A management style focused on cultivating positive connections within the workplace produces committed, creative employees who find their jobs rewarding, which can ease some of the pressure felt by the superintendent and elevate the quality of the golf course. Photo by Montana Pritchard

According to GCSAA survey data, the average golf course budget increased just 5 percent from 2010 to 2015. Despite this relative stagnation, golfer and employer expectations have continued to grow, and today’s superintendent also faces heightened pressure in the form of tougher environmental scrutiny, lack of an adequate labor pool, and decline in golfer participation.

Superintendents have long demonstrated ingenuity in dealing with higher expectations and limited resources, and I believe today’s superintendents will be successful in tackling future challenges. Developing an understanding of and placing greater emphasis on human connections in the workplace is a universally available strategy that can help any manager meet increasing demands. Qualities such as empathy, care and compassion are components of what’s known as the “positive human connection,” and when such virtues are displayed alongside strong leadership skills, managers can efficiently meet difficult organizational expectations, improve staff productivity, and even decrease the workplace pressure they feel on themselves.

Putting language to leadership in the workplace

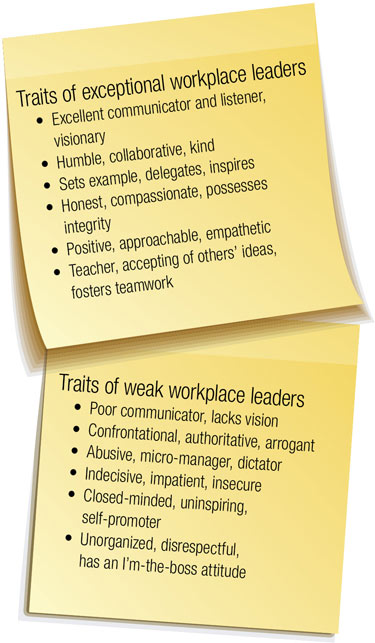

Last fall, as I was researching the concept of exceptional leadership, I asked more than 100 superintendents and co-workers to complete a survey that would document their opinions on what makes a strong workplace leader. For comparison, I also requested their thoughts on the traits of weak workplace leaders. I found the results (right) valuable and enlightening, and they support the notion that the positive human connection plays a significant role in effective leadership.

As a superintendent and manager myself, I reflected on each characteristic identified by my peers and colleagues, and on how well, throughout my 35-plus years on the job, I’d embodied the traits of the exceptional leader, and where I’d fallen short.

In retrospect, I could have been a better communicator and listener, been more open to others’ input, and better understood the value of meaningful criticism of my own performance. Perhaps most important, I could have focused more on being a teacher, trainer and delegator of responsibility. In my opinion, all golf course management professionals would benefit from doing an honest evaluation of their managerial demeanor against the attributes listed above.

Are you able to look a member of your crew in the eye and inspire that person to be a better employee? Are you a visionary? Someone your employees respect and admire? Are you humble, collaborative and kind?

Kindness — showing concern for others, valuing who they are, appreciating what they do, and expressing these sentiments to them — is a trait worthy of its own discussion. An exceptional leader improves morale, motivates staff, and gains trust and loyalty simply by being kind. Kindness gives rise to employees who feel valued and appreciated, and who in turn are more dedicated and work harder to accomplish organizational goals. Such returns from staff are cost-free and commonplace for the exceptional leader who nurtures positive human connections.

To understand how vital the positive human connection has become in the current workplace, I find it helpful to think back to the “good old days” — a time when my employees came to work expecting just a paycheck and hopefully job security. As anyone in the golf business knows, those days are gone forever. In the modern workplace, employees want and expect quality-of-life considerations, and the job itself is only part of their equation. While some managers may see this shift in employee desires as something negative, it holds promise for exceptional leaders who cultivate positive human connections, as they’re able to offer their team members an enjoyable and fulfilling work environment.

Conscious communication

I believe strongly in the saying “One cannot not communicate,” and as a supervisor, when you’re among employees or customers, you must always be “on.” During my years as a manager, I’d often overhear comments like, “What’s wrong with the boss today? I hope he isn’t mad at me.” Although I almost certainly had nothing related to one specific employee or situation on my mind, whenever my employees would see me, they would pick up on and internalize any nonverbal messages I was sending.

Communication can be verbal, nonverbal or visual, and it’s a two-way process involving the sender and receiver. The exceptional leader is cognizant of the different methods in which they may be communicating at a given moment, and is mindful of communicating accurately and whether their message is being received and understood. The receiver also has a responsibility in this “communication contract” to comprehend the information being conveyed, and, if necessary, to ask questions.

Author Dennis Lyon, CGCS (center) with two turf professionals he has mentored, Joe McCleary, CGCS (left) and Devin Mergl, at the Rocky Mountain GCSA Symposium in November. McCleary is the stormwater operations superintendent for the city of Aurora, Colo., and Mergl is the assistant superintendent at The Club at Flying Horse in Colorado Springs. Photo courtesy of Devin Mergl

A situation I encountered a few years back offers a good study in the importance of precise communication. A fellow superintendent had instructed his staff to occasionally skip the cleanup round on greens mowed with the triplex mower during periods of slower green growth, to avoid excess wear. The superintendent was very aware of the requirement to provide superior course conditions during club events, but he failed to communicate to employees never to forgo cleanup rounds in the lead-up to such events. The discord between the expectation and the instructions that had been communicated produced an undesirable, avoidable outcome. I recall similar missteps in my own career that stemmed from communication that wasn’t exact or thorough.

As mentioned, communication also involves accurately receiving information, and though superintendents can’t listen for their employees, they can guide them toward better habits. I once worked with a superintendent who, because he assumed he knew what I was going to say, would often stop listening partway through our conversations. Because of this, there would be times he wouldn’t follow the instructions he’d been given, although in his mind, he’d done exactly what he’d been told. My solution, in addition to emphasizing his responsibility to become a better listener, was to put important information for this employee in writing.

The micro- vs. the macro-manager

How one manages others reveals the value they place on positive human connections. In my view, there are essentially two types of managers: the micro-manager and the macro-manager.

The micro-manager is an autocratic leader. This person wields a my-way-or-the-highway attitude, and, in their opinion, they’re an expert in all things work-related. Communication is almost always top-down, and the only work accomplished by employees is that directed specifically by the micro-manager. This type of leader minimizes human connections and usually isn’t well liked or respected by employees.

The micro-manager does not delegate effectively, which results in the manager working endless hours while overall productivity remains below its potential. If you’ve ever worked for a micro-manager, you’re unfortunately familiar with the general misery bred by this style of leadership. In today’s work climate, the micro-manager stands little chance of sustained success.

On the other hand, the exceptional leader is a macro-manager and maximizes the benefits brought about by positive human connections. Such managers ensure employees understand and are committed to organizational goals, and give them the training, tools and flexibility they need to best fulfill their duties. The exceptional leader/macro-manager is quick to praise and handles discipline with compassion. Employee mistakes are viewed as a teaching tool.

The finished product is of more concern to the macro-manager than the process to get there, and because of this, the macro-manager empowers employees to come up with the best way to deliver the final results. The macro-manager delegates responsibilities, and employees are challenged to grow. Thanks to the power of positive human connections, the macro-manager typically has time to anticipate and prepare for future snags and difficult periods.

Employee empowerment: Exceptional leaders are strong teachers and delegators, and they allow their staff a say in processes, which boosts the ownership that team members feel toward the finished product. Photo by Montana Pritchard

An example of effective macro-management that has resonated with me was that of an assistant superintendent named Steve. One day, as the manager of golf for the city’s multiple courses, I asked Steve how often fairways were mowed at his course, to which he responded that he didn’t know. I was initially surprised by this answer, but Steve went on to say that if I wanted to know the frequency of fairway mowing, I should check with Frank, the fairway mower. I did, and Frank explained that fairways were mowed as needed, the frequency depending on time of year and where the fairways were located. Frank said his goal was to guarantee that “his fairways” provided outstanding playing conditions every day.

Steve was an ideal manager for Frank. Frank knew the objective was superior fairway conditions, and he had the training and resources to make it happen. Steve was totally committed to the mission of providing superior fairway conditions, but as a macro-manager, he left the decisions on how that was to be achieved up to Frank. If a fairway needed mowing twice per week, that’s how often it would get mowed. If, at times during the year, a fairway needed to be mowed twice per day, that’s the attention Frank would give it. As a result, the course’s fairways were pristine, and no one was more committed to furnishing top-quality fairway conditions than Frank.

The superintendent’s charge is to create an efficient, productive golf course operation. Focusing on positive human connections in the workplace will no doubt help one emerge as the exceptional leader necessary for success in today’s challenging work environment. As ancient Chinese philosopher Lao Tzu said, “A leader is best when people barely know he exists; when his work is done, his aim fulfilled, they will say: We did it ourselves.” (Or, in the case of Frank and his fairways, “He did it himself.”)

Dennis Lyon, CGCS, is a past president of GCSAA and has been a Certified Golf Course Superintendent since 1979. He earned a bachelor’s degree in horticulture from Colorado State University and a master’s in management from the University of Northern Colorado. Dennis spent 37 years as the manager of golf for the city of Aurora, Colo. A 44-year member of GCSAA, Dennis has received the association’s Col. John Morley Distinguished Service Award and the USGA Green Section Award. He is currently retired and a freelance writer, among other pursuits.