The previously dilapidated area in the Ivanhoe neighborhood of Kansas City, Mo., has been transformed into block-long green space — the Harris Park Golf and Learning Center across the street from the Midtown Sports and Activity Center. Photo by Andrew Hartsock

It’s a gorgeous spring night in middle America.

Temperature in the 70s, light breeze, a couple of high clouds and maybe a half-dozen contrails crosshatching the blue sky here in Flyover Country.

On the air wafts the scent of someone’s dinner ... the sounds of a nearby basketball game ... an occasional car horn ... maybe a distant siren ... the hint of music from a moving car ... the bark of a dog.

Chris Harris takes a deep breath, stretches out his arms.

“It really is perfect,” he says, looking out at the golf course that bears his name. “It’s so peaceful and quiet. Everything is just ideal.”

Harris, 50, is the chief caretaker for the Harris Park Midtown Sports and Activity Center and the Harris Park Golf and Learning Center, but he’s so much more than that. He’s their visionary. And to understand his statement — to appreciate his is no ordinary epiphany that, yes, golf courses really can be pretty easy on the eye — it’s imperative to understand Harris’ vision.

Because to compare Harris Park to any of the game’s aesthetic and architectural marvels — the Pebble Beaches or Augustas or Shinnecock Hillses — or even the local lovely 18 is to do a disservice to all, because the marvel at Harris Park doesn’t lie in its landscaping, or its geography, or its maintenance.

Harris Park’s magnificence is that it exists at all.

“You wouldn’t think,” Harris says, “that you’d find this right in the middle of one of the worst neighborhoods in Kansas City.”

‘Something was wrong’

Harris Park is located in what is known as the Ivanhoe neighborhood in Kansas City, Mo., which, according to the Urban Neighborhood Initiative, was settled in the 1890s by German immigrants.

The UNI says in the 1930s, the neighborhood was populated by middle- and working-class white families before suburban flight. By the 1980s, the UNI says, “The Ivanhoe neighborhood was marked by drug houses, crime, falling property values and continued decline in population.”

Chris Harris knows all about that. It’s where he grew up.

“When I was a kid, I knew something was wrong with my neighborhood, but I didn’t know what it was,” he says.

The neighborhood’s decline was evident in the abandoned homes and overgrown lots. Harris’ parents, Henry and Alee Harris, were the first to see the value in that decrepit land.

“My dad started the trend of buying the land around here,” Chris Harris says. “When I got older, in high school and in college, I told him I wanted to teach the basis of life through sports, and I wanted to build a park to do it. This was on paper in ’94. My dad said, ‘Go for it.’”

Chris Harris, the visionary behind the Harris Park project. Photo by Andrew Hartsock

Harris, a graduate of nearby Westport High School, ventured only slightly farther afield to attend Penn Valley Community College, a mere 2½ miles away. In 1996, Harris led Penn Valley to the NJCAA Div. II national basketball championship, and he eventually served as an assistant coach in minor-league basketball.

Into the late ’90s, Harris kept buying vacant lots, sometimes for only a few thousand dollars. Over the years, he bought all the lots on the west side of Wayne Avenue between 40th and 41st streets and raised money — one account says close to $2.5 million — and in 1998 created the Harris Park Midtown Sports and Activity Center, with a park and basketball court.

A playground, miniature golf course and a volleyball court followed.

“I just thought I could use sports as a catalyst,” Harris recalls. “I thought we could use sports and clean up the neighborhood and just change the mindset of the people who live here.”

Harris recalls buying a saw — $60, on clearance — at a local big-box hardware store and clearing the land by hand. He also continued to buy lots, on the east side of Wayne Avenue, surrounding his childhood home at 4029 Wayne.

As a kid, he’d bounce down those steps in front of that old bungalow and, without looking too far, be able to find a place to play basketball or baseball or volleyball. But golf?

He seems to remember tagging along with a friend’s family and playing once as a child, though the memory is faint.

“I did get to play very early. I did like it, and I wanted to play, but there was nowhere I could play. The closest place to play is Swope, and I don’t think the bus even runs out there,” Harris says of Swope Memorial Golf Course, a good 7 urban miles away. “I could go outside and play basketball and baseball and volleyball, but there was nowhere to play golf. I feel like, if I had a chance to play as a kid, I could have been good.

“I grew up and realized, I can literally build a golf course. You never know what’s going to be the spark. I said I wanted to do a basketball court, and I wanted to build a small golf course. Now I have a golf course.”

‘I always just give it my all’

Phase I of the Harris Park Golf and Learning Center opened late last year. The pitch-and-putt course features six synthetic-turf tees and two synthetic-turf greens, with a zoysiagrass fairway, two bunkers and fescue roughs.

Harris (perhaps generously) estimates the longest shot at 65 yards, and a creative combination of tees and greens, not to mention four holes per green, can lead to a 12-hole round.

Phase II calls for another green with three more tees — more creative routing makes for a potential 18-hole round — and a separate nine-hole putting course, plus a clubhouse.

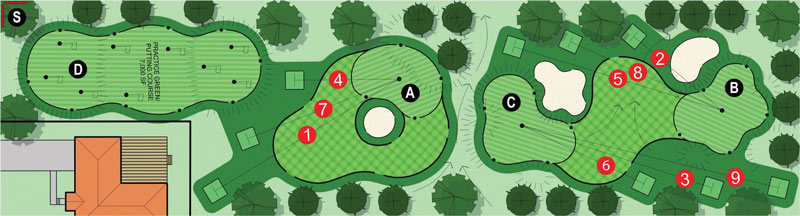

A look at the grand plan for Harris Park Golf, including the under-construction second phase (the new green is marked as A on the illustration; the putting course is D). Illustration courtesy of Chris Harris

The only things standing in the way: funding, which is about $100,000 away from a $250,000 goal; and that home at 4029, where Chris Harris grew up.

In April, Harris had the home leveled, a “bittersweet” moment that simultaneously closed one chapter and opened another. Construction on Phase II began the final week in June.

“When I was playing basketball and took a shot, I didn’t care if it went in,” Harris says. “I didn’t care if we won, lost, whatever. All I did was give it my all. That has carried over into my life. I always just give it my all.”

Man on a Mission (Hills)

Harris admits it’s one thing to see a neighborhood in decline and lament it, quite another to buy up what amounts to nearly a city block and build an extensive, public-use green space upon it.

And he’d be among the first to admit that it wouldn’t have been possible without tremendous support, both fiscal and physical.

Mission Hills Country Club is sort of the epicenter of that support as far as the Harris Park golf course is concerned.

Mission Hills is 4½ miles — yet worlds away — from Harris Park. Harris recalls passing Mission Hills CC, located just across the state line, in tony Mission Hills, Kan. — recently ranked No. 3 on the Forbes list of most affluent neighborhoods in America — and marveling.

“I just started driving past, driving back and forth, looking at their grass,” he says. “Mission Hills had all this beautiful grass. And I started thinking, I have just as much land and just as much grass as they do. The only difference is landscaping. I started asking around, and I asked who the guy was who was overseeing all that grass.”

The answer at that time, 2016, was superintendent Brad Gray.

Golfers at Harris Park will eventually be able — with a little creativity — to carve out an 18-hole round by mixing and matching. Phase I of the course, which opened in late 2018, features six tees, two greens, two bunkers and a fairway. Phase II will include another three tees, a fairway, a bunker and a nine-hole putting course. Photo by Andrew Hartsock

Gray, still a Class A superintendent and 20-year member of GCSAA, now works in sales, for Professional Turf Products. He recalls the day Harris walked in the door.

“He came in and started to ask questions, like, where could he get flagsticks and cups? I thought that was odd,” Gray says. “I said, ‘What are you trying to do?’ He said he was trying to start a golf course. ‘Where?’ Uh, downtown (actually midtown) Kansas City. I thought, ‘What?’ He explained he was trying to rejuvenate a neighborhood. We had all these extras, so I gave him a set of, oh, five flagsticks and five cups and flags so he could start what he was doing.”

That could have been the end, but it wasn’t.

Harris kept coming around, kept asking questions. One in particular resonated with Gray.

“He said, ‘Hey, can I get a job?’ In this industry, anyone asking for a job ... anyone would take that in a heartbeat,” Gray says. “He said, ‘I want to learn how to take care of a golf course.’”

Harris worked weekends at Mission Hills CC — his “real” job, then as now, was to find housing for the homeless for Truman Medical Center — for a season, primarily on the bunker crew.

“He was always asking questions,” Gray says. “He loved being on the golf course. We tried to train him on other things, but that’s hard on the weekends, when you’re just trying to stay ahead of play.”

A watershed moment came when a flood destroyed one of the Mission Hills greens.

“It was bittersweet, because I didn’t want to see what they had get ruined, but I wanted to see how they built it,” Harris says. “I saw how they brought in sand and built it up.”

‘People responded’

Mission Hills was more than just a place to learn.

The club’s members got involved in the Harris Park projects. A connection was made between Harris and Kansas Golf Hall of Famer Frank Kirk, who lent his considerable fundraising experience and connections and helped establish the activity center as a nonprofit.

CE Golf Design lent aid, as did the Midwest Section PGA, the architectural firm HOK, and Trozzolo Communications. John Deere donated $25,000 and equipment. A group of members of the Heart of America GCSA held an extensive work day at the course, and The First Tee of Kansas City announced the course would become part of its network. The First Tee started offering free lessons twice a week at Harris Park beginning mid-July.

“I just told my story, and people responded,” Harris says.

The community, by and large, has responded in kind. While there are some obvious, tangible results — the immediate neighborhood is well maintained; one house recently sold for more than $100,000, a previously unheard-of price for that part of town; new developments are springing up around Harris Park, anchored to its green space; and property values, Harris says, have gone up 100, 200, 300 percent — there are less obvious signs. Attitudes, outlooks — optimism — can’t be measured.

Harris shrugs.

“Really, all I’ve done is pick up trash and cut grass. That’s it,” he says. “And it’s changed the mindset of the community, and even people outside the community. When you really get to the heart and core of it, it’s landscaping. Most people see landscaping to this degree and say it’s just not doable, or not common. But it’s just grass, and the landscaping is beautiful. And it’s done so much for this community and the people of this community.”

New homes have sprung up behind Harris Park, and property values have gone up dramatically in a neighborhood once considered among the worst in Kansas City, Mo. Photo by Andrew Hartsock

Harris no longer lives on Wayne Avenue. He lives downtown, in his “362-square-foot mansion,” but he still very much considers himself a part of this community.

Harris Park is about more than just golf. He runs basketball leagues on the court across the street for adults and youth, and he wants that to be the model for golf on the east side — designated nights for kids, families or adults-only. He has arranged a fitness program through his employer that includes health checks, fitness classes at the park and a summer weight-loss challenge.

He cites recent demographic information that shows life expectancy in the Ivanhoe neighborhood is 76 years. A short 10-minute drive west to the next ZIP code over, an area that encompasses the upscale Country Club Plaza shopping area, the life expectancy is nearly 9 years longer.

“I think this goes hand in hand with cleaning up the community,” Harris says. “I say, this is 5 percent sports, 95 percent education. I’m using sports as a catalyst to raise life expectancy.”

‘That’s in the middle of the ’hood?’

The first time Jamar Brown played at Harris Park, he could hardly believe it.

“Honestly, I was amazed,” he says. “I was in shock. I said to my wife, ‘You’re not going to believe this.’ She knows I play golf here and there. I showed her a picture, and she said, ‘That’s in the middle of the ’hood?’ Yes. Yes, it is.”

Brown is a youth basketball coach, which is how he crossed paths with Harris. Harris noticed Brown had a set of golf clubs and invited him to Harris Park.

Brown isn’t from Ivanhoe, but he did grow up nearby.

“I was always in that (Ivanhoe) neighborhood,” says Brown, 39. “I had been down there quite a bit. I remember it was pretty run-down. It was rough. There wasn’t a lot of violence. It wasn’t too out of control, but it was pretty rough. But Mr. Harris did a lot to it. He put a lot into it, and everybody is more respectful toward it.”

Maybe a bit too respectful.

Before the course was built, Harris made it plain that everybody was welcome on the west side, on the basketball court and the park and the miniature golf course. But the east side, where his old childhood home once stood, was another matter.

“In a way, I was my own worst enemy,” he says. “I used to not allow anyone on this side of the street. Out of respect for me, they’re still a little ... hesitant ... to come on this side of the street. They’re still following the rules. But in a way it’s good, because we don’t want to have these kids up here by themselves, with golf clubs and balls unsupervised. I really need to be up here supervising.”

But if an adult happens to be passing through and stumbles upon Harris Park, notices the beautiful green space and the course and just happens to have a set of sticks in the trunk?

“Great,” Harris says. “Come on. Play. I encourage it.”

A dream come true

There’s no telling what’s next for Harris Park once Phase II is complete and The First Tee folks start holding more events there. Did Harris mention the clubhouse? There’s still a house standing — not his childhood one — and part of Phase II includes gutting that house and turning it into a clubhouse for educational efforts.

Harris is transitioning to a part-time job with Truman Medical Center so he can spend more time at the activity center, “So people know that every ounce of my work is going into this,” he says. “I had to let my job go. But there’s a whole other level of beautification we can go to.”

Synthetic greens at Harris Park have four holes each. Tees are also synthetic, while the fairway is zoysiagrass and the rough is fescue. Photo by Andrew Hartsock

Standing on the course’s high point, overlooking the entire track, Harris sweeps his eyes over all he has built. From here, he can see his course; the barren land where his boyhood home stood; the park, playground and basketball court across the street.

“This is my favorite part on the whole course,” he says. “I think about Mission Hills, and it was just beautiful to me. And to stand here now, to have something like that, it’s like everything I ever dreamed came true.”

And yet ...

His gaze sweeps north, to the one lot on the block he does not own. Like so many of the tracts just a few blocks away, in any direction, that more resemble the blighted Ivanhoe of Harris’ youth, that lone lot north of the golf course is unkempt. It’s overgrown, scrubby ... a stark contrast to the manicured course to its south.

From here, Harris can see it all — Ivanhoe’s past, present and future. To his right, a basketball game is being played on the basketball court he built to start this whole project. Ahead is his golf course, and the site of his childhood. To his left, beyond a stand of trees, is a row of obviously new developments: lovely, freshly painted homes that have sprung up abutting, unbelievably, a golf course in the middle of one of the worst neighborhoods in Kansas City.

After a short reverie, Harris glances behind him, at the undeveloped lot. He gestures to the unmarked but obvious property line, indicating left and right — but also up.

“I’d like to put a leaderboard here,” Harris says. “I want a nice leaderboard ...”

Andrew Hartsock is GCM’s managing editor.