The vermicomposting bins at North Shore Country Club in Glenview, Ill. Photos courtesy of Shehbaz Singh

The grounds crew at North Shore Country Club (NSCC) in Glenview, Ill. always goes in circles for efficient golf course management. But that does not mean we just walk in circles for course maintenance! Dan Dinelli, CGCS, and the grounds team at NSCC follow

the concept of "circular economy" to maintain aesthetic value, agronomics, playability, pest resistance, low maintenance costs and environmental stewardship.

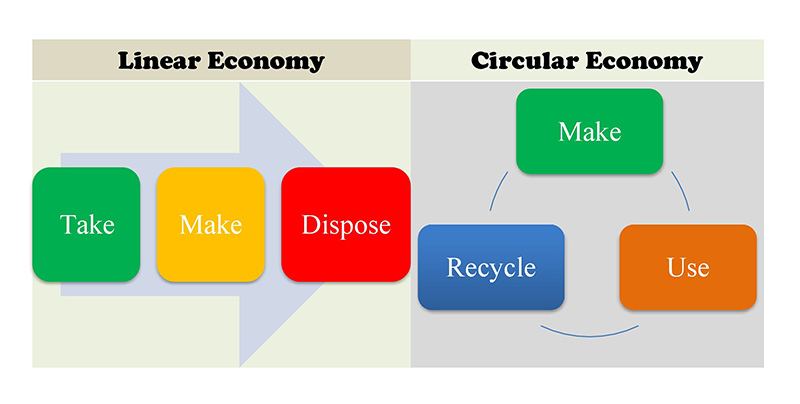

Circular economy promotes the reuse of natural resources, homogenizing businesses, natural ecosystems, everyday life and waste management. By reusing resources with minimal processing, a circular economy reduces the chasm between production and ecosystem

health. A linear economy, by contrast, disposes of products developed from raw natural resources after a single use (fig. 1). A circular economy can play a vital role in managing golf courses efficiently in today's world where natural resources are

becoming limited day-by-day, but standards are still high.

Fig. 1. An illustration of a circular economy.

I joined NSCC as an assistant-in-training after finishing my master's degree in turfgrass science from Oklahoma State University. My experience has exposed me to a wide range of sustainable practices in golf course management. Dan Dinelli’s broad

golf course maintenance vision and motivation assures a quality experience for club members. The NSCC maintenance team not utilizes innovative methods to meet their goals of providing a healthy golf environment. What inspired me most was seeing the

ways the team tries to replenish the ecosystem in each decision they make. I learned there are different ways golf course superintendents can contribute to a circular economy while maintaining the aesthetic and playability standards of a premier golf

facility.

Circular economy as it relates to the water cycle is paramount due to the current global freshwater crisis. Water is one of the most vital resources for maintaining plant health and playability on the golf course. The average golf course uses about 300,000

gallons of water per day (Audubon International). This need presents a challenge for superintendents to seek efficient and sustainable water management practices.

NSCC uses the circular economy approach of reduce, recycle to capture stormwater and reuse it for irrigation on the golf course. Stormwater is diverted to an underground storage tank using the course’s existing drainage system. The underground tank

(fig. 2) is located on the south side of 18th hole fairway and has a capacity of 473,000 gallons, essentially serving as a giant rain barrel. Captured water is then gravity-fed to onsite ponds, where it is used to irrigate the golf course.

Fig. 2. Stormwater storage at North Shore Country Club.

With this approach, NSCC saves money by lowering the energy required to pump groundwater. The holding ponds are also planted with wetland vegetation to improve water quality. Although water reuse may not be a necessity for golf courses in Illinois right

now, NSCC’s philosophy is that it's better to start early than late. NSCC also employs the 'reduced water use' approach of circular economy, utilizing practices that minimize their irrigation footprint.

In the summer, hydrophobic soil leads to localized dry spots on fine turf. Grounds team members at NSCC hand water these spots instead of using the in-ground sprinkler system, reducing water wasted on areas with optimal soil moisture (evaluated using

handheld soil moisture meters), while enhancing uniform playability of the green. NSCC also collaborates with Cale Bigelow of Purdue University and Derek Settle of the Chicago District Golf Association to host onsite soil surfactant trials for potential

use on hydrophobic soils in bentgrass greens.

Jerry Dinelli (Irrigation specialist, NSCC) avoids using the sprinkler system during high winds whenever possible, which helps reduce evaporation and non-target application. The crew also incorporates a mixture of sand + biochar + vermicompost in greens

with a DryJect machine. Biochar is known for its potential as a soil amendment with positive water-retaining properties. We have not calculated the direct reduction in water requirements from this practice but believe continued use will help reduce

water requirements in high percent sand-based rootzones.

One issue for large cities like Chicago is managing sewage water and sludge waste. NSCC plays an important role in the circular economy by reusing treated sewage waste on their fairways. This treated waste is scientifically referred to as "Biosolids.”

Biosolids are part of natural life cycle and have soil amendment properties which make them advantageous for sustainable crop production. For decades, treated sewage sludge was used in agricultural and horticultural industries as a fertilizer and

soil conditioner. Direct use of sewage sludge poses some environmental and human risk if it contains disease-causing organisms (e.g., viruses, bacteria, fungi etc.), heavy metals (e.g., lead) and toxic chemicals. However, decades of research have

resulted in treated forms of biosolids that are safe for agricultural use.

The Metropolitan Water Reclamation District of Greater Chicago (MWRD) produces approximately 150,000 dry tons of biosolids per year. Approximately 10% of the biosolids produced by MWRD are classified as Class A biosolids, the highest category assigned

by the Environmental Protection Agency. These biosolids have virtually undetectable pathogen levels and the material also complies with strict standards regarding heavy metals, odors, and pest attraction. North Shore Country Club has used Class A

biosolids for last 20 years as a fertilizer/soil amendment for all fairways on the golf course (fig. 3).

Fig. 3. Biosolids being distributed as a fertilizer and soil amendment.

Dan Dinelli believes years of biosolid application has enhanced soil microbial population, improved nutrient availability, soil physical and chemical properties, reduced thatch layer and reduced pest susceptibility at NSCC. The grounds crew has not applied

any synthetic fertilizer on fairways and roughs turfgrass since starting the biosolids program. This practice has also reduced fairway maintenance cost by not spending money for fertilizer. Another added benefit: NSCC receives MWRD’s biosolids

for free!

Dan Dinelli believes biosolids also help maintain the playability of the course through improved soil physical properties. Core aerification creates a temporary reduction in the aesthetics and playability of the course, inconveniencing players. Using

biosolids as an organic amendment/soil amendment reduces thatch accumulation, which in turn reduces the need for periodic aerification.

A surprising thing I learned at NSCC was the vermicompost system developed by the grounds crew (fig. 4) to broaden sustainability efforts and reduce food waste. This system takes food waste (barring meat and dairy products) from the clubhouse kitchen

and delivers it to be consumed by earthworms. In turn, the earthworms excrete a rich compost and fertilizer in their "castings.” Vermicompost contains not only earthworm castings but also bedding materials and organic wastes at various stages

of decomposition. This material is used as organic amendment for greens, reducing the waste stream while improving soil function and plant health.

Since microbial growth is important to successful vermicomposting, the carbon to nitrogen (C:N) ratio of the mix must be considered. Carbon provides energy for microbial growth, while nitrogen provides the building blocks for cell structure. Just as with

conventional composting, the (C:N) ratio by weight should be around 30 to 1.

Fig. 4. NSCC's vermicomposting bins at work.

NSCC also utilizes spent grain from local breweries (fig. 5) for compost production and for colonizing Trichoderma fungi. Spent grains is the insoluble part of barley grain left over in the process of beer making. This brewery waste is rich in fiber and

proteins. Trichoderma is a beneficial fungus which can act as a biological control of various turfgrass roots’ fungal diseases. Trichoderma efficently establishes itself in turfgrass rhizosphere and can even overwinter on roots during Illinois’

cold weather. This biological product is available in market under the trade name of Bio-Trek 22G, but it’s also possible to grow your own Trichoderma fungal population.

Fig. 5. Bins of spent brewery grain, ready to use for compost production.

NSCC also takes yard waste, which mainly constitutes leaves from on-course trees and municipal leaf cleanup, and uses spent grain inoculated with Trichoderma fungi to decompose it (fig. 6). With this two-in-one approach, we get compost rich in nutrients,

along with Trichoderma for turfgrass disease control and thatch reduction. This composted material is the parent material for compost tea/extract used on our greens for soil health and bentgrass disease suppression. Dan Dinelli believes this practice

saves money in our annual budget and creates a healthy soil environment for greens, in addition to helping our locality reduce waste.

Fig. 6. Compost and spent grain combined for turfgrass disease control and soil nutrients.

I never thought managing golf courses could be such exciting and thoughtful work. I will never look at a course the same way. Meeting the course’s high standards while replenishing the natural ecosystem is not an easy job. As stewards of Mother

Nature, however, we’re responsible for managing and efficiently using natural resources. The NSCC grounds team believe in three R's of circular economy: reduce, recycle and reuse. Reduce the wastage or overuse of natural resources as much you

can, recycle the used natural resources for potential use, and reuse the waste to replenish natural ecosystems.

Shehbaz Singh is an assistant superintendent at North Shore Country Club in Glenview, Ill., and the manager of Turfgrass research at the Chicago District Golf Association.