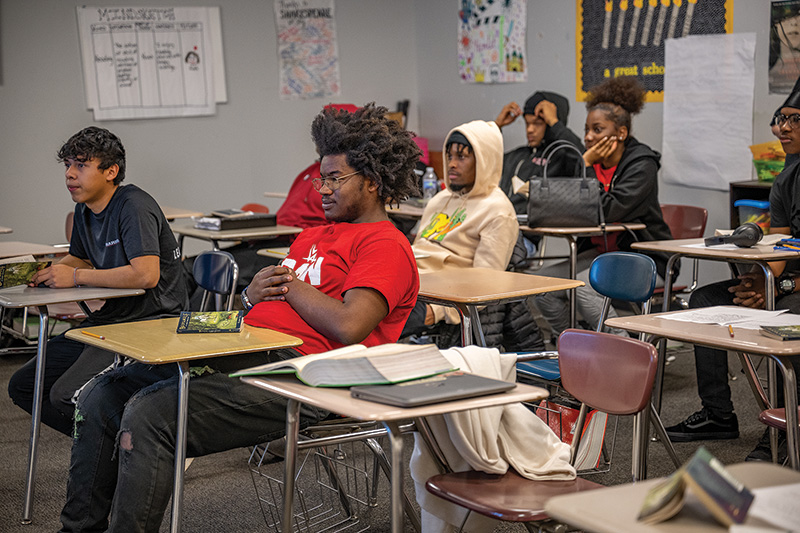

Textron Specialized Vehicles' RPM program combines job training and education with an instructional day incorporated with a $10 an hour four-hour shift. Photos by Brent Cline.

There was no need for Denym Free to ask his mother, Tyronza, for help, seek a bank loan or check out Autotrader.com. When he wanted to buy a car, Free took ownership of the situation.

Three letters — RPM — were a key to his drive.

“It showed me if you do the right things, it can change your life,” Free says.

Free graduated from high school in 2022, in part because of his participation in RPM, which stands for Reaching Potential Through Manufacturing. The program is a public-private partnership between Textron Specialized Vehicles — the manufacturer of E-Z-GO golf cars, Cushman utility vehicles and Jacobsen turf equipment— and the Richmond County School System based in Augusta, Ga.

While he was attending Hephzibah (Ga.) High School, Free supplemented his graduation requirements through RPM. The program combines an instructional day with a $10 an hour four-hour shift in manufacturing at a facility that is half schoolhouse, half manufacturing plant.

The facility includes classrooms and educational space to allow students to make progress toward their high school degree and earn valuable paid work experience. Students produce components and subassemblies for products manufactured by Textron, Richmond County’s largest industrial employer with a workforce exceeding 1,700 in Augusta. The company manufactures E-Z-GO golf cars and Cushman utility vehicles at its Augusta facilities.

Students apply for admission to RPM and are selected for participation by Richmond County School System officials. Potential students are evaluated on multiple factors, including lack of progress toward a high school diploma, absenteeism and their personal situations. They may live below the poverty level, be homeless, or already be teen parents, as just some examples of circumstances of some RPM students.

A welder for Textron, Free is one of more than 300 students who have graduated from RPM and one of more than 100 who have gone on to full-time employment at Textron Specialized Vehicles. Others have been hired at an array of companies. Free has found a home at Textron. “There’s a better chance you can’t get into trouble when you’re working and going to school at the same time,” Free says.

What a ride it’s been for him. Free bought his own car, a gray 2019 Dodge Charger, before he turned 19. “It showed me what can happen if you do the right things,” he says.

Free is an example of what is right about RPM. “As our people look to retire, we could replace them with students. We have created our own pipeline with them,” says Derek Wynns, director of GSE operations for Textron Specialized Vehicles, who oversaw the RPM program until a recent job change within the company. “For me, it’s rewarding to see young people like Denym gain a skill they can carry the rest of their lives. It’s the greatest reward, very fulfilling. That’s what we’re supposed to do as leaders, take people to the next level.”

RPM student Areonna Harold at work during a recent shift at RPM.

Setting the stage

Jason Moore was on the clock.

A longtime educator including stints as a school principal and science teacher, among other things, Moore already had a handle on how to develop future leaders. He taught students how to become problem solvers and gather evidence to support their conclusions. When he was hired later to oversee a brand new initiative, there was only one acceptable conclusion.

Textron Specialized Vehicles and the Richmond County School System announced the creation of the RPM program in January 2016. Moore, RPM principal, and his team had seven months to get the program up and running because school was to start in August.

“In my first presentation that year, I asked the question, ‘What’s the backup plan?’ They told me there is no backup. I said, ‘What if the kids come in, they make parts that don’t work, do we shut the lines down?’ They said, ‘There is no backup plan,”’ Moore says.

OK, got it, Moore thought. He knew there was no need to jump to conclusions — just a goal centered on a slew of happy endings. He would not let Textron down. “We didn’t want to shut the lines down. We can’t shut the lines down,” Moore says of his thinking at that pivotal moment for RPM.

Jason Moore is principal of RPM for the Richmond County (Ga.) School System.

Textron and Richmond County School System embraced an already-proven model to guide the development of RPM. In fact, the road map was just down the road. Southwire, a leading manufacturer of wire and cable used in the transmission of electricity that is based in Carrollton, Ga., started 12 For Life in 2007.

Carroll County, Ga.’s graduation rate needed a boost from hovering at 64%, meaning that only one out of every three students starting the first grade that year would not go on to graduate. Since Southwire’s employment opportunities require candidates with either a diploma or GED, Southwire devised strategies to reverse this trend in collaboration with Carroll County schools.

This partnership spawned the 12 for Life program, which serves the community by providing opportunity, education and employment for at-risk youth, emphasizing that education opens doors to success. Like RPM, 12 for Life combines traditional classroom instruction with jobs inside a modified Southwire manufacturing environment. Students earn wages for their work and, most importantly, learn skills they will need after graduation. At one time, all five high schools in the Carroll County School System achieved a graduation rate of 90% or higher and a total district graduation rate over 91%. 12 For Life now also incorporates schools in Florence, Ala.

“I knew of Southwire. I was at a conference once and saw their presentation. When I met with Textron staff and they said, ‘Hey, there’s a program we would like to model here in Augusta,… ’ and I was like, ‘I know this.’ I knew what Southwire had done and the progress they had made in their community,” says Moore, whose responsibilities include site supervision, staffing, student instruction and public relations.

That knowledge gave Moore a head start when Textron and the Richmond School System decided to move forward. Still, Moore realized it wasn’t going to be a breeze. “When you recruit the kids with the worst attendance and have to turn it around, that’s a challenge,” he says.

Students study “Beowulf” in English class at the RPM facility.

Off and running

When RPM debuted in the summer of 2016, it took less than 48 hours to see something special was happening.

Teachers were in place. So were the first 75 students. “I think that first day, the school side of it was easy,” Moore says. “I wondered what was going to happen when they got on the (manufacturing) floor. The students went first to training sessions. I think it was day two they started running the machines. The kids just picked it up. They started making parts and getting after it. Kids are pretty quick when you show them what to do. It was a little stressful that day, but it was exciting to watch.”

The students’ demeanor and confidence grew daily. Those who stayed with RPM and showed up all the time rather than skipping a day here or there were hooked.

“When the kids started, they weren’t successful in school because they had low self-esteem. Now, they can say, ‘I came into RPM and started making brake cables. My supervisors said they look good, quality was met, and I picked up my own paycheck.’ It was that self-efficacy,” Moore says. “Once the kids get that, now we find they start showing up every day. They keep coming back because they like the work.

“From the time those students get here to the time they leave … just to see how they hold themselves differently is special. It’s very rewarding, and you can really see the results of your efforts. You come every day, you have a good attitude, listen to your supervisors, you’re going to make a paycheck, and you start to see that success. It’s a joy to see that they’re starting to put it together.”

They certainly do put it together. Those golf cars and utility vehicles built in Augusta feature parts built by RPM students. The students’ handiwork is on E-Z-GO and Cushman vehicles being used all over the world.

“Imagine what would happen if they had a program like this in every community? That would be powerful,” Moore says. “What if we had 1,000 RPMs? That’s the next step. We needed a pipeline. RPM provided that. We think it can be replicated.”

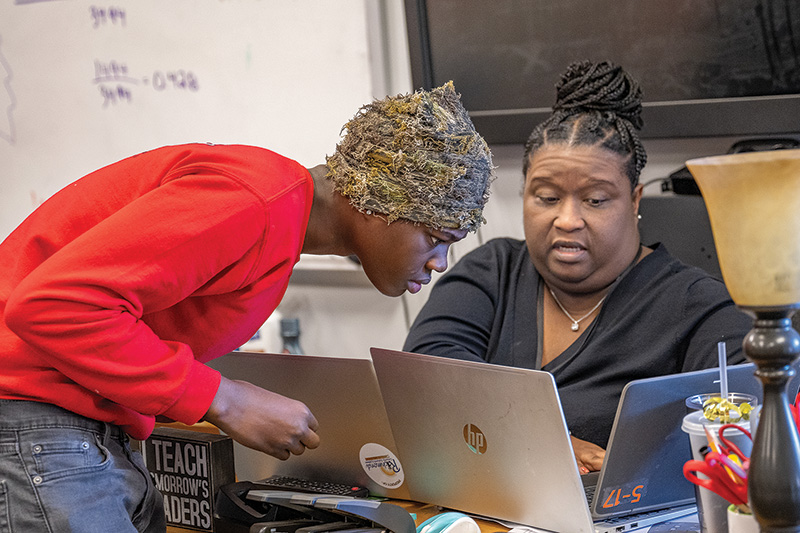

Adrianne Bogans, Ph.D., RPM assistant principal, assists student Elijah Green during math class.

Onward

Janiya McKinnie dropped out of T.W. Josey High School in Augusta her junior year.

The COVID-19 pandemic had thrown her for a loop, as it did others in schools across the nation who struggled to make that classroom-to-online transition. It overwhelmed McKinnie, so she decided to take a break. In the meantime, she wanted to find a job, which proved to be another hurdle.

“I couldn’t find anything. Not in fast food. Not at Walmart. Some places you had to have a diploma. It was very frustrating,” she says.

Her mother, Tosha, took matters into her own hands. “She signed me up for RPM,” McKinnie says.

About one-third of RPM graduates go on to work for Textron. McKinnie’s story is one of many that resonate with Phillip Bowman, director of assembly operations, Textron Specialized Vehicles.

Students at work on the manufacturing floor during a shift at the facility in Augusta, Ga.

“It (RPM) may very well be one of the programs nearest and dearest to my heart. It impacts lives of individuals who may have challenges in their way,” Bowman says. “To see the growth, the maturation, the accountability in their lives, is really impactful from a leadership standpoint. Lives and communities are impacted by the effort the students put into it.”

In January, McKinnie was a member of the class that pushed RPM above 300 graduates. She was asked by the administration to participate in the graduation ceremony to turn the tassels from the right side to the left side of the others who were graduating. Her diploma also meant that McKinnie completed what she had started at T.W. Josey High at a time life threw her a curveball.

Meanwhile, she has been in the process of finding a job. She also is considering going back to school. McKinnie has saved up money she made while working at Textron during school and is interested in pursuing criminal justice or child development.

McKinnie’s personal development is a sight to behold. A journey that once upon a time was stalled and at a crossroads now is all about forward progress, which allows her to dream big.

RPM has done its part to make her dreams come true.

“Before, I never believed in second chances,” McKinnie says. “Finally, I can see there is a thing called second chances.”

Howard Richman (hrichman@gcsaa.org) is GCM’s associate editor.