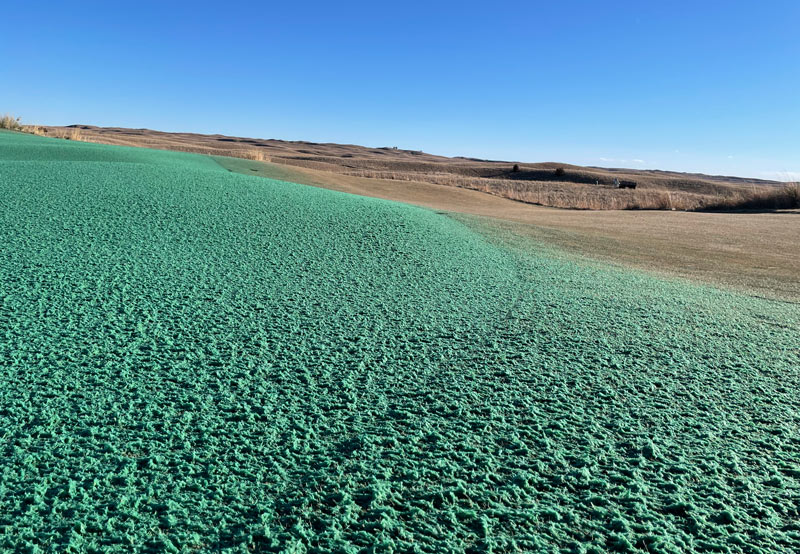

A cloak of hydromulch applied to the first green of the Dunes Course at The Prairie Club in Valentine, Neb., on Dec. 29, 2021. Photos courtesy of Andrew Getty

The same combination of geology and climate that makes The Prairie Club such a striking destination for in-season golf also makes keeping its greens alive in the offseason quite the challenge.

“Wind-swept” might be a great, bucolic way to describe The Prairie Club’s Dunes Course, in particular, when the American links-style course — designed by Tom Lehman and Chris Brands — is open. When it’s closed, however, that same sweeping wind, all too familiar to anyone who has ventured into the Great Plains in the frigid winter months, can really do a number on turfgrass.

For nearly each of the 11 years since The Prairie Club opened in Valentine, Neb., in the north-central part of the state, the golf course maintenance crew has combated Husker State bluster with an unusual ground cover: hydromulch.

“With so much acreage and all the open areas and the higher expectations, the mulch serves as an insurance policy,” says Andrew Getty, GSCAA Class A superintendent and a seven-year association member who is in his first year as superintendent on the Dunes Course.

Getty came to The Prairie Club — a 46-hole resort carved amid the Nebraska Sandhills that’s more than 300 miles from the nearest big city, Lincoln, Neb. — from across town. At the 10-hole Frederick Peak Golf Club, a municipal course in Valentine also designed by Lehman and Brands that opened in 2017, Getty could keep the substantially smaller greens healthy through the offseason through sand topdressing and watering.

But at The Prairie Club in general, and on its Dunes Course specifically, upkeep of the T-1/Alpha creeping bentgrass greens is a different story.

“Purely what (the hydromulch) does is prevent desiccation,” says DJ Shallenberger, superintendent on the Graham Marsh-designed Pines Course at The Prairie Club and a six-year GCSAA member. “It has nothing to do with green-up in the spring. It simply prevents drying out — winter desiccation.”

While superintendents at some northern courses use greens covers — essentially, tarps — for fall protection, that wasn’t really an option at The Prairie Club.

“The great thing the mulch does for us is, it’s permeable,” Getty says. “When we water, it still allows the greens to take moisture and retain it. The advantage for us is, we don’t have a lot of extra shop space. This way, we don’t have to worry about storing covers, and we don’t really have to worry about the wind getting under it and blowing it 70 miles away.”

Much ado about mulch: “The cold, dry days of January and February can be stressful, and the mulch provides us with a layer of protection that allows us to prepare for spring with confidence,” Dunes Course superintendent Andrew Getty says. Shown is the Dunes Course’s 12th green under hydromulch on Dec. 29, 2021.

Hydromulching is similar to hydroseeding, but, as the names suggest, they differ in the makeup of the slurry that’s slung. The U.S. Department of Agriculture says the terms are often used interchangeably, but hydromulching is the application of a slurry of water, wood fiber mulch and a tackifier without seed in the slurry. The practice can be used to combat soil erosion.

On about 30 greens at The Prairie Club, it’s used to prevent winterkill.

“Typically for us, all fall builds toward this,” Getty says of the late-fall/early-winter hydromulching.

Usually around Thanksgiving, the crews blow out the irrigation system, then apply snow mold fungicide to all the greens. Once the fungicide is down, they wait for a stretch of days with temperatures in the 40s, no snow and relatively calm winds.

“The trickiest part is operating our truck,” Getty says. “We have to drive through some native areas to get to some of the greens. It helps if the ground is frozen. It doesn’t have to be frozen, but it helps.”

The crews use a straight-sided, 3,000-gallon tanker truck purchased about three years ago from the retired owner of a nearby seed company.

“The club used to rent it every winter,” Shallenberger says. “We knew he was retiring, and we wanted to be the first to purchase the truck. It’s instrumental in the process.”

Top: The 3,000-gallon tanker truck, purchased by The Prairie Club from the retired owner of a nearby seed business, holds enough hydromulch to cover 2 to 2½ of the Dunes Course’s larger greens per truckload. About 30 of the holes at the 46-hole facility receive a hydromulch buffer for winter. Bottom: The 11th green on the Dunes Course gets hosed with hydromulch on Dec. 29, 2021.

A crew of two or, ideally, three applies the slurry — water, wood fiber mulch and FlocLoc, a flocculating soil stabilizer — via a 200-foot fire hose.

“It’s not an exact science,” Getty says. “I estimate we put down around a quarter inch of mulch — just enough to cover the green completely. We might go a little thicker on the mounds, and some of the protected greens might be a little thinner. The key is just coverage.”

Editor’s note: With just a brief window to bring greens out of long, harsh winters, a Canadian club has fine-tuned a custom cover system that shields turf from the elements without creating anoxic conditions. Read more in Perfecting winter putting green protection.

Through experience, The Prairie Club crews have found the most effective way to apply the hydromulch is to start at the farthest point on the green from the truck and work backward, shooting the slurry through a flat fan nozzle into the air and letting it fall like rain onto the greens. All 18 holes on The Dunes get the hydromulch treatment, while only 10 or so on The Pines — which is protected from the prairie winds from the Snake River canyon rim and the prevalent ponderosa pines — are mulched.

When applied, the hydromulch is bright green to aid the applicator in determining coverage (Getty refers to it as “painting”), but the exposed hydromulch dries to a light tan color relatively quickly.

The teams can cover 2 or 2½ of The Dunes’ larger greens per tankful and empty about three tanks per day. Weather permitting, they can mulch all 30 greens in a little more than a week.

“That fire hose can kick your butt if you let it,” Getty says with a laugh. “But, no, it’s not too bad.”

Top: Watering the eighth green over the top of the hydromulch in February 2021. Bottom: The ninth green in February 2021, with the remains of snowfall visible atop the hydromulch.

The spring removal process is another matter.

The Prairie Club is usually closed from mid-October until early May. By mid-March, the crews are keeping an especially close eye on the weather in order to get the mulch off the greens before they start to grow.

“That might be the longest week out here. It’s not the most fun part of the process,” Getty says.

“A week? More like two and a half,” Shallenberger counters with a chuckle.

The fire hoses make a return for the cleanup process. Using the courses’ frost-free hydrants and 2-inch outlets, crews attach the hoses and get to work, blowing the mulch to the side of each green, where it’s left to dry. The process takes four to five hours per green. Shallenberger says the teams typically spend 180 to 200 hours in spring just cleaning the greens.

“We’ve found what makes it more difficult is if the green has sand on it, whether from topdressing or when the wind blows sand from the bunkers onto the greens,” Getty says, noting that’s why the crew ends its every-two-weeks topdressing program in October.

Right: A patch of turf in March 2021, just before the crew removed the hydromulch from the entire green. The photo gives an idea of the mulch’s thickness. Visible are the top layer of hydromulch, tan from sun exposure; the lower layer of hydromulch, which remained bright green; and the healthy turf beneath the hydromulch, lightly dusted with wind-blown sand.

Collecting the dried mulch in the back of turf utility vehicles takes far less time than the cleaning of the greens.

“You just try to find a calm day so it doesn’t blow out of your cart,” Shallenberger says. “Just scoop it into the back of a ProGator and find a place for it on the property. We try to utilize some of it along the maintenance cart paths that are wind-eroded. We try to recycle a little bit.”

Part of what makes the hydromulch so time-consuming to remove is what makes it so attractive for the blustery winter months: its perseverance. The two superintendents estimate the 30 holes amount to 9 to 10 acres of greens. Unlike covers, which can be uprooted by strong winds, the hydromulch sticks.

“Last year, after we applied in mid-December, we did have a strong wind front for three days — sustained winds of 70 mph for 10 hours. It was a long night,” Getty says. “We lost a little around the edges, but not much. Maybe 10%.”

The Dunes Course’s fifth green immediately after the hydromulch was washed off in March 2021. Maverick, superintendent Andrew Getty’s 3-year-old golden retriever, inspected the results.

Shallenberger wrestled with greens covers at a previous course, and he considers the roughly $6,000 spent yearly on the hydromulch to make far more sense financially — and practically.

“It’s been a while since I looked at the cost of greens covers,” he says, “but it would cost a lot to use greens covers on these same greens, with the acreage of them. And we do not have the shop space to store them. That would take a big part of the shop just to store them.”

Andrew Hartsock is GCM’s managing editor.