able to slice all of that information into individual bands of color, a great deal of information could be gained from looking at the relationships between different wavelengths. But for all of this, we need something more than our eyes (or a standard camera) to see and analyze it.

Two such types of sensors are thermal and multispectral. Thermal cameras detect energy outside the visible range, so the pictures they take reflect an object’s temperature rather than its color. Multispectral sensors, on the other hand, focus on specific bands of reflected energy. Research has shown that these particular bands are often associated with plant vigor, chlorophyll content and moisture stress.

Using the multispectral approach, plant health indices — such as normalized difference vegetation index (NDVI) and normalized difference red edge (NDRE) — can be quickly calculated and color-coded to an aerial image of your golf course. Such maps effectively illustrate the extent and boundaries of turfgrass experiencing moisture stress, nutrient deficiencies, etc. The growing popularity of these technologies in precision agriculture hinges largely on their potential for clearly illustrating critical data and offering greater lead time for addressing the underlying issues.

Drones on golf courses: Additional considerations

When it comes to using this technology on your golf course, the primary questions are: How much of this are you interested in doing yourself, and how much would you rather contract out? At every step along the way — from flying to data collection, processing and analysis — a certain level of investment and expertise is required. The ultimate goal is to maximize the information you have and the time you have to act on it, and outsourcing particular aspects of the UAV process may simply be the best route to obtaining the best information in a timely manner.

The DJI Phantom 4 Pro V2.0. For previous drone research, the authors used one of its predecessors, the DJI Phantom 4 Pro, which is no longer produced. Photo courtesy of DJI

Drone technology is expanding on all fronts, and there are plenty of options at each level of the process: new, more affordable aircraft; increasingly advanced sensors and cameras; software and services that produce highly informative, interactive and customizable maps; and the choice of doing it all in-house or hiring an outside service.

In the October issue of GCM, the second part of this series on drones will focus on the various options available and examine some of the specific drones, cameras, software and services best suited for golf courses.

Reference

- Booth, J., D. McCall and D. Sullivan. 2019. Site-specific management of spring dead spot: Using aerial mapping to enable precise applications of treatments for spring dead spot may cut costs and reduce fungicide use over time. Golf Course Management 87(4):80-85.

Daniel O’Brien is a former program technician, Doug Karcher is a turfgrass soil specialist and professor, and Mike Richardson is a professor in the Department of Horticulture at the University of Arkansas in Fayetteville, Ark.