With a focus on providing real-world solutions for turfgrass managers, J. Bryan Unruh, Ph.D., serves as professor of environmental horticulture at the University of Florida’s West Florida Research and Education Center near Milton, Fla. Photos by Tyler Jones, University of Florida/Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences

When the University of Florida’s Dodge pickup truck eases to a stop under a brilliant blue northwest Florida sky, J. Bryan Unruh indulges in a moment of reflection.

“This was all cornfield in January of ’96,” he says, motioning to the tree-rimmed acres of neatly aligned, 80-foot-by-80-foot turfgrass research plots at the university’s West Florida Research and Education Center, near Milton,

Fla. Unruh, professor of environmental horticulture, has held a faculty position here since 1996 and has built a career that has had a profound impact on the establishment and practice of golf course maintenance with nature in mind.

That track record of insight, inspiration and implementation has been instrumental in building consensus and momentum in the effort to establish best management practices (BMPs) for golf courses across Florida initially and, now, across the country. Unruh’s

efforts over almost three decades led to his selection as recipient of GCSAA’s 2023 President’s Award for Environmental Stewardship.

Unruh, a 33-year association member, was not expecting a call from GCSAA President Kevin Breen in October 2022.

“Kevin called as I was doing a walk-through on our house under construction,” Unruh says. “The caller ID indicated it was from California, and I almost didn’t take the call, as I assumed it was a telemarketer. Upon answering, Kevin

congratulated me on being selected to receive the award, and I was speechless. I think I simply said, ‘Well, thank you.’ And then my mind was flooded with the ‘why me?’ thoughts. There are so many deserving people in this industry

that have contributed greatly — why did they choose me?”

West Florida Research and Education Center Turfgrass Science Technician Jayson Ging checks research plots at the center.

A growing interest in turfgrass

Unruh’s selection is the result of a passion for turfgrass science that stretches back to his first experience on a golf course in Kansas.

“At a very early age, I, like many kids, started mowing lawns to earn spending money. I continued this endeavor through high school but never intended turf management as a career; I desired to be an attorney,” Unruh says. “The time came

to enter college, and I had decided that the time necessary to earn a law degree was too long, and I really didn’t want a desk job — so I declared horticulture as my major at Kansas State University. Ironically, I was in school for 10.5

years and largely have a desk job today.”

While in college, he learned that most turf students pursued golf course management, so Unruh reached out to Philip “Stan” George, then superintendent at Dodge City (Kan.) Country Club, requesting a summer job.

“That summer job changed my outlook on a lot of things,” Unruh says, “especially my commitment to apply myself to my studies so that I didn’t have to rake pine needles out from under trees for the rest of my life.”

Unruh’s interest in turfgrass management grew, and he was awarded a scholarship from the Heart of America GCSA, which he used to attend his first scientific conference — for the Crop Science Society of America in Anaheim, Calif.

“It was there that I was exposed to the science behind turfgrass management, and I got to meet the authors of the textbooks that I studied from,” he says.

Unruh earned bachelor’s (1989) and master’s (1991) degrees from Kansas State University; his master’s was under the guidance of Roch Gaussoin, Ph.D. He earned his doctorate from Iowa State University in 1995 under the direction of Nick

Christians, Ph.D., and within weeks of finishing his doctorate, Unruh started his position at the University of Florida.

Unruh outlines the benefits of the USGA-spec putting green at the center, which is the site of various research projects. Photos by Darrell J. Pehr

Nurturing turfgrass managers

Unruh became the state turf Extension specialist, focused primarily on the golf and sod production industries. The position requires extensive travel supporting county Extension faculty and working with the leaders of Florida’s turf industry. He

is responsible for planning and implementing turfgrass educational field days, seminars and regional conferences for Florida and the upper Gulf Coast region.

Unruh’s work focuses on providing real-world solutions for turfgrass managers. His work centers on water quality (nutrient leaching and runoff) and quantity (drought) concerns, pest management, and new turfgrass cultivar development. He leads a

team of scientists and graduate students and works in collaboration with colleagues from the public and private sector. Unruh has authored dozens of Extension publications and trade journal articles for turf managers.

One of those graduate students is Mark Kann, now director of operations for Sod Solutions in Micanopy, Fla. Kann, a 23-year GCSAA member, got to know Unruh primarily through their work together as the BMP certification process was moving under the umbrella

of the University of Florida.

Kann was president of the Florida GCSA when UF began to oversee the BMP certification process that had been started by FGCSA. Unruh had been a key player in the industry-leading development of a BMP manual and certification process in Florida, and bringing

it under the wing of Unruh and the university made a lot of sense.

It was also a chance for Kann to pursue his goal of attaining his master’s degree under Unruh’s direction. Kann completed a study looking at the adoption of BMPs by Florida golf course superintendents as his master’s thesis.

His friendship with Unruh has continued through the years.

Kann describes Unruh as very ambitious.

“He’s passionate about everything he does,” Kann says. “I don’t know how he accomplishes everything he does in a day. He’s always got a full slate, and he’s able to keep up with it somehow.”

Kann underlines Unruh’s reputation among the Florida golf course community.

“He’s pretty well embedded in the Florida golf course industry,” Kann says. “He’s well known, well recognized and well respected by so many people in the industry, and his passion for the BMPs … he’s been there

for the whole process.”

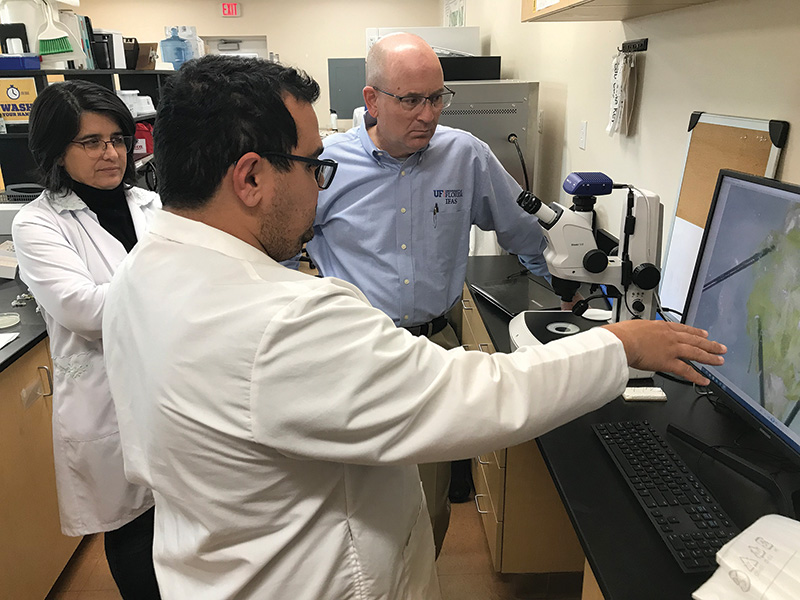

Unruh visits with Abraão Almeida dos Santos, Ph.D., visiting scholar from Brazil, and Silvana Paula-Moraes, Ph.D., assistant professor of entomology at the UF/IFAS West Florida Research and Education Center, who demonstrate the capabilities of a 3D imaging system used to generate high-resolution images of fall armyworm body parts for artificial intelligence machine-learning applications.

Longtime Florida superintendent Tim Hiers, CGCS, has known and consulted with Unruh for decades.

“I’ve been impressed with his availability when you need help,” says Hiers, director of golf course operations at the White Oak Conservation Center in Yulee, Fla., near the Florida-Georgia border. “He’s passionate about what

he does. That shows in his work, it shows in his attitude, it shows in his availability and it shows in his persistence.”

Hiers, a 44-year GCSAA member, also has been recognized for his environmental efforts. He was presented the USGA’s 2018 Green Section Award in recognition of his visionary leadership in sustainable golf course management. Hiers’ efforts helped

Collier’s Reserve Country Club in Naples, Fla., become the first Audubon International Signature Sanctuary. He also helped The Old Collier Golf Club, also in Naples, become the first course designated as an Audubon International Gold Signature

Sanctuary.

One area that has particularly impressed Hiers is the work Unruh has done in the BMP process.

“For him to kind of take the bull by the horns on the BMPs and make them a national model,” Hiers says, “that’s not only a huge undertaking, but a significant, positive impact for the golf industry in general and for the environment

in general.”

Hiers praised how the BMP process takes a practical, proactive approach to challenges.

“BMPs, if done right … you have a healthier golf course using less resources, and of course that’s a win-win,” Hiers said.

Unruh saw the need for guidance regarding environmental challenges early in his career.

“With its abundance of golf courses intertwined into sensitive ecosystems, Florida was in need of comprehensive best management practices, and I was fortunate enough to be part of the group that developed them,” he says. “Science evolves,

which means best management practices evolve as well. It’s a never-ending process, and I’m fortunate to be a contributor to the process — not only in Florida, but also across the United States of America.”

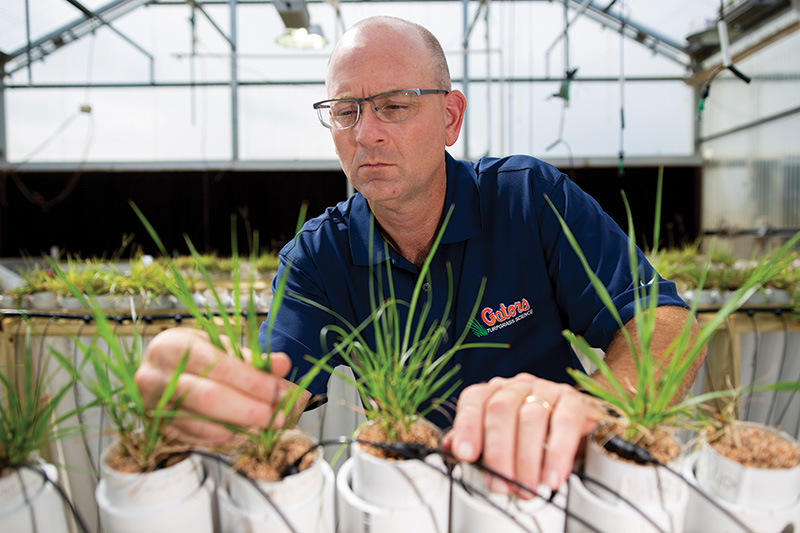

Unruh examines turf growing in the center’s greenhouse. He leads a team of scientists and graduate students and has authored over 40 Extension publications for turf managers. Photos by Tyler Jones, University of Florida/Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences

Teaching and advocacy

Unruh’s responsibilities as a faculty member range from teaching and research to Extension. Results from his team’s work are included in all three Florida turf industry BMP manuals. Unruh also serves as the primary educator for the GCSAA BMP

initiative, and he is working on the GCSAA Golf Course Environmental Profile survey series.

Unruh and GCSAA’s Ralph Dain co-teach the BMP certification in Florida. Dain, a former golf course superintendent and GCSAA’s Florida field staff representative since 2008, said he has the utmost respect for Unruh.

“What he brings to the profession is boundless,” Dain said. “I was so thrilled to see that he was going to receive that award. He’s just put in countless hours for us at GCSAA and the superintendents here in Florida. He’s

always willing to help.”

Unruh also has served as an advocate on behalf of the golf industry, with a primary focus on BMPs for golf. He meets with state representatives and the governor’s office to help educate about turfgrass management. He also serves on GCSAA’s

Research Committee and contributes to GCSAA’s national advocacy efforts, including meeting with staff and the administrator for the EPA to advocate for the BMPs.

The West Florida Research and Education Center’s Jay Research Facility celebrated its 75th anniversary in 2022.

Looking down the road

As Unruh reflects on the study and implementation of the latest research-based knowledge about turfgrass science, he sees challenges ahead.

“Due to the busyness of the golf course superintendent, many are not attending conferences and educational meetings like they once did and are now seeking information from other sources, such as the internet or the visiting sales representative,”

Unruh says. “Interestingly, the key influencers to golf course superintendents today are not university turf specialists but are sales representatives — many of whom are too busy to keep up with the evolving science.”

Attracting students to become the next generation of superintendents and turf scientists also is a concern.

“We lack students to teach due to a whole host of reasons,” he says. “Turfgrass management academic programs went through an era of tremendous growth, and the industry absorbed many of these graduates by creating second assistants, spray

techs, IPM specialists, etc. Unfortunately, some graduates couldn’t climb the ranks quickly enough and have since left the business. Today, too few students exist to meet the demand, and recruiting students into the field has proven to be difficult

as land-grant universities move away from being the ‘people’s university’ and community colleges have shuttered once-thriving programs due to low attendance.”

The maintenance building houses support equipment for the extensive field experiments underway at the center.

Limited research funding sources also sounds an alarm.

“The cost of conducting research has skyrocketed now that universities have passed the costs down to the scientist doing the work,” he says. “Many universities now require their faculty to pay land-use fees for the turf plots, greenhouse

fees, full tuition and stipends of graduate students, and they no longer provide operating dollars. Couple this with the relatively small grants provided by commodity organizations, and it is not surprising that turf faculty are shifting their emphasis

toward areas with greater funding opportunities. At the same time, many universities are moving away from commodity-oriented faculty, such as turf scientists, and are pursuing researchers who can bring in the million-dollar grants from the National

Science Foundation and National Institutes of Health. Couple these issues, and the future of turf research will be a growing challenge.”

Unruh examines a moth species being studied at the center. Photos by Darrell J. Pehr

An inspiring community

Through it all, Unruh has been inspired by many people along the way.

“Personally — hands down, my wife, Barbara,” Unruh says. “Without a doubt, she is the most giving and kind person I know. Without her by my side for the past four decades, my picture would be next to the word Scrooge in the dictionary.”

Bryan and Barbara have two adult children (both married), a 10-year-old son, two granddaughters and two grandsons ranging from 7 years to 4 months. Bryan keeps busy with construction projects, having just finished their retirement home (which he says

is 10 years early), and he is now building his workshop.

Unruh credits his collegiate advisers — Gaussoin, Christians and Jeff Nus, Ph.D. — along with UF colleagues Barry Brecke, Ph.D., and Kevin Kenworthy, Ph.D., as his academic inspiration. “They have mentored and encouraged me along the

way,” he says. “Similarly, my graduate students also offer tremendous inspiration. Their drive to learn is contagious.”

Unruh said his inspiration as a professional comes from many people.

“That list is long and includes those who have been (or were) in the golf course management business for the long game,” he says. “It includes the late Philip ‘Stan’ George, Mark Jarrell, Kevin Downing, Steve Pearson and

Ron Wright, who inspired me early in my career, and more contemporarily Tim Hiers, Matt Taylor, Darren Davis and Brian Aaron — just to mention a few.”

Unruh looks over turf experiments in the greenhouse at the West Florida Research and Education Center. “He’s passionate about everything he does,” says Mark Kann, a former graduate student of Unruh’s. “I don’t know how he accomplishes everything he does in a day. He’s always got a full slate, and he’s able to keep up with it somehow.”

Don’t let off the gas

One of Unruh’s current projects is serving as a lead scientist guiding the Golf Course Environmental Profile survey series, with the survey on pest management practices due to be released next month. He is pleased with the feedback he has received

so far on the series’ first two surveys — focused on water and nutrients. The feedback is generally positive, with the industry having reduced water use by 29%, the use of nitrogen by 41% and phosphorus by 59% since the baselines surveys

in 2005-2006.

“Across the board, these are noteworthy, and superintendents should be applauded for their effort,” Unruh says. “However, the industry cannot let off the gas. Continual improvement as evidenced by input reduction are key to the industry’s

commitment to environmental stewardship.”

Unruh’s work for the University of Florida, GCSAA and golf course superintendents has made substantial impacts in many areas, from the BMP process to inspiring scientists and much more. As Unruh reflects on all that has been accomplished and looks

to what still can be achieved, he is already setting new goals for himself.

“The first is to remain relevant,” he says. “For me, this means I must be connected to those whom I support. I firmly believe that this cannot be accomplished effectively from within my office walls — I must be on the golf course.

In today’s academic environment, with all the demands placed upon a professor, this can be a daunting task. Second is to keep getting dirt under my fingernails. Academia turns out a lot of Ph.D.s who never get dirt under their fingernails —

meaning that they lack real-world experience. The academic system can keep one in sterile confines, leading to lost relevancy. Third is to keep at the forefront of my mind that I don’t just grow grass, I grow people. And for me to do this, I

must foster my desire to learn. I don’t just want to run the race well; I want to finish well.”

Darrell Pehr (dpehr@gcsaa.org) is GCM’s science editor.