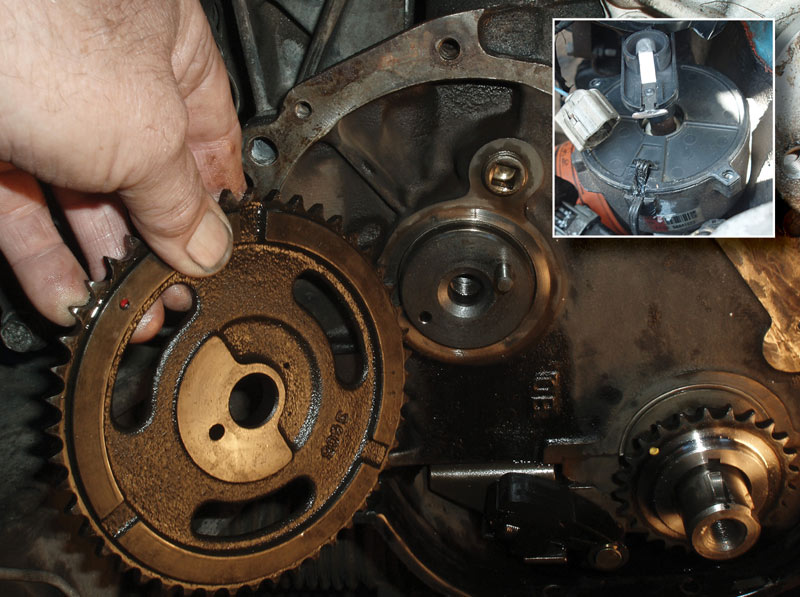

The factory installed this camshaft dowel pin in the wrong hole, putting the sprocket 180 degrees out of position. Pointing the distributor rotor to the No. 1 cylinder position (inset) verified the error, as did checking the positions of that cylinder’s intake and exhaust valves. Photos by Scott R. Nesbitt

Technicians tend to assume that the people who make machines and repair parts know what they’re doing. The following episode emphasized, for me, the need to verify rather than trusting, and to reason your way through unwanted surprises.

It started with a simple timing chain replacement on a 2.5-liter, four-cylinder gasoline engine that has been in production for 30 years. It’s an ancient design — a cast-iron block and head with push rods and rocker arms. A timing chain sprocket on the crankshaft rotates the camshaft sprocket at half the speed of the crankshaft.

The teenaged pickup had only a quarter-million miles. The factory paint on the timing chain cover was intact, indicating this would be the first timing chain replacement. What could go wrong?

After removing pulleys and the timing chain cover, we trusted that we’d simply remove the sprockets and timing chain and install the new parts. The only trick was to make sure the alignment marks — a small dot on each sprocket — were lined up when installing the new sprockets and chain. All four-cycle engines use such marks, whether they’re a simple two-sprocket system or an engine with several sprockets for multiple overhead camshafts, balance shafts, and water and oil pumps.

Surprise! The timing mark on our camshaft sprocket was 180 degrees off. Somehow, the factory had installed a camshaft with the positions of the small and large pin holes at the sprocket end of the camshaft reversed. The dowel pin in the larger hole mates with a hole in the sprocket, creating yet another alignment point. Camshafts are made on computer-controlled machines. Somehow, the computer had messed up. On the assembly line, someone had turned the sprocket 180 degrees, mounted it on the camshaft, and sent the engine on its way.

The engine was running before surgery. We had followed normal procedure and rotated the engine to align the distributor rotor with the No. 1 spark plug position (inset photo, above). The distributor is gear-driven off the camshaft, which provided yet another point to verify that the camshaft lobes were in the right orientation. We pulled the valve cover to double-verify that the No. 1 cylinder valves were in the all-up “firing” position. Pulling the valve cover to check valve position would be required on newer engines that use magnetic sensors to check camshaft and crankshaft positions and distribute computer-controlled spark.

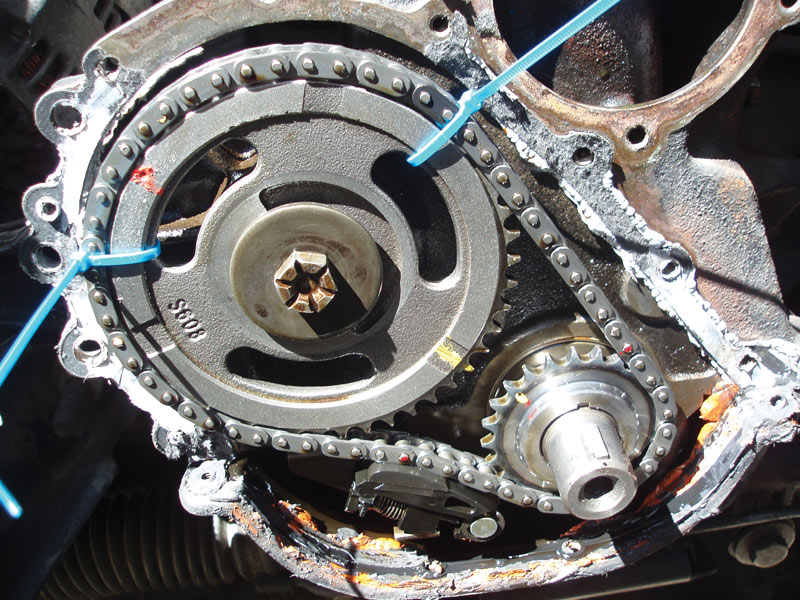

A new yellow camshaft sprocket timing mark, opposite the red-marked factory dot, provides proper sprocket alignment on the mismade camshaft. Zip ties temporarily held the chain to the sprocket to ease installation. This shot was taken during disassembly to install the new camshaft.

We marked the factory timing dots in red, and painted on new white marks to show the actual sprocket alignment needed to let the engine run. Zip ties held the chain to the sprocket during installation. The new timing chain and sprockets improved the engine’s performance, although a month later, we installed a new camshaft, hydraulic lifters and a reconditioned cylinder head in hopes of pushing the old truck to the half-million-mile mark.

The timing chain incident reinforced the importance of verifying. During the same week, two string trimmers and a power blower would start, but wouldn’t throttle up. Pouring the fuel mix into a glass jar and letting it sit overnight resulted in a layer of water settling to the bottom — the problem was water in the non-ethanol gasoline we use for two-cycle engines. Who can you trust?

If there’s a lesson here, it’s that when things don’t go as expected with a repair job, adopt paranoia instead of panic. Verify instead of assuming that suppliers and original-equipment sources always get things right.

Scott R. Nesbitt is a freelance writer and former GCSAA staff member. He lives in Cleveland, Ga.