A bunker project at Kennett Square (Pa.) G&CC showcased the value of strong relationships between golf course architect, builder and superintendent. Pictured here are architect Paul Albanese, along with superintendent Paul Stead and some of the crew. Photo by Brad Klein

The definition of solid leadership often goes off on rambling tangents, counter to society’s waning attention span. Notwithstanding, at its most effective core, leadership is best summed up as the ability to achieve results through people.

Some posit that technology drives success. To others, conversely, it’s ostensibly an enabler that optimizes efficiencies. After all, who designed, developed and manufactured technology? Well, people did.

While some bad apples emit negative energy and influence, there are indeed more good souls in this world who have their eyes on building prized outcomes based on common goals.

Every golf project’s superpower — from initial ideation and bid process through completion — is clear, concise and transparent communication. The thesis postulates that well-defined, desired project results, with each group leveraging

its expertise as early in the project life cycle as possible, serve as a solid foundation for success. Unfortunately, when one party falls short in that area, it risks dragging down others that could lead to a mission not accomplished.

Developing and constructing golf courses, whether from scratch or as a renovation, is hardly immune to the trap of personalities superseding progress and quality at large. The common stereotypes are that architects are egotists, construction companies

wallow in worker-bee perceptions, and superintendents are territorial. The triangulation could get even more complex if course owners — the real risk-takers — detect the players aren’t, well, playing nicely in the sand trap.

So, what can those players do to overcome the potential of a bursting level of strife?

“Get buttoned up,” says Jake Riekstins, chief development officer of Landscapes Unlimited and a 23-year GCSAA member. “A thoughtful and inclusive review of construction feasibility with all external stakeholders (builders, architects,

designers, consultants) and internal stakeholders (owners, members, department heads) will flesh out challenges and barriers to achieve quality, budget and schedule adherences. In this exercise, bad news early is good news.”

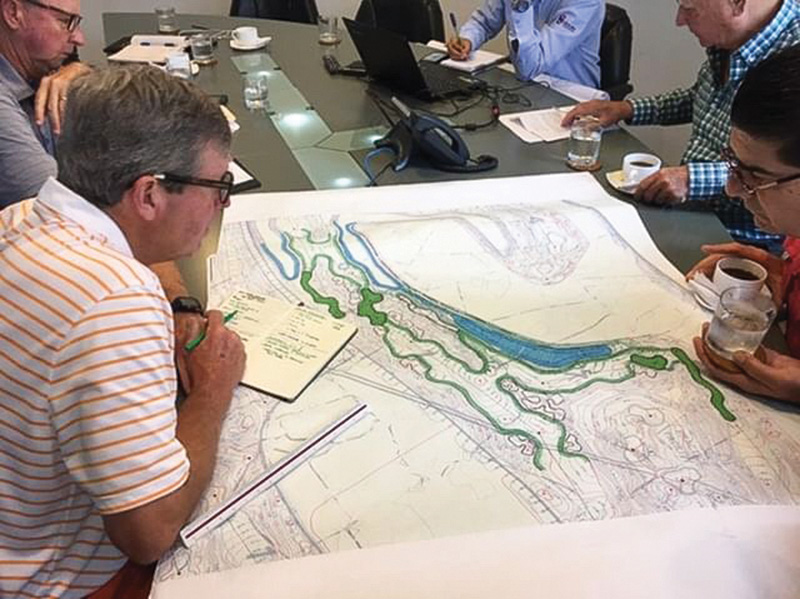

Bruce Charlton, a member of the American Society of Golf Course Architects, reviews plans for the new design at Guayaquil Country Club in Ecuador. Photos courtesy of Bruce Charlton

Begin with the end in mind

Landscapes Unlimited is big on modern-day best management and executionary practices. They all start, continue and finish with a complete understanding of project scope, stakeholders’ expectations and the property at large. Without that basis from

the outset, the devils in the details — especially if not understood early in the costing phase — will inevitably bubble up in the execution phase.

Riekstins is steadfast about everyone being armed with the same intimate knowledge. From the builder’s seat:

•Complete understanding of scope informs labor, equipment, material, spatial and permitting requirements to perform the work safely and reliably. Scope and the aforementioned resources inform schedule and milestones and suggest workarounds. A review of

risks to schedule includes supply chain dynamics and pricing volatility, weather and other delays within and beyond control of the architect, construction company and superintendent.

•Complete understanding of expectations from the course owner serves to empower and align all parties as project partners to deliver on time and on budget. Regular updates to the schedule and budget numbers and a firm cadence of team meetings minimize

surprises. Remember, bad news early is good news because there is time for the team to pull together and right a listing ship.

•Complete understanding of the property highlights quantifies and qualifies a host of key factors for any project — material storage yards; lay-down areas; access/egress and circulation around the property for deliveries and haul-off; areas of disruption

and those to remain untouched; existing conditions, such as rock, soils, water, water table, wetlands; and installed or future utilities and utility locations, including irrigation water source.

Nodding in agreement to all that is Justin Apel, executive director of the Golf Course Builders Association of America, who believes all parties vital to high-performing teams should be onboarded from the project’s start, not staggered. This guards

against unnecessary delays in labor shortages, H-2B work visas and materials deliveries with ample time for correction in the event that what’s uncontrollable goes sideways.

“Stretch the dollar with a kickoff site inspection that identifies trouble areas,” Apel says. “The whole team should be involved because many minds create best solutions.”

Forrest Richardson, a past president of the American Society of Golf Course Architects, is on the same page and says relying on contemporary tools to streamline communications, promote collaboration and ultimately enhance product output is key.

“We’ve heard for years that detailed plans can get in the way of good golf design,” he says. “The wisdom being that, ‘We always need to make changes in the field.’ While I agree, it’s obvious that the future will

rely more and more on technology, where the vision of the golf course architect can be highly specific and quantified in various digital formats. Whether it’s drone fly-throughs or integrating machinery with our plans, we are bound to see technology

bridge the gap between what we want and how we get there.”

The virtues of technology aside, superintendents rarely forget designing and constructing golf courses is part art, part science. They’re also taught that, at its nucleus, it’s a business in which people derive profit or eat loss.

“How to lay out and construct a world-class course, relatively speaking, with a continuous eye on fiscal responsibility, is the million-dollar question,” says Bryan Bielecki, vice president of agronomy for Indigo Sports, a Troon company. “It

all starts with recognizing there are milestones to achieve, and, assuming each party pulls its weight in close collaboration with others, the effect will be spectacular.

“How would you like it if the general contractor didn’t get along with electricians and it becomes a Hail Mary to get your kitchen remodel complete on budget and on time without consternation? Put yourself in the course owner’s shoes.”

Bielecki continues by noting that courses and corresponding budgets should be built with golfer demographics foremost in mind. What’s the psychological, economic and cultural climate of the neighborhood or destination? Is this the only course in

town? Family orientation or pure, unadulterated golf? Predominantly hackers or better players? The list goes on and on and on, and everyone’s work is geared toward consumers who ultimately pay the bills.

“Be on the same page after considerable diligence,” Bielecki says, “and the odds of a revered and profitable course skyrocket.”

The saying, “Bad news early is good news,” has been proved time and time again in successful golf course construction and renovation projects where architect, builder and superintendent have forged strong relationships.

An open book

Course conditioning is typically the No. 1 attribute that drives golfers to play one course over another, and the design-and-build process holds meaningful impact on maintenance practices, efficiencies and the almighty dollar that, over time, could amount

to an easy seven figures.

Then there’s playability. If the architect builds a monument to himself or herself, then we might as well name the course “Lost Balls.” Vertical construction plays into consistency of look, feel and flow of member-guest experiences,

so clubhouse and building contractors join to from a quartet with architect, construction company and superintendent.

There are software programs, even as common and remedial as Google Docs, which update everyone in real time. If one person or company falls behind schedule or experiences budget overruns, everyone knows. Hiding and finger-pointing need not apply.

Matt Ceplo, CGCS, at Rockland Country Club outside New York City, agrees. He regularly posts a blog to keep members, guests and the community aware of evolving renovations. Taking it a step further, Ceplo advises conducting town hall meetings with all

parties involved in the design-build process. Drawings and photos are worth a thousand words, and often controllers and estimators are involved in communications to show how bills are responsibly rolling in. This mitigates a slew of inquiring e-mails,

texts and phone calls.

“Get out in front with organized messaging and sticking to blogs and town halls at regular cadences, perhaps a combination of the first of each month, every other month or quarterly,” says Ceplo, a 36-year GCSAA member. “The last thing

we want is for members to question our ability to shepherd their hard-earned money because they’re uninformed.”

Landscapes Unlimited’s Riekstins echoes Ceplo. “Accountability and communication are key to harmony. No one wants to let down the project or have anyone think they don’t have their eye on the ball.”

Golf course projects can produce big results, but they are disruptive for club members and loyal golfers. Strong lines of communication from architect, builder and superintendent to those key customers can smooth the waters.

Taking the high road

Several superintendents and construction managers point to Stanford University professor Robert I. Sutton and his New York Times bestselling book, “The No A**Hole Rule.” A must read, it’s the self-proclaimed “definitive guide to

working with — and surviving — bullies, creeps, jerks, tyrants, tormentors, despots, backstabbers, egomaniacs and all (others) who do their best to destroy you at work.”

It’s worth repeating that while these destructors are in the minority, they are present in the marketplace; we all likely know one or more. Equipping oneself to properly handle them spells the difference between misery and pleasantry, as well as

mitigating risk that causes extreme delays and shoddiness in projects’ quality levels.

“Listen and listen closely,” says Indigo Sports’ Bielecki. “Selfishly speaking, it’s amazing what you can learn from architects and builders to make you more well-rounded and propel your career. To be proficient in what makes

them tick and click is integral to taking pride in and enhancing your own performance.”

Those who crystallize strategic and tactical plans into writing have a definite leg up to become winners, Riekstins says. Relegating knowledge to one’s head is a sure-shot recipe for forgetfulness, especially during the hectic pace of a project

and among those who aren’t in the field every day.

Yes, as creators, we all like to see our visions come to fruition by getting our hands dirty in the field, but there’s desk work that can’t be pushed aside. There’s no way to circumvent it, so embrace it as a necessary skill and a path

toward working on even better projects. For example, the anticipation of learning how to use Excel and PowerPoint is much more daunting than reality.

Almost to a person, superintendents synopsize the importance of communications style and cooperation like this: While it should be inherent but is often overlooked, treat people like peers. They could be your bosses down the road, and they’ll undoubtedly

remember respect and disrespect like it’s yesterday.

Todd Styles is a freelance writer based in Reston, Va.