Employees under age 25 are part of Generation Z, a growing segment of the workforce that, broadly, possesses certain qualities and motivations. To help staff his seasonal crew at Lake Geneva (Wis.) Country Club, superintendent Jeff Heaton (far right) turned to high school- and college-aged workers in 2019 and again this past summer. Photos courtesy of Jeff Heaton

In typical discussions between superintendents, the first question after general pleasantries will often be along the lines of, “Got any projects going on?” More recently, however, that first question has become, “Have you been having trouble finding workers?”

Staffing a large, seasonal golf course maintenance crew has become difficult.

Correction: very difficult.

Recently here at Lake Geneva (Wis.) Country Club, we have targeted students at local colleges and high schools to help fill out our in-season maintenance crew of around 20 members. We use pamphlets and postings and have discussions with teachers and coaches.

Early in the 2019 season, I was lucky enough to have a high school-aged candidate answer my posting on the website Indeed. I hired him, and soon after was flooded with applications from his friends and acquaintances. In just a few weeks, I had 14 high school- and college-aged employees. In June of that year, we were overstaffed by at least five. Excited by the potential for productivity, I dropped my concerns for labor cost and decided to let things fly.

It soon became apparent, however, that the allure of a paycheck wasn’t motivation enough for some of these younger members of my staff, who belonged, depending on the definition used, to a generation or two removed from mine. At 42, I am considered a member of Generation X.

I had to find a way to reach the Generation Z members of my staff beyond simply offering a day’s pay for a day’s work.

Good workers and ‘ghosting’

With such a large crew, we were able to start a sectional program — four teams of two employees, each maintaining five or six holes. Older and more experienced employees performed as operators of fairway and rough units. The students worked in the sections, doing most of the walk-mowing, raking and other tasks that require less skill. The sectional workers were thoughtful and willing participants in our physically rigorous program.

Double-cutting the greens of Lake Geneva Country Club’s 18-hole course is equivalent to an 8-mile walk, a task not too tall for many of the younger workers.

Unfortunately, though, attendance became an issue.

The operators were reliable, but counting on the sectional workers became problematic. Unexcused absences and tardiness were rampant. I recall a morning with seven absences without any explanatory call or text. Nearly every day, at least one employee was late or absent.

However, I remained patient. Morning meetings would be tinged with disappointment as we scrambled to schedule around missing workers, but I resisted the urge to send any objects flying across the room — even though it would have felt so satisfying to unload on some unsuspecting whiteboard marker. Remembering myself at 17 years old, I had to feel empathetic. It is a lot to ask a youngster to wake up at 4 a.m., six days a week, and show up ready to work a tiring job for $11 an hour.

Talkin’ ’bout my generation

The problem with lumping groups of people together by their birth years and slapping a catchy label on it is that it’s just so imprecise.

Members of the baby boomer generation — based on the boom of babies born after World War II — were born between 1946 and 1964. That’s the only generation officially defined by the U.S. Census Bureau. After that, things get considerably murkier.

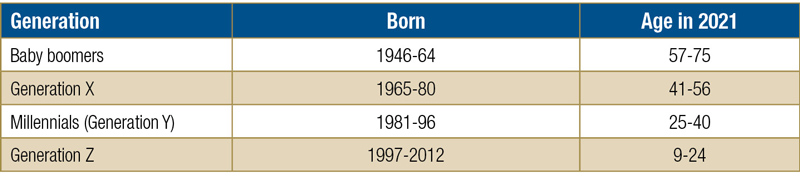

Though specifics vary depending on who is doing the defining, here’s one breakdown of the generations most active in the workplace, as defined by the Pew Research Center.

Editor’s note: The Pew Research Center offers much more insight on Generation Z, noting that all generational designations are a lens, not a label.

Appealing to different motivations

We tried to encourage attendance with a raffle drawing for vendor swag, golf clubs and gift cards to the pro shop. We issued five tickets to each team member. Each unexcused absence resulted in the loss of one raffle ticket, thereby reducing or eliminating the chance to win. It was more popular than I had anticipated, but absences remained a problem.

We had frequent cookouts, doughnuts in the morning, occasional pizza for lunch, pep talks and lavish praise when actually earned. One-on-one office conversations and thoughtful text chains helped with some staffers, but not all.

Golfing privileges were offered during certain times of the week. We never threatened to revoke that privilege from those who respected the rules applied by our head professional. I think it is important for maintenance employees to spend time on the course as golfers — it can help an inexperienced crew member see the course from the vantage of the people signing our checks.

Right: New crew members needed training and close supervision, but they learned quickly, and Heaton found the Gen Z staffers to be key cogs in his maintenance machine.

We made lunch break optional. Crew members who worked through lunch were released at noon rather than 1 or 2 p.m. They seemed to love this. We took almost any avenue to get the sectional work done and be in a position to let them go early. Staying late to help with projects and watering was always encouraged, but even time-and-a-half overtime wage did little to entice volunteers. They just wanted to go home.

When all else failed, I fired two employees with the worst attendance records. Things improved immediately. Patience and a soft hand kept the rest of the crew intact and in good spirits. No one quit midseason.

‘Best job I ever had’

At the end of the year, my labor budget was in good shape. Short days and absences had kept the hours consistent with having 20 employees when we actually had 25. Overstaffing also allowed employees to be held “in reserve.” Reserves could be plugged into assignments left vacant by those who did not show up.

My assistant superintendent and intern were only a few years older than the younger staff members and helped me relate to them. They also served as examples of the advancement possible in the industry. Recent high school graduates in search of direction found them and their careers intriguing.

Right: Despite the early mornings and strenuous labor, the young crew members at Lake Geneva Country Club had great attitudes and took pride in their work.

Outstanding individuals earned a discussion with me about a future in turfgrass. Our club offers deserving and proven employees an opportunity to attend low-cost online associate degree programs. We have enrolled employees in the Penn State World Campus online turfgrass science program. The costs are incorporated into our operational budget. Going forward, I hope to cultivate more interns and assistants within our program. Some crew members not given this discussion eventually heard about it and improved their performance in hopes of earning that possibility themselves.

Our young crew seemed tired by the end of a tough season and started to drop off, returning to school or starting another job — but not before we heard comments like, “Best summer of my life” and “Best job I ever had.” And the most satisfying: “I will definitely be back next year.”

Despite the challenges of the coronavirus pandemic, we had similar success with our Gen Z staffing strategies this past season. There was one notable change, however: There was even more interest in pursuing a career in the turf industry. Perhaps there is more to this success story still to be written.

Jeff Heaton, a 10-year member of GCSAA, holds bachelor’s degrees in English from the University of Puget Sound and agronomy from Texas A&M University. As part of the golf course maintenance industry, Heaton has worked in Washington, Colorado, Illinois and Wisconsin and has been director of grounds at Lake Geneva (Wis.) Country Club for eight years.