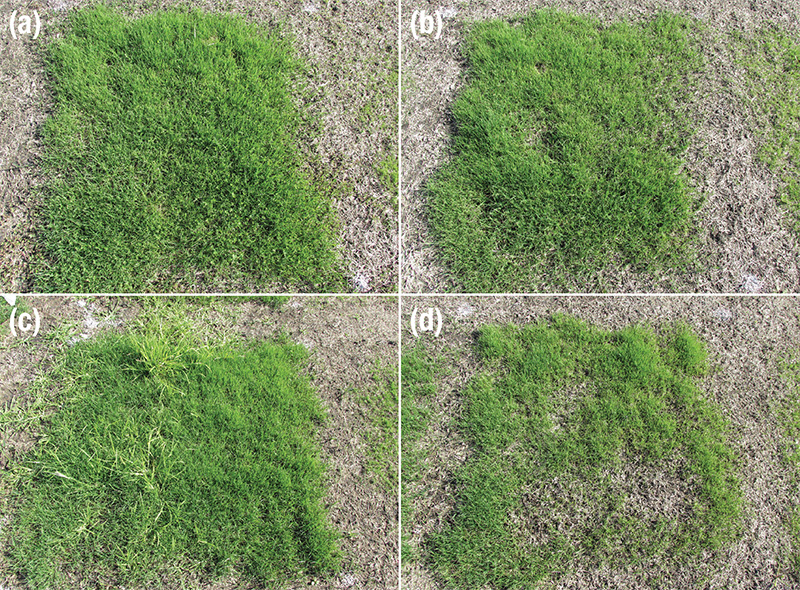

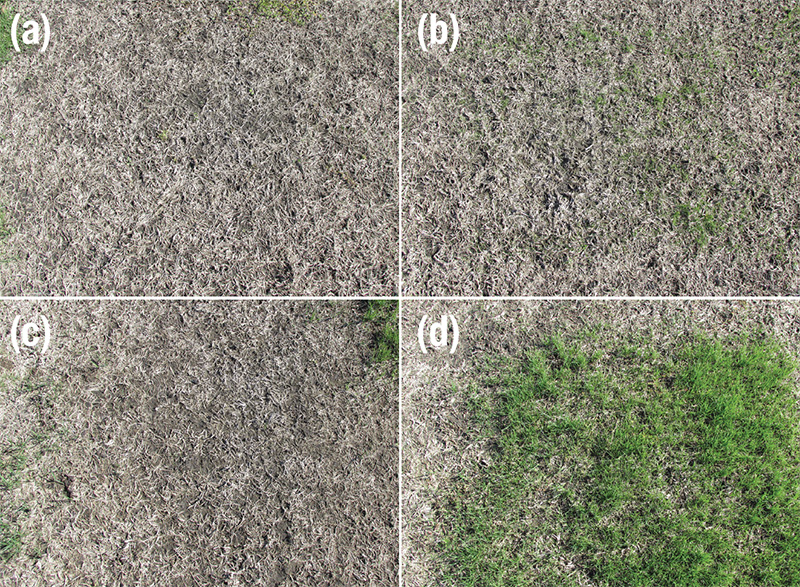

Figure 1. Tall fescue seeded in untreated control (a); tall fescue seeded the same day as application of Trimec Classic (b), Drive XLR8 (c) or SedgeHammer (d). Photos taken six weeks after herbicide application in Manhattan, Kan. Photos by Dani McFadden

Mid-August through early September is the optimum time to seed cool-season turfgrasses in the Midwest. Turfgrass seeded during this optimal time will increase the chance for successful establishment of a dense stand that withstands the stress of winter.

Removal of annual and perennial grassy and broadleaf weeds is commonly required during turfgrass establishment. Effective weed control before seeding helps decrease competition and increase seedling growth. However, the use of postemergence herbicides

often requires that seeding be avoided for a specified period after application, and product labels typically include information on how long seeding should be delayed.

Most preemergence herbicides cannot be used near the time of planting or after seeding turfgrasses, as they often injure newly seeded and immature cool-season turfgrasses, causing establishment to fail. A few herbicides can be applied at the time of seeding

to prevent the onset of weed encroachment, including siduron (Tupersan, PBI-Gordon), mesotrione (Tenacity, Syngenta), and topramezone (Pylex, BASF Corp.).

Much of the research related to herbicides and turf establishment has evaluated their effects on turfgrass growth and quality when applied after seedling emergence (1, 10, 7). However, there are many instances when turfgrass managers unknowingly seed

into areas void of turf in which herbicides were recently applied. In other cases, they do not have the ability to wait on the recommended reseeding interval after herbicide application. There is a need to investigate which commonly used herbicides

do not inhibit seedlings planted into treated areas. Therefore, the objective of this research was to determine the influence of three selective postemergence grass, broadleaf and sedge herbicides on growth of Kentucky bluegrass and tall fescue seeded

between zero and 14 days after application.

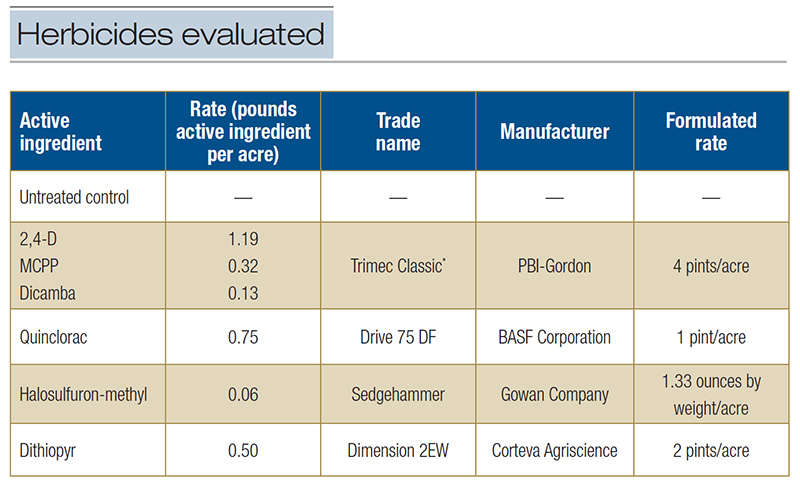

Table 1. Herbicides evaluated for effects on Kentucky bluegrass and tall fescue seeded after application at the Rocky Ford Turfgrass Research Center in Manhattan, Kan., and the Ohio Agricultural Research and Development Center in Wooster, Ohio, in 2019. Kentucky bluegrass and tall fescue were seeded 0, 3, 7 and 14 days after herbicide treatment. *Rate presented as pounds acid equivalent per acre for each active ingredient.

Materials and methods

Research was conducted at the Rocky Ford Turfgrass Research Center in Manhattan, Kan., and the Ohio Agricultural Research and Development Center in Wooster, Ohio. The experimental design was a three-way factorial, randomized complete block with four replications

of plots measuring 4 feet by 4 feet (1.2 meters by 1.2 meters). Main factors included two turfgrass species (Kentucky bluegrass and tall fescue), four seeding intervals (0, 3, 7 and 14 days after herbicide application), and five herbicide treatments

including an untreated control (Table 1).

Prior to study initiation, existing vegetation was scalped to 0.5 inches (1.27 centimeters) following sequential applications of glyphosate. Herbicide treatments were applied in Manhattan using a CO2-pressurized, hand-held spray boom calibrated to deliver

43 gallons per acre (402 liters per hectare). Prior to seeding plots within each respective interval, a three-tine rotary cultivator was used to lightly disturb the top 1 inch (2.54 centimeters) of the soil surface in each plot. A starter fertilizer

(14% nitrogen-20% phosphorous-4% potassium) was applied to deliver 1 pound phosphorus per 1,000 square feet (49 kilograms per hectare). Kentucky bluegrass (24.8% Gladstone, 24.7% Shamrock, 24.7% Wildhorse and 24.6% Blue Coat) was seeded at 3.9 pounds

pure live seed (PLS) per 1,000 square feet (190 kilograms per hectare) and tall fescue (36.8% Copious, 31.1% Technique and 30.9% Leonardo) was seeded at 10.2 pounds PLS per 1,000 square feet (498 kilograms per hectare).

Both the granular fertilizer and seed were spread independently using a shaker bottle in multiple directions. Irrigation was withheld until 24 hours after herbicide application. Following the 24-hour period, supplemental irrigation ran three times daily

to apply a total of roughly 0.1 inch (0.25 centimeter) of water. Plots were not mowed throughout the duration of experiment.

Prior to study initiation in Wooster, existing vegetation was scalped to 1 inch (2.54 centimeters), and clippings were collected followed by sequential applications of glyphosate. Herbicide treatments were applied using a single-nozzle CO2-pressurized

backpack sprayer with a spray volume of 44 gallons per acre (412 liters per hectare). Plot size, soil preparation, fertilization, seeding, irrigation and mowing in Wooster were the same as described in Manhattan.

At both locations, Kentucky bluegrass and tall fescue cover were visually rated weekly using a scale of 0% to 100% cover (0% = no visible cover; 100% = full cover of experimental plot). Normalized difference vegetation index (NDVI) values were recorded

at 21, 28 and 42 days after seeding. The NDVI has a range of minus 1 to plus 1, with higher values indicating healthy dense vegetation.

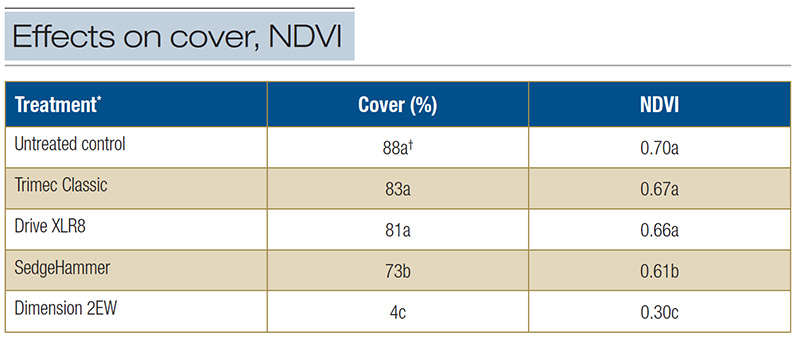

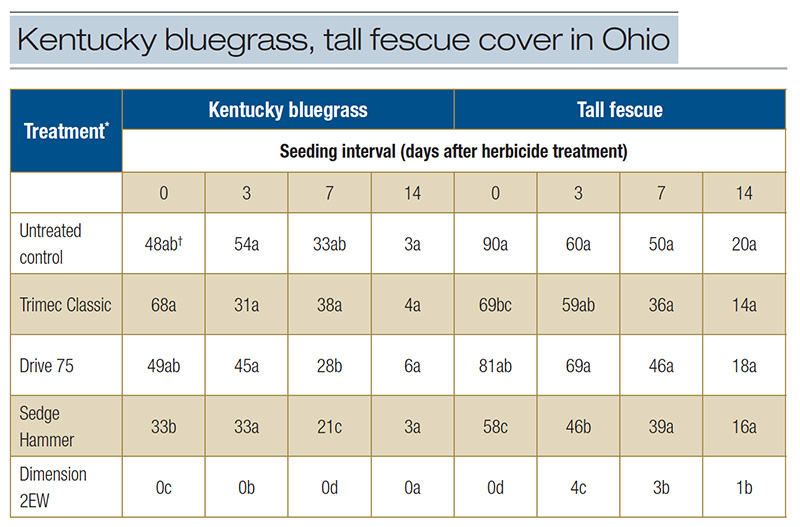

Table 2. Main effects of herbicide treatment on Kentucky bluegrass cover and NDVI in Manhattan, Kan., six weeks after herbicide application.

*Herbicide treatments were applied on Sept. 6, 2019, at the Rocky Ford Turfgrass Research Center in Manhattan, Kan.

†Means are overall seeding intervals; those followed by the same letter in a column are not statistically different according to Tukey’s HSD (P≤0.05).

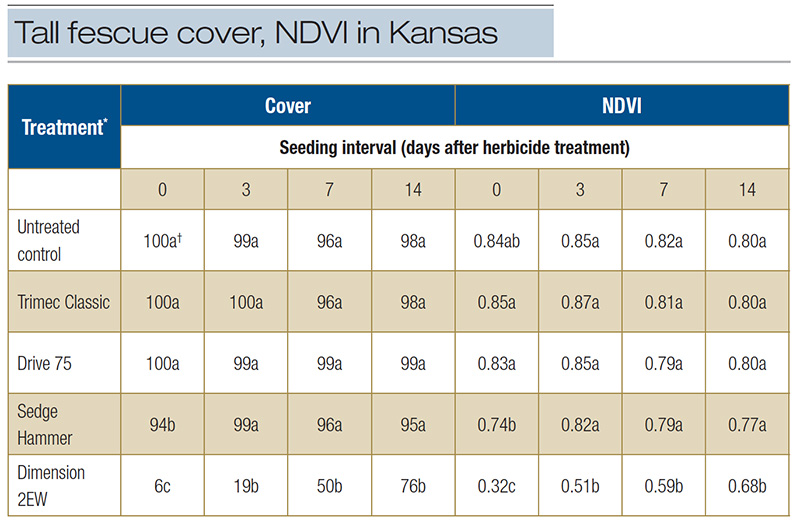

Table 3. Effect of herbicide treatment by seeding interval interaction on tall fescue cover and NDVI in Manhattan, Kan., six weeks after herbicide application.

*Herbicide treatments were applied Sept. 6, 2019, in Manhattan, Kan. †Means followed by the same lower case letter in a column are not significantly different within each seeding interval according to Tukey’s HSD (P≤0.05).

Herbicide effects on Kentucky bluegrass

Six weeks after herbicide application, Kentucky bluegrass reached over 80% cover in the untreated control and plots treated with Trimec Classic (2,4-D + MCPP + dicamba; PBI-Gordon) and Drive 75 DF (quinclorac; BASF Corp.) (6). However, in Manhattan, seeding

into plots treated with SedgeHammer (halosulfuron-methyl; Gowan Co.) and Dimension 2EW (dithiopyr; Corteva Agriscience) reduced cover and NDVI values compared to the untreated control (Table 2).

Tall fescue cover and NDVI were generally less affected by postemergence herbicides than was Kentucky bluegrass. Tall fescue cover in Manhattan was above 94% for all treatments six weeks after herbicide application (Table 3). Seeding into SedgeHammer-treated

plots the same day of herbicide application reduced tall fescue cover; however, cover reached 94% by six weeks after application. Cover of 100% was observed in the untreated control and plots treated with Trimec Classic or Drive (Table 3, Figure 1).

NDVI values for tall fescue seeded into SedgeHammer were also reduced at 0 DAT (Manhattan) and 7 DAT (Wooster; data not shown).

Seeding in Wooster was initiated later than in Manhattan, which resulted in less cover six weeks after seeding; no treatment had over 55% cover. This was due in large part to lower temperatures. Kentucky bluegrass seeded 7 days after treatment (DAT) into

SedgeHammer-treated plots had only 21% cover six weeks after seeding, while untreated Kentucky bluegrass averaged 33% cover. No differences were observed among other postemergence herbicides in cover compared to the untreated control regardless of

seeding interval.

Tall fescue cover and NDVI were generally less affected by postemergence herbicides than was Kentucky bluegrass. Tall fescue cover in Manhattan was above 94% for all treatments six weeks after herbicide application (Table 3). Seeding into SedgeHammer-treated

plots the same day of herbicide application reduced tall fescue cover; however, cover reached 94% by six weeks after application. Cover of 100% was observed in the untreated control and plots treated with Trimec Classic or Drive (Table 3, Figure 1).

NDVI values for tall fescue seeded into SedgeHammer were also reduced at 0 DAT (Manhattan) and 7 DAT (Wooster; data not shown).

Kentucky bluegrass seeded into Trimec Classic-treated plots, regardless of seeding interval, had similar live green vegetation compared to untreated plots (NDVI data not shown). NDVI was reduced when Kentucky bluegrass was seeded into SedgeHammer-treated

plots at 0, 3 or 7 DAT; Kentucky bluegrass treated with this herbicide had NDVI values lower than 0.41.

Tall fescue cover and NDVI were generally less affected by postemergence herbicides than was Kentucky bluegrass. Tall fescue cover in Manhattan was above 94% for all treatments six weeks after herbicide application (Table 3). Seeding into SedgeHammer-treated

plots the same day of herbicide application reduced tall fescue cover; however, cover reached 94% by six weeks after application. Cover of 100% was observed in the untreated control and plots treated with Trimec Classic or Drive (Table 3, Figure 1).

NDVI values for tall fescue seeded into SedgeHammer were also reduced at 0 DAT (Manhattan) and 7 DAT (Wooster; data not shown).

Herbicide effects on tall fescue

Tall fescue cover and NDVI were generally less affected by postemergence herbicides than was Kentucky bluegrass. Tall fescue cover in Manhattan was above 94% for all treatments six weeks after herbicide application (Table 3). Seeding into SedgeHammer-treated

plots the same day of herbicide application reduced tall fescue cover; however, cover reached 94% by six weeks after application. Cover of 100% was observed in the untreated control and plots treated with Trimec Classic or Drive (Table 3, Figure 1).

NDVI values for tall fescue seeded into SedgeHammer were also reduced at 0 DAT (Manhattan) and 7 DAT (Wooster; data not shown).

The only preemergence herbicide applied in this study, Dimension 2EW, reduced tall fescue cover at all four seeding intervals after application. Tall fescue reached 6% cover when seeded the same day of Dimension 2EW application, whereas that seeded at

7 and 14 DAT had a mean cover of 50% and 76%, respectively (Table 3). The amount of growth in plots seeded at 7 and 14 DAT was likely due to a loss of herbicide residual in the soil before seeding. After seeding at 0 DAT, all plots in the experiment

received irrigation three times daily, including plots to be seeded at 3, 7 or 14 DAT, which may have encouraged dithiopyr degradation.

The greatest impact of seeding time after application was evident in Wooster, where temperatures decreased as DAT progressed. Untreated tall fescue had 90% cover 0 DAT; however, cover was reduced to 20% at 14 DAT. This was the trend for all treatments

in Wooster (Table 4). Trial initiation timing was likely a major factor in differences in locations. In Manhattan, experimental plots were seeded on Sept. 6, 2019, and the average daily high and low air temperatures throughout the study period were

72 F and 51 F (22 C and 11C) respectively. In Wooster, experimental plots were seeded on Oct. 2, 2019, and the average daily high air temperature was 57 F (14C), while nighttime low air temperatures averaged 35 F (2 C) throughout the seven-week rating

period. The late trial initiation in Wooster caused less Kentucky bluegrass and tall fescue emergence and growth and lower NDVI values compared to data collected in the Manhattan field trial. This was to be expected, as temperatures were below the

ideal range limiting growth (4).

Table 4. Effect of herbicide treatment by seeding interval interaction on Kentucky bluegrass and tall fescue cover in Wooster, Ohio, six weeks after herbicide application. *Herbicide treatments were applied on Oct. 2, 2019. †Means followed by the same lower case letter in a column are not significantly different within each seeding interval according to Tukey’s HSD (P≤0.05).

Turf response compared to label guidelines

The Trimec Classic label indicates that grass seed can be sown three to four weeks after application (8), and our data indicate the seeding interval could be reduced based upon results herein under the conditions evaluated in these experiments. These

three active ingredients (2,4-D + MCPP + dicamba) have relatively short persistence in the soil and exhibit low to moderate levels of soil adsorption (9). Presumably, these factors reduced the likelihood that cover was affected when seeding after

application.

The Drive 75 DF product label indicates that its use before or after seeding or overseeding a turf area will not significantly interfere with the turfgrass seed germination and growth of grass types identified as tolerant or moderately tolerant (1). The

application of this product did not influence growth of Kentucky bluegrass or tall fescue in Manhattan. Kentucky bluegrass and tall fescue are both listed as highly tolerant turfgrasses on the Drive 75 DF product label.

The SedgeHammer label specifies four weeks between application and seeding or sodding of turfgrass (3), and research herein supports waiting over 14 DAT before seeding Kentucky bluegrass or tall fescue. Tall fescue emerging in plots treated with halosulfuron-methyl

exhibited minor chlorosis; however, turf had fully recovered six weeks after herbicide application.

More research could be conducted to determine if a waiting period less than four weeks after halosulfuron-methyl application is supported.

Throughout the field studies, both turfgrass species were highly sensitive when seeded into Dimension 2EW-treated plots. This was expected, as Dimension 2EW was included as a “treated” control at both locations. The Dimension 2EW label indicates

reseeding or overseeding of treated areas within three months after application may inhibit establishment of desirable turf (2). However, Kentucky bluegrass exhibited greater sensitivity to dithiopyr than tall fescue. As stated previously, there was

an increase in tall fescue establishment in the later seeding intervals after application (Figure 2).

Warm soil temperatures in the early fall could have enhanced degradation, compared to an application during cool, spring conditions. More research is needed to evaluate the effects of irrigation on tall fescue emergence in dithiopyr-treated plots, as

suggested by results in Manhattan.

Overall, this study indicates that seeding between 0 and 14 days after an application of Trimec Classic or Drive 75 DF has little or no effect on Kentucky bluegrass or tall fescue growth under the conditions evaluated in these experiments. SedgeHammer

was the only postemergence herbicide that reduced Kentucky bluegrass and tall fescue cover when seeded within 14 DAT, which matches warnings on the herbicide label. This research demonstrates that turfgrass managers who unknowingly seed into areas

treated with Trimec Classic or Drive 75 DF within 0 to 14 DAT will likely observe successful establishment of Kentucky bluegrass and tall fescue. This research was initiated in the fall, when soil temperatures are ideal for cool-season turfgrass growth.

Variables such as season and irrigation amounts could potentially affect the results turf managers observe.

However, herbicide manufacturers must consider making changes on product labels before applicators can consider these strategies.

Figure 2. Kentucky bluegrass seeded same day of Dimension 2EW application (a); Kentucky bluegrass seeded 14 days after Dimension 2EW application (b); tall fescue seeded same day of Dimension 2EW application (c); tall fescue seeded 14 days after Dimension 2EW application (d). Photos taken six weeks after herbicide application in Manhattan, Kan.

The research says

- Seeding between 0 and 14 days after an application of Trimec Classic (2,4-D + MCPP + dicamba) or Drive 75 DF (quinclorac) has little or no effect on Kentucky bluegrass or tall fescue growth.

- SedgeHammer (halosulfuron-methyl) reduced turf cover when seeding was done between 0 and 14 DAT. This research supports waiting over 14 DAT before seeding Kentucky bluegrass or tall fescue after an application of this product.

- Manufacturers should consider updating recommendations on herbicide labels. Applicators can consider these strategies if product label guidelines are modified.

Literature cited

- BASF Professional and Specialty Solutions. 2014. Drive 75 DF herbicide specimen label. Retrieved from http://www.cdms.net/ldat/ld4BF000.pdf.

- Corteva Agriscience United States. 2015. Dimension 2EW herbicide specimen label. Retrieved from http://www.cdms.net/ldat/ld7ND001.pdf.

- Gowan Company. 2019. SedgeHammer herbicide specimen label. Retrieved from http://www.cdms.net/ldat/ld76P008.pdf.

- Huang, B., M. DaCosta and Y. Jiang. 2014. Research advances in mechanisms of turfgrass tolerance to abiotic stresses: From physiology to molecular biology. Critical Reviews in Plant Sciences 33(2-3):141-189 (https://doi.org/10.1080/07352689.2014.870411).

- McCalla, J.H., M.D. Richardson, D.E. Karcher and J.W. Boyd. 2004. Tolerance of seedling bermudagrass to postemergence herbicides. Crop Science 44(4):1330–1336 (https://doi.org/10.2135/ cropsci2004.1330).

- McFadden, D., J. Fry, S. Keeley, J. Hoyle and Z. Raudenbush. 2022. Establishment of Kentucky bluegrass and tall fescue seeded after herbicide application. Crop, Forage, & Turfgrass Management 8(1),e20151 (https://doi.org/10.1002/cft2.20151).

- Patton, A.J., J.M. Trappe, M.D. Richardson and E.K. Nelson. 2009. Herbicide tolerance on “Sea Spray” seashore paspalum seedlings. Applied Turfgrass Science 6(1):1-10 (https://doi.org/10.1094/ATS-2009-0720-01-RS).

- PBI-Gordon Corporation. 2017. Trimec Classic herbicide specimen label. Retrieved from http://www.cdms.net/ldat/ld2PP013.pdf.

- Senseman, S.A. 2007. Herbicide handbook, 9th edition. Lawrence: Weed Science Society of America

- Willis, J., J. Beam, W. Barker and S. Askew. 2006. Weed control options in spring-seeded tall fescue (Festuca arundinacea). Weed Technology 20(4):1040-1046.

Dani McFadden (dmcfadden@ksu.edu) is a graduate research assistant at Kansas State University, Manhattan, Kan.; Jack Fry is a professor of research and Extension specialist for Commercial Turf at Kansas State University; Steve Keeley is a professor of turfgrass teaching and research and department head, Horticulture and Natural Resources, at Kansas State University; Jared Hoyle is Midwest territory manager for Turf & Ornamental at Corteva Agriscience, Indianapolis; and Zane Raudenbush is a turf and herbicide specialist in the Davey Institute, Kent, Ohio.