In Massachusetts’ environmentally sensitive Cape Cod region, Matthew Crowther, CGCS, has kept golf courses thriving for 25-plus years. This bunker edge at Cape Cod Country Club has a few clumps of bluestem. Most of the course’s bunkers aren’t mowed and are left to grow wild. Bluestem is a colonizing plant in among the fescues. Photo by Randi Baird

Joan Malkin checked her email inbox. One new message in particular made her smile.

The person who’d hit the send button on that email hadn’t seen Malkin in more than a year, but the gesture could be viewed as typical of Matthew Crowther, CGCS, a good steward who never ceases to connect with and look out for others, as Malkin and many others have come to know.

Crowther has been the golf course superintendent at Cape Cod Country Club in East Falmouth, Mass., since 2019. Previously, he oversaw nine-hole Mink Meadows Golf Club in Vineyard Haven, Mass., on Martha’s Vineyard, for more than two decades. That’s where he met Malkin. Not only did she play regularly at Mink Meadows, but she also helped author fertilizer-use regulations for the island’s boards of health (the island has multiple boards) and the Martha’s Vineyard Commission, a 16-member group that has broad jurisdiction for planning and reviews developments of regional impact on the island. There’s no doubt that Crowther made a lasting impression on Malkin for orchestrating the kind of environmental harmony that was demanded.

“He was great. Conscientious. A mindful steward of his golf course. And prideful, I might say,” Malkin says.

You can also say this about Crowther: He is the recipient of GCSAA’s 2021 President’s Award for Environmental Stewardship. The award was established in 1991 to recognize “an exceptional environmental contribution to the game of golf — a contribution that further exemplifies the golf course superintendent’s image as a steward of the land.”

Crowther changes a hole location on the ninth hole at Cape Cod Country Club in East Falmouth, Mass. Photo by Randi Baird

“Matthew is widely recognized as one of the true shining stars in our industry — a genuine environmental steward whose work at both Mink Meadows Golf Club and now at Cape Cod Country Club are worthy of praise,” says GCSAA President John R. Fulling Jr. “His accomplishments deserve to be held up as examples of the golf industry doing the right thing when it comes to the environment.”

No doubt this one is special to Crowther. “I’m truly blown away by the award and damn proud of it,” the 30-year GCSAA member says.

A mentor ... and Jimmy Stewart

The star of the holiday movie “It’s a Wonderful Life” reminds Crowther of the individual who helped him establish his own wonderful life in the golf industry.

A native of the old mill town of Coventry, R.I., Crowther went to the University of Rhode Island with designs on a career as a landscape architect. Instead of accepting student aid, Crowther paid tuition by participating in a work-study program under the guidance of industry legend C. Richard Skogley, assisting Skogley on turf plots and research. “He had a Midwestern charm about him. He kind of reminded me of (actor) Jimmy Stewart,” Crowther says. “At the time, I didn’t know the difference between an oak tree and an elm tree, or turfgrass management.”

By the time he was a junior, Crowther was well aware that he was facing a crossroads: either follow through on a major in landscape architecture, or enter the turfgrass management program.

A drawing class, one of his electives that semester, was among the deciding factors. “I befriended a kid whose dad was an architect,” Crowther says. “My drawings looked like they came from a third grader. His looked like a Picasso.”

Undoubtedly, the Skogley factor also heavily swayed Crowther. An educator and turfgrass breeder (as a researcher, he produced several turfgrass cultivars, including Providence creeping bentgrass), Skogley was the recipient of the USGA Green Section Award in 1992. “The man was an influence on the entire industry,” Crowther says. “He suggested I give this turf thing a try.”

Hello, turf world

The journey began 11 miles outside of Boston.

That’s where Crowther landed his first job after college, working six seasons at Pine Brook Country Club in Weston, Mass. It was a relatively brief stay compared with his next adventure, which launched in 1995 when Crowther became the superintendent at Mink Meadows, often a playground for the rich and famous (Presidents Bill Clinton and Barack Obama played there occasionally).

Lambert — “Bert” — was Crowther’s second Labrador retriever at Mink Meadows Golf Club in Vineyard Haven, Mass. (Thumper was the first). Crowther says both were well loved on the property and the beach. Photo courtesy of Matthew Crowther

His first day at Mink Meadows, though, was delayed. Crowther’s father, James Rodney Crowther, passed away soon after he had accepted the position. The father had introduced the son to growing things. “He had a green thumb, grew oranges year-round as a child. My grandfather (Earl Everett Crowther) taught my father how to enjoy planting and growing things,” says Crowther, noting that his grandfather received a citation for his work on the fire-suppression system used during the development of the atomic bomb.

From his first day on the clock at Mink Meadows, Crowther was driven to succeed. Fear played a part in that. “I was afraid of not having the course be as good as it possibly could be,” says Crowther.

He was also keenly aware of the environmental aspect of working on Martha’s Vineyard. Mink Meadows was founded with great care to preserve the property while keeping the ecological community intact. When managing Mink Meadows, Crowther focused on using as few inputs as possible. He worked with 45 acres of irrigated turf, but only 3½ acres were conventionally maintained with fertilizers and pesticides. All practices and programs were designed and structured to create healthy, quality playing surfaces with the environment in mind.

He also thought before he acted. Crowther describes it as a “wait-and-see, laid-back” approach. Only when it was necessary would he consider fertilizers and pesticides, in order to reduce the amount of chemicals being applied at the facility. Was he conservative in his approach? You bet. “We applied wall-to-wall for grub control only three times while I was there,” he says.

Before and after images of a tallgrass area at Mink Meadows Golf Club where colonizing pine trees were pervasive and ubiquitous. They survived mowing, and, instead of spraying herbicide, Crowther chose to hand-pull them.

As part of a large salt marsh project during Crowther’s time at Mink Meadows, part of the course was used to dispose of the soils pulled from the marsh. Salt-laden soils were capped with native material and reseeded as a pollinator habitat. Photos courtesy of Matthew Crowther

At Mink Meadows, non-irrigated native areas were implemented to improve water conservation, reduce mowing and minimize chemical inputs on the course. When establishing low-maintenance native areas, Crowther made sure to keep ecological corridors for the wildlife using native grasses and forbs while maintaining the property’s playability for golfers. Along with the benefits realized by those native areas, the use of existing soils on the property minimized exposure to disease, reduced costs and limited the energy consumption associated with maintaining those areas.

According to Lianne Larson, the GCSAA Class A superintendent at White Cliffs Country Club in Plymouth, Mass., Crowther was a leader in tackling the environmental aspect of their jobs. “Matty is a good superintendent. Always thinking. He was more environmental-conscious way before it became the norm,” says Larson, a 28-year GCSAA member. “He’s a guy I could call any time. He was kind of a pioneer.”

Worth the risk

Chuck Bramhall remembers Crowther as being among the first in line and willing to take chances.

As a vendor for Eco-Soil Systems, Bramhall introduced Crowther to the company’s Bioject Biological Management System in 1998, which featured a refrigerated storage unit. Inside was Tx-1, a dollar spot suppresser developed by Joe Vargas, Ph.D., and his co-workers at Michigan State University. According to an article by Pete Dernoeden, Ph.D., the unit possessed a cleaning mechanism and a UV light filter to kill most bacteria entering the system from a potable water source. After two seasons of a preventive fungicide program, Crowther opted to replace that method for his fairways with Bioject.

Right: Bioject, a refrigerated storage unit that dispensed a dollar spot suppressor, was employed for fairways at Mink Meadows Golf Club beginning in 1998. Photo by Matthew Crowther

“He (Crowther) was one of the first in the area to look at it. And he was one of those that hung in there with it when he had it,” says Bramhall, now a territory manager for Harrell’s. “Matt’s always been careful, tried to do the right thing fertility-wise and plant protectant-wise. The first topic of

conversation with him was about how he could do the job and still lessen the environmental aspect.”

Because of Crowther’s integrated pest management plan, fungicide was not applied to fairways for the remainder of his time at Mink Meadows. In addition, insecticide applications on fairways and roughs for the control of white grubs, which are common in New England, were rarely done. Instead, Crowther tolerated the slight damage from skunks and crows digging for the grubs over insecticide applications.

Bill Coulter, CGCS, looks back impressed on what Crowther has achieved. “Bioject fell out of favor with a lot of people, but Matt stuck with it and didn’t use fungicides. I think it worked out to his advantage,” says Coulter, a 23-year GCSAA member at Montaup Country Club in Portsmouth, R.I. “He had a beautiful piece of property that was conducive to do those things in an area where it’s environmentally sensitive and a hot-button issue. What he did was always something I admired.”

New sod on the face of this bunker was harvested from an out-of-play area at Cape Cod Country Club with a similar growing environment to the area around this bunker — mainly, no irrigation — which should increase its chances of survival and will look more natural than commercial sod.

Soil moisture meters have been crucial to Crowther’s efforts at Cape Cod Country Club since he arrived at the facility in 2019. Photos by Randi Baird

In retrospect, Crowther is convinced the use of Bioject was worth taking a chance on. “I decided I was going to jump on it,” Crowther says. “I started with one machine and injected it in the irrigation system every day. We added a second machine and did that procedure of running a syringe cycle as soon as it got dark for many years. I then moved to spraying it through a conventional sprayer.”

Think of it as switching from daily preventive injections through irrigation to a curative application through a sprayer. “We got crushed by dollar spot every year, but Bioject worked where we sprayed it. It was labor-intensive, but after fertilizer regulations came along, more geared toward nitrogen, I was able to convert to an all-liquid program easily. I worked with the group that wrote the regulations, and using a slow-release liquid fertilizer in the tank with the Bioject satisfied the regulations,” he says.

Cape Cod Country Club: A new challenge

He may have worked on an island, but no way has Crowther remained isolated from representing his industry.

Crowther was president of the New England Regional Turfgrass Foundation in 2015-16 and still serves on its board along with colleagues such as Mark Richard, CGCS. That service has provided him with a couple of come-full-circle moments. “After my freshman year in college, I spent the summer working for Mark at Potowomut Golf Club (in East Greenwich, R.I.),” says Crowther, who recalls not raking one of the bunkers there because turtles had laid eggs in it. Twenty years ago at Mink Meadows, Crowther roped off a dirt parking lot after turtles had laid eggs there.

Editor’s note: A Georgia golf club has rescued thousands of diamondback terrapin hatchlings from its bunkers. Learn more about the initiative (with video) in Turtle power: Georgia golf club hatches diamondback terrapins.

In 2007 and 2008, Crowther was president of the GCSA of Cape Cod. Through his leadership, he created positive change for the organization and environmental stewardship nationwide. He has been a panelist at the Golf Industry Show for a program titled “Successful Low-Input Turf Management: Is it Practical?” Crowther has also traveled to GCSAA headquarters in Lawrence, Kan., on numerous occasions as a Chapter Delegate.

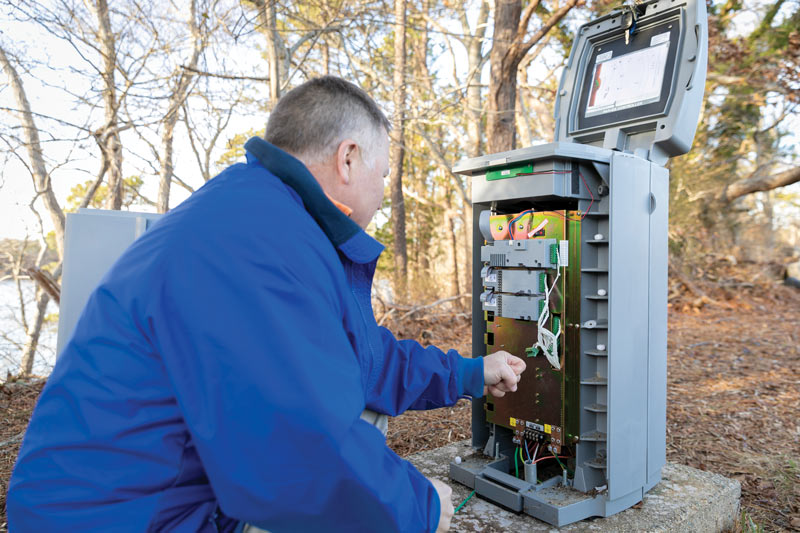

Irrigation satellite stations are integral to water management at Cape Cod Country Club, Crowther says, adding that understanding how to use and repair the components of the system are the cornerstone to proper water conservation.

Crowther chats with Cape Cod Country Club equipment technician Mike Marin. Photos by Randi Baird

Nowadays, Crowther is encountering new challenges at Cape Cod CC, including the presence of water bodies. The prospects motivate him.

“You try to have the same mentality, but this is a different animal. I’m still trying to figure the place out,” he says. “We had some turf-conditioning issues. We’ve brought some turf back, greens and tee surrounds. They look great.

“Do we still need to be environmentally sound? Even more so. Three holes border an irrigation lake where we draw water from. I have water on the golf course, if you will, and draw from that water. At Mink Meadows, I had no water on the golf course. Here, at the 18th hole, a pond is right up against it. At the ninth hole, you literally play around a pond. Anything you put into the ground has the potential to go into the water. You have to keep that in mind in any of your practices. It’s an asset to be near water, but it’s also a big responsibility.”

At home, Crowther’s wife, Cheryl (they have a son, Josh), handles the turf. “She loves mowing grass. Always has,” he says. When it comes to what happens at Cape Cod CC, Crowther proudly handles the role of being a devoted steward of the premises. Anybody who knows him wouldn’t expect anything less.

“Coming here was like a reset button. I want the place as good as it can be, to be as environmentally sound as I can, and do the job right and prove I can do it on an 18-hole course,” Crowther says. “I want to leave the place with a better infrastructure than I inherited. As superintendent, your job is to work with nature and protect the asset for the players and owners. I believe all superintendents are environmental stewards.”

Howard Richman is GCM’s associate editor.