A gracious host from Texas, a creative head greenkeeper in Switzerland, a perceptive bug hunter in Florida and a water-wise superintendent in Connecticut are the 2024 winners of the 2024 Environmental Leaders in Golf Awards by GCSAA and Golf Digest in partnership with Syngenta.

The four winners, above from left, and their awards are: Mark Claburn, Tierra Verde Golf Club, Arlington, Texas, Communications and Outreach Award; Steven Tierney, MG, Golfpark Zürichsee, Wangen, Switzerland, Healthy Land Stewardship Award; Kevin Ackerman, Florida, Innovative Conservation Award; and Jim Pavonetti, CGCS, Fairview Country Club, Greenwich, Conn., Natural Resource Conservation Award.

Perhaps Tierney summed up the ELGAs — and their winners — best when he said: “We are guardians of the natural habitats, not just the golf course. In my opinion, we should be doing everything possible to maintain, to better, the environment we live in today and be able to pass it on to the next generation, knowing we have done our best to maintain and improve our golf courses and local environments.”

The awards have recognized superintendents and golf courses around the world for their commitment to environmental stewardship since 1993. In 2018 the ELGAs were updated to recognize more superintendents in more focused areas of environmental sustainability. Instead of offering national awards based on facility type, the current version of the ELGAs is based on environmental best management practices and honor specific areas of focus.

Read on to learn more about the 2024 ELGA winners.

Communications and Outreach

Mark Claburn

Tierra Verde Golf Club

Arlington, Texas

For two decades, Mark Claburn has welcomed folks to tour Tierra Verde Golf Club, a 263-acre facility in Arlington, Texas. He has hosted high schoolers, collegians and Master Naturalists.

Put on the spot and asked how many people through the years had participated in such a tour, Claburn pauses.

“I ran some quick numbers,” says Claburn, GCSAA Class A superintendent at Tierra Verde GC and 25-year association member. “Even during COVID, we had 75, 80 people out. My biggest year, we had almost 500. In a typical year, I’ll have 200, 250 people. I’d say over the years we’ve had 5,000 people.”

Perhaps even more important than that five-grand figure is the number of participants with no previous golf experience.

“I’d guess 90% have never been on a golf course,” Claburn says. “Especially with the kids. You know, if you have 20 kids, maybe one of them was a golfer. I don’t remember ever having a group where a majority was golfers.”

Mark Claburn (center) hosts 200-250 people a year for tours of Tierra Verde Golf Club in Arlington, Texas. Photos courtesy of Mark Claburn

Tierra Verde GC was the first course in Texas and the first municipal course in the world to be certified as an Audubon International Signature Sanctuary. Many of Claburn’s outreach initiatives stemmed from that, but it’s fair to say he and his team go above and beyond.

“The biggest thing for us is getting with folks who aren’t the average golfer,” says Claburn, who was the ELGA Public Golf Course and Overall Winner in 2004. “We tell them about the golf course and green spaces and try to change the image of golf, change the way people think about golf and golf courses.”

Claburn says he hosts three to four high school field trips a year of between 20 and 30 students per trip. He coordinates with the teachers ahead of time to reinforce lessons the students have in their classrooms.

“Kids learn stuff for a test and think what they’re learning won’t come up in life again,” Claburn says. “So we spend part of the tour talking about what they’re learning and how it applies to what we do.”

Tours with environmental science teachers and students from Texas Christian University or the Master Naturalists focus on golf courses and green spaces and their importance to communities.

“A lot of times, these groups are dead set against golf,” Claburn says. “Every tour, I start out by taking them up on the 10th tee, and I go, ‘Hey, just so you understand, we don’t build many big marquee parks in Texas like Central Park in New York. We build swing set parks, a couple of acres at most. So golf courses are providing that green space, for the wildlife and the tax base.”

Economics is a big part of Claburn’s talk.

Hole No. 10 at Tierra Verde Golf Club, which was the first municipal golf course in the world to be certified as an Audubon International Signature Sanctuary. Photos courtesy of Mark Claburn

“The perception is that golf has a ton of money, but that’s not the case,” he says. “What I try to tell everybody is that there’s an economic factor in everything we do to make it sustainable. The truth is that this makes financial sense.”

Claburn doesn’t consider his many tours burdensome. On the contrary, he rather enjoys them.

“It’s a change from what we regularly do,” says Claburn, who insists on involving other staffers — his mechanic and assistant superintendent, for example — in the presentations. “And I don’t remember ever having a tour where people weren’t excited about coming on the golf course, even if the weather’s bad. It’s always a very enjoyable part of my job.”

First runner-up was Carl Thompson, CGCS, at Columbia Point Golf Course in Richland, Wash., and 32-year GCSAA member. Second runner-up was Eric Verellen, GCSAA Class A superintendent at Snoqualmie Falls Golf Course in Fall City, Wash., and 12-year association member.

Healthy Land Stewardship

Steven Tierney, MG

Golfpark Zürichsee

Wangen, Switzerland

Strict Swiss law all but prevents the use of insecticides at Golfpark Zürichsee, so when destructive leatherjackets invade, Steven Tierney, MG, has to get creative.

He breaks out the tarps. And the aromatics.

“The use of black plastic tarps on greens during leatherjacket outbreaks has been successfully tested,” says Tierney, a 33-year GCSAA member who has been at Golfpark Zürichsee the past 26 years. “It’s very labor-intensive but has worked by bringing out larvae during the night. These have to be manually cleared, but due to the fact we have no insecticides for use by law, it has helped keep damage to a minimum.”

The crew also gets spicy. Another approach has been to spray a diluted mixture of garlic and mustard powder in water.

“We’re still open on the results,” says Tierney, who was the Overall and International ELGA winner in 2012. “We cannot prove this mix actually stops pest infection or if it irritates pests and they move on.”

Steven Tierney, MG, and the crew at Golfpark Zürichsee must maintain the course while adhering to stringent local and national laws. Photos courtesy of Golfpark Zürichsee

Legally, Tierney must keep a close eye on all input usage at the course. Swiss inspectors take water samples each year from four locations on-site — and they provide just two hours of advance notice — as one method to ensure compliance.

Tierney and crew employ 18-foot buffer zones around each water feature and apply inputs judiciously.

They use disease threshold guidelines for applications on greens, tees and fairways, with zero use on roughs.

Greens get no more than three fungicide applications per year.

And here’s another novel approach to environmental stewardship: All garbage containers on the property have microchips installed. When waste is collected, a local contractor scans the chips and bills each department by weight. Recycling materials are collected at no cost. Over the past 10 years, Tierney says, that has resulted in a 30% reduction in waste, with a goal of getting “as close to zero as possible.”

Golfpark Zürichsee is located just outside Wangen, Switzerland, in the Swiss Alps.

Here’s another: Sand from bunker edges, clippings and soil are stored together in a purpose-built area. The organic mix is stirred regularly, then put through a sieve/recycling machine to create a “great” sand/soil mix, which the crew uses for filling divots and in construction.

“We have a system in place in which each golfer has a divot bag,” Tierney says, and they’re expected to use it to fill divots as they encounter them. He reports that has reduced his team’s divot duties by 70%.

First runner-up was Michael Bednar, GCSAA Class A superintendent at Palouse Ridge Golf Club in Pullman, Wash., and 18-year association member. Second runner-up was Harlyn Goldman, CGCS, for his work at Needwood Golf Course in Derwood, Md. Goldman, now at Stonewall Resort in Roanoke, W.Va., is a 31-year association member.

Innovative Conservation

Kevin Ackerman

When Kevin Ackerman, then the superintendent at Royal Wood and Country Club in Naples, Fla., first encountered a basketball-sized patch of thinning turf, he guessed he was seeing the early signs of some sort of disease, maybe bermudagrass decline or melting out.

He applied the appropriate chemical curative controls, but there was no improvement. In fact, the problem was worsening. Fast.

“It was a huge shock for me,” says Ackerman, a GCSAA Class A superintendent and 25-year association member. “When it started to get worse, I thought, ‘This is unusual.’”

In fact, the cause was more unique than unusual. Sleuthing revealed the cause to be the tuttle mealybug, which, prior to Ackerman’s discovery, had only been found twice in Florida on ultradwarf bermudagrass, and never in Ackerman’s part of the Sunshine State.

Kevin Ackerman first encountered — and performed most of his experimentation in treating — the tuttle mealybug at Royal Wood and Country Club in Naples, Fla., where he served as its superintendent for 15 years. The photo at left shows the course’s No. 17 hole after treatment for mealybug damage. Photos by Kevin Ackerman

A big part of the following three years of Ackerman’s agronomic career focused on managing the pink pests, from diagnosis to treatment.

“I think a lot of people might have mealybugs present, and it might be one of those things they misidentify,” says Ackerman, noting the tuttle mealybug is a known problem in sugar cane that made the jump to zoysiagrass in residential areas before finding a home, too, in some ultradwarf bermudagrass. “Mealybugs aren’t typically found in ultradwarf bermudagrass greens, so not a lot of people are looking for it until the normal routine processes of elimination aren’t working, and that’s when I get a phone call.”

Working with the University of Florida Entomology Department, Ackerman developed an agronomic and chemical-application plan to control the insect, which he’s concerned has the potential to become more nettlesome in the future.

“They devastated a lot of zoysia turf, especially in southwest Florida, before making the jump to bermudagrass,” Ackerman says. “I’m concerned hopping more into ultradwarf greens is becoming more common. They can be very devastating.”

Ackerman says superintendents who suspect a mealybug infestation should look for sooty mold in the mornings, using a knife tip to part the thatch and examining the crown for pink dots. He heartily recommends definitive identification by sending a plug to UF Entomology for an $8 population count and analysis of the mealybug stages, adults and crawlers.

Ackerman says mealybug damage often can be confused with disease.

Ackerman’s control methods involve cultural practices such as light verticutting in combination with a mix of chemicals, depending on the severity and timing of the infestation. Because of his research and experimentation, chemical companies now target products specifically to deal with tuttle mealybugs, and golf course managers and landscapers routinely reach out to him for advice.

“The impact of my research and experiences has been significant,” Ackerman says. “Distributors, superintendents and lawn care companies have reached out to me seeking solutions for controlling the tuttle mealybug. This journey was certainly stressful and sleepless, but emerging from it has made me stronger.

“My goal is to help others by sharing the knowledge I’ve gained so they don’t have to start from scratch in their fight against this destructive pest.”

Ackerman left Royal Wood and Country Club after 15 years to go work for FMC Corp. That company was bought out by Envu, and many of the FMC Corp. employees were let go, including Ackerman.

“At that point, I had to decide what way I wanted to go,” he says. “Manufacturing? Distribution? Agronomy? After a lot of long, hard thought, I decided I wanted to return to agronomy, maybe a director role or superintendent at a nice course, so that’s what I’m in the process of doing, looking for that next spot. I’m 47. I’ve got another 20 years ahead of me.”

First runner-up was Jorge Mendoza, GCSAA Class A superintendent at Green River Golf Club in Corona, Calif., and seven-year association member. Second runner-up was Chris Robson, GCSAA Class A superintendent at Glendoveer Golf and Tennis in Portland, Ore., and 13-year association member.

Natural Resource Conservation

Jim Pavonetti, CGCS

Fairview Country Club

Greenwich, Conn.

Fairview Country Club in Greenwich, Conn., is only about 30 minutes from New York City, but in some ways it seems much more distant than that.

Case in point: Fairview CC, which lies just across Long Island Sound by that water body’s eponymous island, is fairly remote in terms of public works and has no access to city water.

As a result, Jim Pavonetti, CGCS, Fairview CC’s superintendent the past 17 years and a 29-year GCSAA member, relies almost exclusively on rainfall-recharged holding ponds to keep the course lush.

During a bunker renovation at Fairview Country Club in Greenwich, Conn., Jim Pavonetti, CGCS, chose a more drought-tolerant turf-type tall fescue around the sand borders to reduce irrigation needs.Photos by Jim Pavonetti

“Water conservation,” Pavonetti says, “becomes part of surviving a tough summer here. That’s why a lot of our environmental efforts involve water, but here it’s straight-up survival.”

And though rainfall comes and goes, Pavonetti is anticipating a battle this season.

“This past fall, 2024, was the driest fall ever recorded,” he says. “We didn’t have any measurable rainfall for about two months, and only have about six decent weeks of supplementing normal rainfall. I’m already worried.”

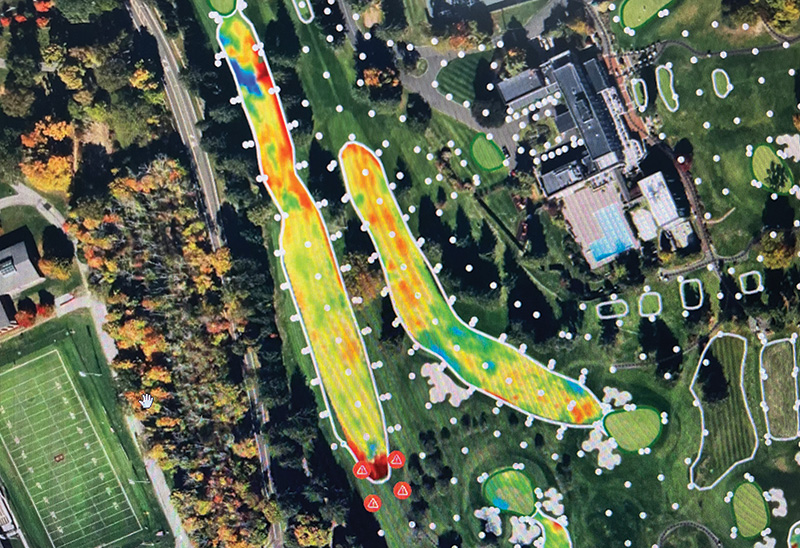

Pavonetti micromanages — in a good way — his crew’s use of the facility’s precious water resources. Using such tech as an infrared (FLIR) camera, 63 subsurface sensors, hand-held moisture meters and a turfRad microwave moisture sensor, Pavonetti’s trained crew can focus on meting out just enough water to meet playability and plant-health standards and not a drop more.

“A lot of our savings have come from micromanaging fairways the way most people manage greens,” Pavonetti says, noting the staff makes use of 450 quick-coupling valves to hand-water fairways in times of need. “We micromanage a 24-acre plot of fairways the way most high-end golf courses micromanage 3 acres of greens, saving 100,000 to 125,000 gallons of water per day.

“Labor-wise, we couldn’t do that the whole season, but we can manage it and end up saving millions of gallons of water and still have the golf course play at a really high championship quality.”

Pavonetti says without such measures, plus efforts to reduce areas that are irrigated by planting low-input turf types like fine and turf-type fall fescues and low-maintenance natives, the course would have run out of water four of the 17 seasons he has served as Fairview CC’s superintendent.

“Either we’d have burned our rough, or it would have affected membership somehow,” he says. “We might have had to restrict carts to paths only. But we’ve been able to avoid all that by taking these measures.”

Pavonetti uses sensors from turfRad to map wet and dry areas on fairways to audit the irrigation system and identify hand-watering needs.

The Natural Resource Conservation Award is Pavonetti’s second ELGA. He won the 2023 ELGA for Innovative Conservation and having been first runner-up for the 2018 and 2019 Natural Resource Conservation Award and the 2021 and 2022 Innovation Conservation Award.

“I think last year and this year are the most highly regarded ones,” says Pavonetti, who also won the 2024 Leo Feser Award. “I think since this one the overall theme is conservation all together, in my mind this is the top one.”

First runner-up was James Sua, CGCS, director of agronomy at Pei Tou Kuo Golf and Country Club in Taipei, Taiwan, and 32-year association member. Second runner-up was Justin Brimley, GCSAA Class A superintendent at Crystal Springs Golf Course in Burlingame, Calif., and 14-year association member.

Andrew Hartsock (ahartsock@gcsaa.org) is GCM’s editor-in-chief.