Turf students getting the basics on grass types and root systems in the classroom. Photo by William Ames

In Jared Diamond’s “Collapse: How Societies Choose to Fail or Succeed,” the author examines ancient civilizations that flourished and then died out. The pattern that he observed was that ancient civilizations (think Mayans or Mesopotamians)

collapsed within about 10 years of reaching the peak of their economic and social power. The same pattern is eerily familiar to those of us who have been in the turfgrass research and education field long enough to have gray hair.

As a graduate student in turfgrass science at the University of Illinois, my advisors, Al Turgeon, Ph.D., and Dave Wehner, worked closely with golf course superintendents and other turf managers to raise money for research support through golf days, trade

shows and other events. Superintendents and others in the turf industry including sod producers, landscapers and athletic field managers contributed to the cause. Other agriculture groups — i.e., corn or soybean farmers — didn’t

appear to dig into their own pockets to support research. State support of agriculture programs largely funded these operations.

After graduate school, I went to Michigan State University where I met Gordon LaFontaine of the Michigan Turfgrass Foundation (MTF), which raised money to support turf research. LaFontaine was an exceptional businessman and fundraiser. MSU’s turf

program was and is generously supported by the annual fundraising and the MTF’s significant endowment. When I returned to the University of Illinois in 1995, the Illinois Turfgrass Foundation (ITF) provided similar support that funded research,

also supporting work at Southern Illinois University, which then had a turf program.

From approximately 1990-2007, golf course construction boomed. Students came to large land-grant universities like Michigan State, Penn State, Ohio State, Purdue, Iowa State, North Carolina State and others in record numbers. New turf faculty were hired,

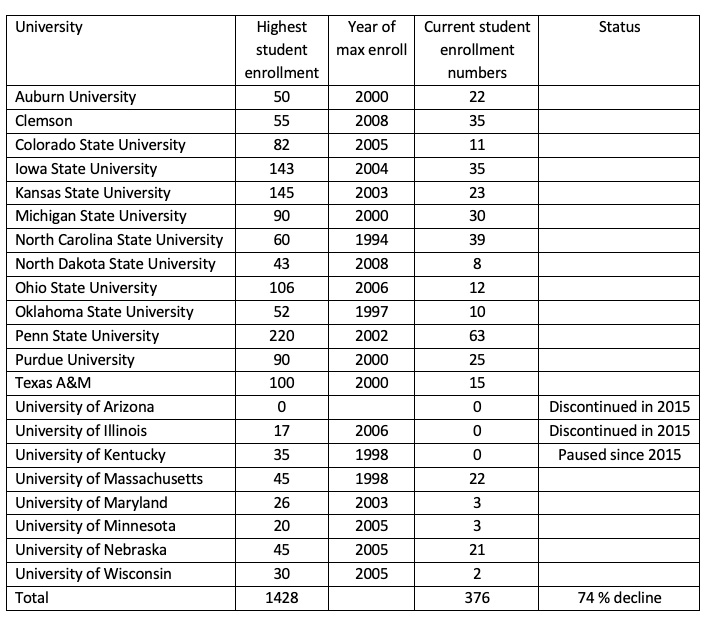

funding was flush, and the industry showed exceptional growth. From my viewpoint, the peak arrived in the early 2000s, when turf majors at Iowa State reached a high of 143 (Table 1).

Table 1. Historic turfgrass student enrollments and current student numbers.(Not all Universities with turf programs are represented. Missing programs are either an oversight or did not respond to a data request.)

The turning point

Everything began to change in 2008, beginning with the Great Recession. The golf course industry had overbuilt, and more golf courses were closing than opening. Job prospects went from great to dismal. Students looking for their first job competed against

candidates with years of experience, or former superintendents willing to take an assistant’s job after their previous employer closed.

Enrollments in turf programs declined across the country. Iowa State’s enrollment is now around 35 students. Even bigger drops have occurred at other land grant universities (Table 1). When enrollment at Illinois dropped to near zero in 2014, my

department dropped our turfgrass course offerings, effectively shuttering the program. The University of Arizona ended their turf program in 2015, with the University of Kentucky pausing theirs around the same time.

A multi-decade decline in state funding has also affected turfgrass programs at land grant universities. State support has flipped completely from 40 years ago, with 85-90% of our budget coming from tuition and other revenues, and only about 10% from

the state. Once truly public universities have become semi-private schools, with budget decisions driven by tuition and research dollars. At the University of Illinois, tuition and fees have gone from $1,074 per year in 1982 to over $18,000 per year

in 2020. Throw in housing, meals, and books, and you’re up to $30,000 per year. A college degree is valuable, but you’ll need a high-paying career to cover those costs.

Where will future superintendents and other turf professionals be trained? As faculty with a turfgrass emphasis retire, they are not replaced. In the early 2000s, the University of Illinois had five faculty focused on turfgrass research and education.

Today it’s one, soon to be none. On our campus, the rule of thumb is each faculty member should be supported by 30 undergraduates. By that metric, two to three turf faculty would require 60-90 undergraduate turf majors.

Field days have lost some relevance but still offer the opportunity to see new research in person. Photo by Darrell J. Pehr

Where do we go from here?

What does the future hold for turfgrass education and research? Clearly, students are key to maintaining faculty presence at universities. Universities try to attract the best students regardless of where they live. In 1980 at University of Illinois,

97% of undergraduate students were from Illinois, and less than 1% were international students. In the fall of 2021, 72% of the students were from Illinois, and 14% were international students. Out-of-state tuition is typically about double that of

in-state tuition, and there is a surcharge for international students.

Because of declining state funding, universities recruit more out-of-state and international students to generate tuition dollars and increase student quality by drawing from a larger pool of applicants. Public land-grant universities attract the best

students from around the world and train them for high-paying careers in computing, engineering and business. It’s not surprising turfgrass enrollments are going down as entrance requirements have gone up.

As an educator, I believe in the value of a four-year degree. I’ve also encountered many excellent superintendents who graduated from two-year degree programs. These programs offer good value, since they are half as long and generally offer lower

tuition. However, I’ve also noticed that many of our four-year turf program graduates start in the golf course industry, but later go into other related careers. A four-year degree helps students more easily pursue advanced degrees that allow

them professional flexibility. Many superintendents also work at private clubs, where a four-year degree may improve their perceived level of professionalism to members.

How can we make the degree process more affordable? First, I would encourage interested students to attend a community college to take care of general education requirements, with the intent of transferring to a four-year university. Two years at community

college can satisfy the math, general science and humanities courses required by most schools.

Another alternative to a four-year degree is a short-course program, such as those at Michigan State, Penn State, Rutgers, North Carolina State and the University of Massachusetts. These programs vary in length from 10 weeks to two years and offer students

exposure to world-class faculty and facilities. Online programs are another option. Penn State University’s World Campus has led the way in the development of an online turfgrass curriculum.

Finally, cultivating more state and national scholarship programs for students who complete a two-year degree would be ideal. Substantial scholarships of $5,000-10,000 would attract students to careers in turf management and encourage them to complete

a specialized program. By making a dent in rising tuition expenses, universities can keep cultivating a diverse student body and talent pool.

Student awards at the 1998 Illinois Turf Conference when the program had five faculty working in turfgrass research, teaching, and extension. Photo courtesy of Bruce Branham

Turfgrass research

Most universities with turfgrass research and education programs are major research institutions, meaning that capturing research funding is an important part of a faculty member’s role. Research is expensive. So is maintaining a research facility

that can duplicate golf course turf. Equipment costs and maintenance, irrigation systems, specialized soils, fertilizers, pesticides and skilled management are required for realistic turf research.

As a researcher, much of my funding came from contract research. A company would request a proposal to test a product, fertilizer, pesticide or cultural practice, and I would provide information on what it would cost for us to do that research. What I

and my fellow researchers charge for this research often does not reflect the value and cost embedded in these research sites.

Turf researchers see the value of replacing a departing faculty member with someone similarly trained. However, a university provost must weigh returns on that investment. Another faculty member in computer science, for instance, can mean additional undergraduate

students and potential grants from the National Science Foundation, Department of Education, and others that pay full overhead and can range from $1 million all the way to $10 million. Those numbers can be tough to compete with.

One factor that can help is strong, consistent support of turfgrass programs at the state level. Michigan State is an excellent example of how a dedicated turfgrass organization can build a significant endowment that continues to fund research and student

scholarships. Developing personal relationships with department heads and college administration can also help keep a program vibrant. We need industry leadership to keep these state-level organizations vibrant and engaged.

Events like GCSAA's annual turf bowl competition allow students to put their knowledge to work and learn from experts in the field.Photo by Roger Billings

Putting it all together

How do we as an industry work to secure continuing turfgrass education and research? Having a robust turfgrass research and education infrastructure in the U.S. may mean better support for fewer programs. Some attrition has already occurred (Table 1),

but we’ll continue to struggle to support all the programs listed. Below are five ideas for ensuring the continued existence of turfgrass research and education programs in universities in the U.S. Remember, undergraduate students drive faculty

numbers. Consistently having 20-plus undergraduate turf students will ensure at least one faculty position at most universities.

1) National leadership and cooperation. The USGA has a competitive research program that’s supported many turfgrass research projects at U.S. universities. Similarly, GCSAA supports research through several programs, including the

GCSAA Foundation. More resources from other groups are also available. Pooling resources and talents will result in a more-coordinated, concentrated, and substantial approach to research funding.

2) Support for historically strong programs. As previously mentioned, Michigan State’s program is a good example of this. Rutgers has a strong breeding program. North Carolina State and Clemson have strong industry support. Penn

State also has a rich tradition. These programs and others like them need continued support, both locally and nationally, to retain the faculty positions they currently have. Alumni and local support are critical to keep these programs vibrant and

visible to administrators. Support at the state level encourages support at the national level.

3) Scholarships. Scholarship programs enable students to attend four-year universities. Targeting third- and fourth-year students with significant scholarship amounts may ensure career interest while encouraging a more affordable junior

college route.

4) Fundraising. Endowments are great and can be useful, but it takes very large endowments to generate significant support for scholarships and resources. A million-dollar endowment provides only about $40,000 per year. A better approach

may be quasi-endowments, in which both the interest and principal are expended so at the end of designated period, no funds remain. A million-dollar quasi-endowment with a 15-year life span would provide slightly more than $100,000 each year at an

annual rate of return of 6%, or two-and-a-half times the same amount put into a traditional endowment. A 15-year time frame is long enough to ensure significant research projects along with undergraduate and graduate student training.

5) Recruitment. Working on a golf course as a high school student is the pathway that has led most current superintendents into the profession. Young children may grow up wanting to be an astronaut, doctor or lawyer, but only youngsters

whose mom or dad were superintendents even know managing a golf course is a profession. Creative local-level programs can attract more high school students to explore the field through hands-on experience.

Because of the large number of students from the 1990s and early 2000s, there are many mid-career superintendents. They all know how difficult it is to find newly trained assistant superintendents. What happens to the industry in a decade when that cohort

begins retiring? Maintaining the status quo will lead to continued erosion of the last 40 years of progress.

Turf research and education barely existed prior to the 1960s. It will take a coordinated effort at both the state and national levels to maintain excellence in turfgrass education and research and keep history from repeating itself. Technology is changing

rapidly and will significantly impact how golf courses are maintained. In a few years, drone sprayers, robotic mowers and other autonomous tools will be common on golf courses. These advances will only increase the skills needed by future turf managers.

Bruce Branham is a professor and faculty extension specialist at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign