Turfgrass and cranberries are complementary commodities at Southers Marsh Golf Club in Plymouth, Mass. The 18-hole public course, opened in July 2001, was constructed by the Stearns family on their farm, where the cranberry bogs have been producing for more than 100 years. Photos courtesy of Will Stearns

Now that he has been a golf course superintendent/cranberry farmer for two decades, Will Stearns can answer questions about what’s on either side of the slash in his title with equal aplomb. But one question about what’s at the heart of it — specifically, which of his occupations should be listed before the slash — proves perplexing.

“That’s a good question,” says Stearns, a 20-year GCSAA member who owns and operates Southers Marsh Golf Club in Plymouth, Mass. “I guess I’d have to say I think of myself as a farmer who has a course. Can you imagine being a superintendent at a golf course that has no golfers? That’s what being a farmer is like.”

But Stearns does have golfers, and they coexist quite well with the 30 acres of cranberry bogs that don’t just adorn Southers Marsh, but are actually integral to it. Occasional adjustments are made during those couple of weeks of harvest each year, which usually begin around late September or early October.

“We don’t close the course for harvest,” Stearns says. “We might close a tee box on one hole where we’re picking that bog. You might have to play forward tees. It’s not ideal. Occasionally you’ll see somebody top one into a bog, and you watch the berries fly. But it is what it is. It’s a small price to pay for being able to do both.”

And while golf pays more bills than berries do now, there’s a reason Stearns considers himself a farmer first — because he was. His grandfather and father were cranberry farmers, “And when I got out of school,” Stearns says, “I was excited to jump into the family business.”

That excitement, however, was short-lived. In the late 1990s, Stearns recalls, the price per barrel for cranberries tanked, plummeting from nearly $60 to $18 per barrel in the span of three growing seasons. But a bit of prescience by Stearns’ father — Will Stearns III, who died this past spring — proved valuable soon enough.

“In 1995, my father was planting a 2-acre bog,” the younger Stearns says. “Not having played golf before, he thought, ‘If I have to plant grass around the bog, I might as well put in a couple of golf holes.’”

The resulting five-hole “golf course” the Stearns family carved into their farm hardly resembled the 18-hole executive layout of today. But darned if it wasn’t a blast to play.

“I remember he (the elder Stearns) took a stick and drew a circle on the ground. ‘This will be the green,’” Stearns says. “He went to the library and got a book on turf management to find out what kind of seed we needed. He planted bentgrass. We had a five-hole golf course in the backyard from ’95 until whenever we had to build the real golf course. All the greens were 1,000 square feet. That’s what we saw on TV. On TV, they always hit it next to the pin. We never played much golf, so we didn’t know those were too small. But it was fun, hitting over the bogs.

“When the cranberry market fell apart, we thought, ‘This golf thing is really fun. We have all this land around the bog ...’ If I knew then what I know now, I’m not sure I would have done it. Now we’re over the hump. I can’t believe it’s been 20 years.”

‘They had a dream’

The five-hole experiment taught the Stearnses just how little they knew about golf in general and golf courses in particular, and they needed help. They reached out to, among others, Dahn Tibbett, a former Certified Golf Course Superintendent who is the founder and president of DHT Golf Services in Plymouth.

“Dahn was great,” Stearns says. “He and my father and I sat in the kitchen and told him our plan. He said, ‘What I’m hearing is, you don’t have any money and you don’t have any experience, and you want to build a golf course. Yup. Sounds like fun. I’m in.’ Thank God we got him. He was awesome. I’m not sure everybody would have had the same optimistic attitude.”

Will Stearns IV (left), superintendent at Southers Marsh Golf Club and a 20-year GCSAA member, with his father, the late Will Stearns III, in 2014.

Asked whether, given his tenure as a golf course superintendent, he ever considered trying to talk the Stearnses out of their plan, Tibbett laughs.

“They had a dream,” he recalls, “and I helped them make it happen.”

Tibbett is credited as co-designer, along with Nick Filla. The latter did all the routing, Tibbett says, and Tibbett designed it “from the seat of the bulldozer” — a technique he learned from mentor Manny Francis, part of a long line of respected New England designer/superintendents.

Though Tibbett has been involved in countless golf course builds and renovations, Southers Marsh is the only design credit on his résumé.

“I wanted to do the project,” Tibbett says. “And I wanted to have the ability to walk away from it. It was all about the challenge of getting it done. Architects were getting way more money than I could charge. I didn’t have those credentials. I did it at a rate that was comfortable for me and comfortable for them. I trusted them, and they trusted me. It’s hard to get that kind of trust today.”

Tibbett let the land’s defining features — the cranberry bogs — dictate the design.

“You’ve got the bogs. You don’t need to put anything else in the way,” he says. “With the bogs, you’ve got enough to worry about. With a bog on the side and in front, just give ’em a landing area. We went through each hole that way, thinking, ‘Hopefully, somebody will play this course.’ I was happy we were able to do what we did.”

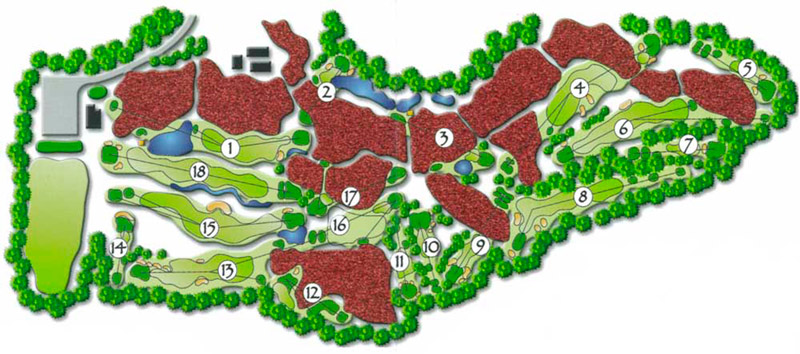

Take an aerial tour of Southers Marsh Golf Club, where crimson bogs and green turf are a feast for the eyes:

As proud as he was when the course opened for play in July 2001, Tibbett didn’t brag about his contributions. As a Plymouth local, he did, however, keep his ears tuned to his neighbors’ chatter.

“All the feedback I got, all the people there, whenever I was sitting next to them in a bar or restaurant, it was always good,” Tibbett says. “They seemed to like the contours of the greens. I never did tell them what I did out there.”

Off to turf school

The farmer in Stearns was particularly fond of the 2000 grow-in at Southers Marsh.

“Doing a grow-in is great,” he says. “There are no golfers with helpful suggestions about spraying greens and tees. You don’t have to worry about moving pins. It’s more like farming than managing a golf course.”

Speaking of which, despite his experience growing things, Stearns quickly learned during grow-in that he had some growin’ of his own to do. He enrolled in the University of Massachusetts’ Winter School for Turf Managers, a short but intense six-week certification program for aspiring turfgrass managers.

“I grew up on a farm. I know how things grow. After my first day, I was like, ‘Oh my God. I’m in over my head,’” Stearns says with a laugh. “After a while, though, you realize there are a lot of similarities. The diseases are different, and the insect pressures are different, but the lifestyle is the same.

“All the stuff I knew about cranberries, that’s what my grandfather did and told my father to do. It’s not as much a formal education. No one has a cranberry management degree in college. I was really interested to find out why they did things. They knew the right answers. But, you’re going to put fertilizer on a bog, you talk to your distributor, and he gets you fertilizer. Now ... there’s more than one type of nitrogen? That’s interesting. I absolutely loved it (UMass Winter School). It filled in so many gaps in my farming knowledge. One thing I learned when I went to turf school is, just because the guy across the way does it one way, that doesn’t mean it will work for you.”

Editor’s note: Cranberries aren’t the only food crops cultivated on golf courses. Check out several facilities’ fruit- and vegetable-growing ventures, from small garden plots to a half-acre pumpkin patch, plus find tips for getting even more growing on your course.

A different kind of golf course

Apparently, Stearns has found what works at Southers Marsh.

“We came into it without any preconceived ideas,” he says. “We probably do things differently than people who grew up caddying and playing. We came at it like, ‘This is what we do in cranberries; this is what we’ll do in turf.’ There are tons of similarities. I’m not saying there weren’t growing pains along the way, but you find things out. You look out and say, ‘Man, our bunkers look awful.’ Well, you gotta edge your bunkers. When I was in turf school, I was asking questions like, ‘How many days a week do you change your pins?’ That’s not in the book.”

Even without the bogs, Southers Marsh isn’t typical. During the dreaming stage, the two Wills debated whether to shoehorn a short 18-hole course or a full-length nine-holer onto the property, which covers about 116 acres, 45 of which are maintained turf and 30 of which are dedicated to the berry bogs.

“I was 24 at the time, and my father was maybe 50,” Stearns says. “We argued. I wanted a full-length nine holes. He wanted an executive-length 18 holes. He broke me. He said, ‘All your friends are young. They have no free time and no money. All my friends are old. They have free time and money, and they want an executive course.’

“It’s different from what people have seen. It’s shorter. There are seven par-4s, 11 par-3s. They’re all real golf course holes. You feel you’ve had a true golf experience. You’re just done quickly. It’s tougher than a lot of executive courses. There are a lot of forced carries — over the bogs. A lot of good golfers play here. The way we built it, by the seat of our pants, we were just fitting it in the natural surroundings. We weren’t moving a ton of earth. That’s not a terrible way to build a golf course. It all kind of worked out. Because of the length, we end up doing a ton of golf outings.”

Southers Marsh’s locally famous commercials playfully combine cranberries, golf and the Pilgrim history of Plymouth:

The New England GolfGuide has named Southers Marsh — a par-61 that measures 4,111 yards from the back tees — the “best golf value in Massachusetts” for 17 years running. The season usually runs mid-March through mid-December, and most years the course hosts roughly 20,000 rounds. Last year’s pandemic bump pushed that number closer to 27,000.

Fruitful labor

Now, about those bogs ...

Cranberries — “America’s original superfruit,” a registered trademark — are among the few commercially grown fruits that are native to North America. The U.S., Canada and Chile account for 98% of the world’s production of cranberries, according to the Cranberry Marketing Committee. Of the 8.7 million barrels (each barrel is 100 pounds of berries) of cranberries produced in the U.S. in 2017, Wisconsin was responsible for the largest share, with 5.4 million barrels produced there. Massachusetts was a distant second, with 1.9 million barrels, and Oregon was a similarly distant third, with 490,000.

Ocean Spray says Americans consume 20% of the country’s yearly allotment of cranberries over the week of Thanksgiving, and says roughly 200 cranberries are needed to make one can of cranberry sauce. More than 4,000 cranberries are needed to make 1 gallon of juice.

From bog to table: A picking machine at work in a bog near the course’s 11th and 12th holes. Next, the plucked cranberries will be corralled into a corner of the bog to be pumped into a truck, which will deliver them to Ocean Spray, where they’ll be made into juice or sauce.

Stearns says the family didn’t always harvest when cranberry prices were low.

“For a farm this size, golf is more profitable,” he says. “With the ups and downs of the cranberry industry, it’s gone back and forth a little bit. The price of cranberries came back in the mid-2000s and was good again for 10 years or so. Then they went in the tank worse than ever. Now they’re back a little bit. Cranberries range from a part-time job to a hobby. I really enjoy growing them. It’s like being a superintendent without golfers on your course. People ask, ‘How’s your course look?’ I don’t really know how to answer that question. But with cranberries, you measure once a year.”

At Southers Marsh, cranberries grow in 13 irregularly shaped bogs. Stearns says more than 100 years ago, the original owner poked around the property, driving long poles into the sandy soil in search of underlying peat. The topsoil gets pushed to the edges and mounded to create a berm. The berries, a perennial originally planted at Southers Marsh in 1900 with a horse and plow, grow to fruition. At harvest, each individual area is flooded. A machine knocks the berries off the vines, and the ripe fruits float to the surface. They are then encircled — “like an oil spill boom,” Stearns says — and brought to the side of the bog, then pumped into a truck.

“Then it’s off to Ocean Spray,” Stearns says of the 600,000 to 800,000 pounds of tart superfood the farm produces each season.

Then the bog is drained into the next bog, and the process repeats.

Stearns says full-time cranberry farmers would harvest in two to three weeks, but at Southers Marsh, it takes twice as long.

“We’ll go pick for two hours, then get a tournament out, then pick for two hours,” he says. “Sometimes you say, ‘We really want to pick cranberries today, but we have to mow rough.’ The harvest is really fun — for about a week. Then it’s a 24/7 thing.”

Editor’s note: See step-by-step photos of the cranberry-harvesting process on the Southers Marsh website.

‘Now we’re doing both’

Like the Southers Marsh logo that sports a crimson cranberry proudly perched upon a golf tee, berries and golfers play nicely together.

“They’re pretty much able to coexist no problem,” Stearns says. “In a normal cranberry farm, you have grass around the edges anyway. It’s not maintained like at a golf course, but it’s not a detriment, and vice versa. My father’s famous line was, ‘We’re spending so much money trying to kill grass on the cranberry bog, how difficult can it be to grow it?’ Of course, we didn’t know then the difference between poverty grass and the grass you’re growing on a green.”

Wet or dry, the cranberry bogs play like a red-stake lateral hazard.

“People always have to stay out,” Stearns says. “When it’s wet, it’s a moot point. But because it’s food, we can’t have people in the bogs. That’s fine with us. We don’t want people walking around in there.”

Southers Marsh collects all bog balls and sells them — apparently the fact that they were fished from an active cranberry bog drives up their value. Proceeds benefit the Plymouth Boys & Girls Club, which holds a benefit tournament at Southers Marsh named after Stearns’ father, Will Stearns III.

The immediate family and grandchildren of Will Stearns III, pictured in 2018.

Stearns says there are few agronomic concessions made to favor one commodity over the other.

“I don’t think anything we’re doing here is much different that any superintendent anywhere,” he says, noting that spraying season for the cranberries wraps up around mid-July. “If you’re a farmer or a superintendent, we want our products to go where they’re sprayed. It’s funny — ‘pesticide’ is such a buzzword. There’s this perception we’re just spraying willy-nilly. The stuff costs money. It takes time and effort to put it out there. It would be like us taking $100 bills and throwing them in the air.”

A contracted Ocean Spray grower, Stearns has liberally “borrowed” an idea from the parent corporation. Perhaps you’ve seen an Ocean Spray TV commercial featuring “farmers” wearing waders, standing waist-deep in a flooded bog? Southers Marsh has a similar series of its own.

“We totally ripped them off,” Stearns says with a chuckle. “The first time we were up at Ocean Spray corporate, we thought they were going to give us the cease-and-desist. I guess they do think it’s funny. So far.”

And so far, Southers Marsh is finding a way to make a go of both of its prime commodities.

“We were sort of out of cranberries for a seven-year stretch,” Stearns says. “Cranberries bounced back, and now we’re doing both, which is great. Have you ever seen a golf course that hasn’t been maintained for a few years? The same thing happens with bogs. But having a golf course around a cranberry bog is a great feature. Having a golf course around a mosquito-infested pool isn’t so great.”

Andrew Hartsock is GCM’s managing editor.