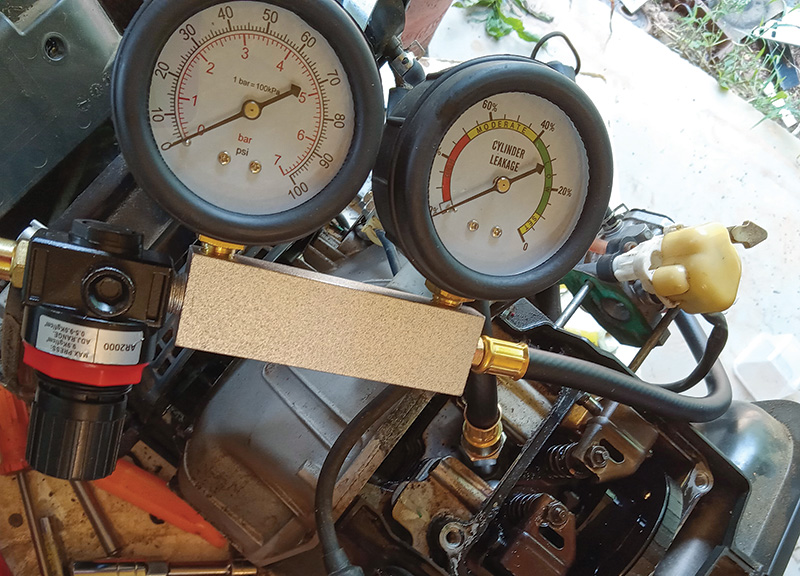

An inexpensive leak-down testing kit worked to determine it was end of the line for a Honda generator that suffered from too-long oil change intervals and overheating. This photo was taken after testing, in which 50 pounds per square inch input pressure showed about 70% cylinder leakage from a minor exhaust valve leak and worn piston rings. The diagnosis was confirmed by a teardown afterward. Photo by Scott Nesbitt

Engine leak-down tests can help spot internal engine problems before they go too far. You need an air compressor, some patience, maybe a helper and a test kit usually available for under $50. The test applies to all internal combustion engines, from tiny

string trimmers to massive diesels.

The concept is simple. Pump air at a known pressure into a top-dead-center combustion chamber, then measure how much pressure the chamber holds. The difference in readings gives you the percentage leak-down.

You’ll need to prevent the crankshaft from turning, resisting 100 pounds per square inch normally used to test automotive gasoline engines.

Diesel engines are typically tested at 200 psi. Small two-cycle and four-cycle engines might need only 50 psi. You don’t always need maximum pressure or the strongest helper to get results.

Some test results are obvious. Bad head gaskets produce bubbles in the cooling system; bad valves produce hissing noises. Also obvious is that air will come pouring out the dipstick tube and other crankcase openings. That’s normal. No piston makes

a perfect seal. There’s always leakage into the crankcase. But how much is too much?

Service manuals likely won’t help. You’ll find specifications are given for compression tests that involve spinning the engine, but not for the leak-down test during which the engine remains still. Various online forums, education sites and

YouTube videos provide some guidance. My test gauges say 10% to 40% is good. Diesel people want 30% or less. Race engine builders aim for 5% or less, after modifying a stock engine that’s OK with 20% to 30%.

In a perfect world, you would test each new engine after break-in, and again as it ages to develop a baseline for comparison with future tests. Short of a tear-down, this leakage test data can be the best available check on an engine’s internal

health. This assumes testing is done on a sensible regular basis, like every 250 hours or after a certain number of oil changes.

The data trend is more important than the raw numbers. Increased leakage increases odds that sludge is starting to harden and glue the rings to the pistons. More leakage means more blowby, more sludge, more oil consumption, less compression, less power,

worse fuel economy … it’s called the death spiral.

Sludge formation is retarded by engine oil additives, but those are eventually used up. Changing the oil restores the protection, and frequent oil changes are known to greatly extend engine life.

Once the ring-binding problem is spotted, you can try changing the oil more often, hoping for improvement. Testing will tell if that is working. You can also try a sludge-buster treatment, while being fully aware there’s a lot of snake oil on the

market. I personally have had decent results using sludge removers offered by some major, legitimate engine-chemical companies. These typically involve large quantities of chemicals and a daylong sequence of steps to clean, flush and clean again.

Ultimately, it’s easier to run tests, write down the results and trust the gauges.

Scott R. Nesbitt is a freelance writer and former GCSAA staff member. He lives in Cleveland, Ga.