An overview of experimental plots comparing native grasses at Briarwood Country Club in Sun City, Ariz. Photos by Kai Umeda

Editor’s note: This article is reprinted with permission from the July 19, 2024, issue of the USGA Green Section Record. Copyright USGA. All rights reserved. The original article can be accessed at: https://bit.ly/3LT8shK.

Water in the Arizona desert and many other parts of the Southwest is a precious resource, and years of drought have exacerbated its limited availability for use in turfgrass and landscape settings. Golf courses are facing regulations, high water costs and other issues that are leading many to reduce managed turfgrass acreage to only greens, tees and fairways in an effort to conserve water. For example, at the Camelback Golf Club in Scottsdale, Ariz., about 65% of the acreage on its Ambiente Course has been converted from irrigated turf to a naturalized landscape that saves 40 to 50 million gallons of water per year (4).

When rough and other turfgrass is removed from the periphery of a course, the land must still be maintained aesthetically and retain a degree of functionality. One substitute for turf can be native plant materials that require less maintenance inputs and have low water use requirements. To investigate turfgrass alternatives, the University of Arizona Cooperative Extension program evaluated and compared the establishment and performance of several native grass species and ground covers for potential installation where turfgrasses are removed on golf courses.

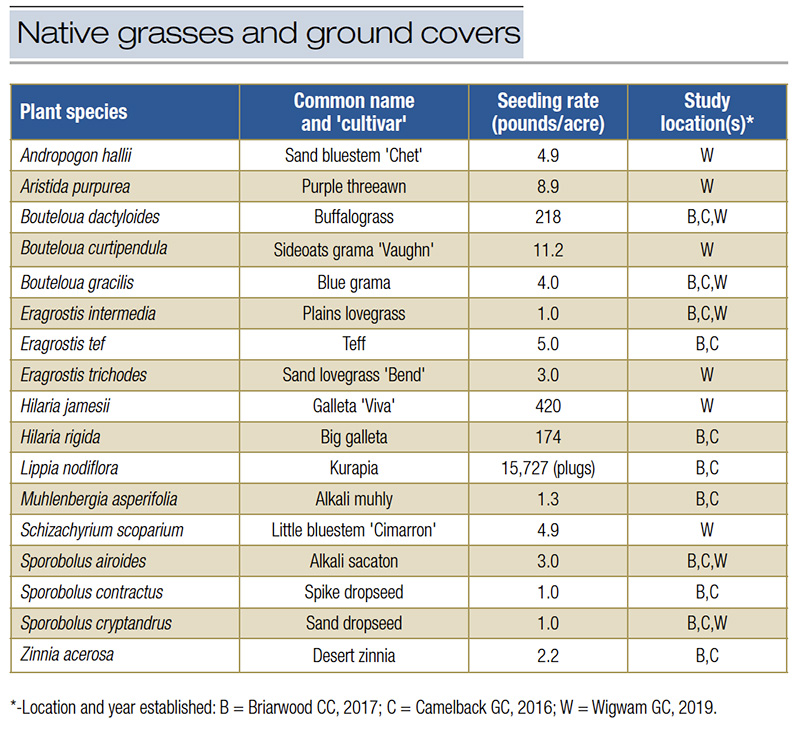

Table 1. These 17 native grasses and plant species were evaluated as low-water-use turfgrass alternatives at three Arizona golf courses where turfgrass was removed. The USDA, University of Arizona and commercial vendors provided seeds and plant materials for the study.

Plant selection and establishment

Three field experiments were conducted with 17 plant species, including 14 native grasses, an introduced annual forage grass, a native forb and an introduced landscape ground cover known as Kurapia (Table 1). The small plot replicated experiments were established on three Arizona golf courses: Camelback Golf Club in May 2016, Briarwood Country Club in Sun City West in June 2017 and Wigwam Golf Club in Litchfield Park in June 2019.

Supplemental overhead irrigation (between 0.05 and 0.25 inch/0.13 and 0.64 centimeter) was required daily to germinate and establish the seeded native grasses and Kurapia transplants at the three sites. At Wigwam Golf Club, an additional fourth replicate was planted in August to coincide with monsoon rains, and better germination and emergence was observed with this timing. Once established, the intention was to eliminate supplemental irrigation and depend on seasonal rains to sustain the plants in subsequent years.

The ground at each site was tilled by various means to prepare a surface that would enable seed germination and stand establishment. A starter fertilizer was applied only once for each of the plantings at the time of seeding or soon after stand emergence. The experimental area at Camelback was mowed in late spring and then again in the fall after the grasses matured. At Briarwood and Wigwam, the native grasses were mowed once per year during the fall or winter season.

There were significant differences in the seedling emergence and survival rate among native grasses and ground covers when averaged across each site (2). Eragrostis tef (teff), an annual forage grain crop, demonstrated the fastest rate of germination and stand establishment among the grasses. E. intermedia (plains lovegrass), Bouteloua gracilis (blue grama), Hilaria rigida (big galleta), Sporobolus cryptandrus (sand dropseed), S. airoides (alkali sacaton) and S. contractus (spike dropseed) demonstrated acceptable emergence, establishment and survival. Bouteloua dactyloides (buffalograss) failed to emerge at Briarwood and was slow to establish at Camelback, and Zinnia acerosa (desert zinnia) did not emerge at either location or in a separate laboratory germination test.

Plains lovegrass and sand dropseed grew 26 to 30 inches in height (66 to 76 centimeters) — the tallest among grasses at Briarwood and Camelback. Buffalograss and alkali muhly were the shortest grasses at under 12 inches (30.5 centimeters) in height. Blue grama, big galleta, alkali sacaton, teff and spike dropseed grew to a moderate height of 20-24 inches (51-61 centimeters).

At Wigwam, Andropogon hallii (sand bluestem Chet), Schizachyritm scoparium (little bluestem Cimarron) and Aristida purpurea (purple threeawn) rapidly emerged following a later planting during the monsoon rains in the late summer. Purple threeawn aggressively spread by seed dispersal beyond the small, planted plots. Buffalograss, the dropseeds, galleta and alkali sacaton emerged and established stands well.

Kurapia (bottom right) performed well in an experiment comparing various native grasses and ground covers conducted at Camelback Golf Club in Scottsdale, Ariz., in 2016.

Kurapia

Kurapia is a sterile cultivated variety of Lippia nodiflora that was introduced from Japan to the United States. It is a versatile noninvasive, low-growing groundcover with a dense canopy and a deep root system that increases drought tolerance, prevents soil erosion and suppresses weeds. A lengthy flowering season and attraction of honeybees and other pollinators lends it multiuse significance.

In the establishment and performance trials, Kurapia successfully established from transplanted plugs in an acceptable amount of time in 2016 and 2017 at all three sites. Kurapia mature plant height was prostrate at under 6 inches (15 centimeters) tall.

Another experiment at Wigwam compared the water use requirements of two different types of Kurapia. White- and pink-flowered varieties of Kurapia were transplanted from a single 4-quart (3.8-liter) pot into plots measuring 97 square feet (9 square meters) in May 2019. Both varieties were established and sustained during the first year with preexisting overhead irrigation. In the second year, each variety was watered at three levels of drip irrigation: a high (80%), medium (40%) and low (20%) percentage of the water typically applied to bermudagrass. The most common motivation for implementing turfgrass reduction programs in arid regions is to reduce water use. Therefore, comparing water use of alternative plants to the grass they replace is important.

Three months after planting, the white-flowered variety covered 98% of the plot area and measured about 2.0 inches (5 centimeters) in height, while the pink variety covered 72% of the plot area and measured about 3.5 inches (9 centimeters) in height. During the second year, the quality of Kurapia significantly declined when irrigated at 20% compared to the 40% and 80% levels. There was no significant difference in Kurapia quality between the 40% and 80% levels of irrigation. Once established, Kurapia could be irrigated with 40% of the water typically applied to bermudagrass when using surface drip irrigation under low desert Arizona conditions (3). Kurapia remained green throughout the year with low rates of water, maintained desired aesthetic qualities during winter and eliminated the cost of overseeding bermudagrass with ryegrass, a common practice in Arizona.

Camelback Golf Club in Scottsdale, Ariz., converted about two-thirds of the acreage on its Ambiente Course from irrigated turf to a naturalized landscape, saving 40 to 50 million gallons of water per year.

Assessing visual and overall quality of mature stands

Winter color

One of the most-desirable aesthetic characteristics of plant materials is to maintain “greenness” all year round. This is especially important on golf courses in the Southwest, since the majority of rounds played are centered around the winter months. Most native grasses become dormant and turn brown in the winter season when temperatures fall and frost occurs. Desert grasses can also go dormant with the onset of intense heat in May and June. In this study, under mild winter conditions when hard freezes did not occur, plains lovegrass, alkali sacaton and Kurapia retained acceptable green color throughout the winter. Muhlenbergia asperifolia (alkali muhly) and blue grama also maintained some green color during the winter. The dropseeds and big galleta did not retain their green winter color (1).

Growth habit

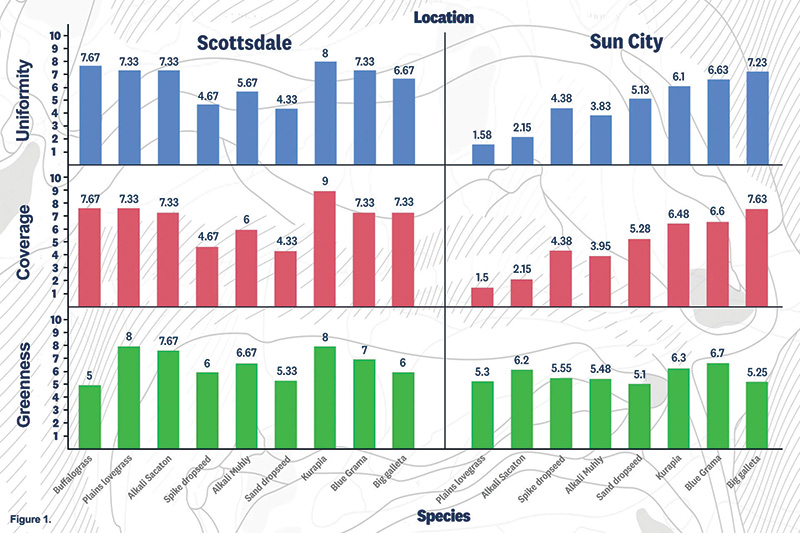

The species in our study exhibited growth characteristics and habits that ranged from low-growing Kurapia and buffalograss to intermediate-height grasses such as alkali muhly, blue grama and big galleta, to taller species, such as alkali sacaton, plains lovegrass and dropseeds. The differences in mature plant height and stand density among various native grasses and Kurapia in the field study provide golf course superintendents with valuable information when selecting plants for potential turf-reduction sites. Spatially, the taller bunch-forming grasses, such as dropseeds, alkali sacaton and plains lovegrass, provide a different aesthetic because they grow in compact tufts with more exposed bare ground compared to shorter stoloniferous species. The shorter-statured plants with more of a spreading habit, like buffalograss, alkali muhly, big galleta and Kurapia, offer more complete ground surface coverage. Additionally, plants such as buffalograss and Kurapia can be maintained as lawn or golf course rough where there are low amounts of traffic (Figure 1).

Maintenance and input requirements

In our studies, native grasses such as alkali muhly, blue grama, buffalograss and big galleta did not require frequent mowing and maintenance. They can be used in the landscape as perennial plants for erosion control and aesthetic value. These grasses are adaptable to the desert environment and can be grown under low-input conditions. Once established, they should only require minimal inputs of fertilizer, irrigation, pesticides and mowing labor.

Biodiversity increased in native grass areas

In addition to the aesthetic and water savings benefits listed above, an element that was observed in the native grasses at Camelback Golf Club during the second season was a notable increase in arthropod diversity. Pitfall traps were installed in each plot of grass species or Kurapia, and the assortment of insects included six species of ants, 13 species of bees and wasps, seven species of beetles, five species of flies and midges, four species of moths, and four species of hoppers and predators. Vertebrates like frogs and geckos were also found to inhabit these native grass areas.

Impact of turfgrass alternatives on golf

One concern among golf courses considering a turf reduction program that includes replacement with alternative ground cover is how the change will affect play. Pace of play is a critical driver of revenue and golfer satisfaction, so lost golf balls in deep grasses is not desirable. Kurapia has a prostrate growth habit that provides dense, uniform and complete surface coverage while still allowing golf balls to be found easily and played. Buffalograss, gramas, galletas and alkali muhly tended to provide full surface coverage and depth where golf balls could be difficult to find. The alkali sacaton, purple threeawn, dropseeds and bluestems grew as bunch grasses, and spacing between plants provided visible bare ground where golf balls could be found.

Initial seeding rates were used to ensure successful stand establishment of the grasses. During subsequent years of growth, thick and dense stands began to thin among the bunch grasses. Shorter-stature bunch grasses would be a better fit adjacent to play areas, while gradually taller grasses could be used in areas where golf balls are less likely to land. However, sustaining long-term succession of native grasses and wildflowers to continuously provide a natural appearance will require monitoring and labor. Perennial shrubs and volunteer desert trees may also encroach upon the sites and could require timely maintenance or removal if they interfere with play, aesthetics or functionality.

Figure 1. Evaluation of native grasses and groundcovers for greenness, surface coverage, and uniformity averaged over four seasons (summer, fall, winter and spring) in Scottsdale and Sun City West, Arizona. Values greater than 5 indicate acceptable quality for each parameter.

In summary, there are many feasible options among native grasses if courses in the Southwest are interested in replacing irrigated turf with low-water-use plant materials. Wildflowers can be integrated with the native grasses, as can native desert-adapted shrubs and trees. Incorporating less-dense, bunch-type native grasses can offer a more golfer-friendly transition between maintained turfgrass and naturalized areas or peripheral land uses. Using native grasses to replace irrigated turf can benefit biodiversity and reduce water, fertilizers, pesticides and labor costs.

As observed in these studies, once established, some perennial native grasses and Kurapia can offer year-round greenness during frost-free winters. Tall- and short-statured plants can provide enough surface cover to alleviate soil erosion due to runoff or strong winds. Environmentally friendly and aesthetically pleasing native grasses and Kurapia can significantly and successfully contribute to desert landscapes. Water inputs will be reduced to only supplemental applications when severe droughts occur, and labor can be directed away from areas that receive little play and focused on turf management on the primary playing surfaces.

The research says

- This study found that replacing managed turfgrass with native grasses and ground covers can significantly reduce water use and increase maintenance efficiency on desert golf courses.

- Stand density and height varied significantly among the native grasses and

ground covers in this study. Courses may want to use lower-growing or bunch-type options in areas adjacent to maintained turf for better playability.

- Teff demonstrated the fastest rate of germination and stand establishment among all grasses while alkali sacaton, plains lovegrass and two varieties of dropseed were the tallest. Plains lovegrass, alkali sacaton and Kurapia retained acceptablegreen color throughout frost-free winters.

- Kurapia is a low-growing, dense ground cover that demonstrated good winter color and maintained acceptable quality using 60% less water than bermudagrass.

Acknowledgements

These projects were financially supported in part by the United States Golf Association and the United States Department of Agriculture. The USDA National Institute of Food and Agriculture Project Puente provided student interns who contributed significantly to this research. The authors thank Kurapia Inc. for providing Kurapia plugs and the USDA Plant Materials Center for the grass seed. We also appreciated the cooperation of the golf course superintendents and their staffs at Camelback Golf Club, Briarwood Country Club and Wigwam Golf Club.

Literature cited

- Burayu, W., and K. Umeda. 2019. Alternative plant materials for landscapes of the Southwest USA [Abstract]. ASA, CSSA and SSSA International Annual Meetings (2019), San Antonio, Texas (https://scisoc.confex.com/scisoc/2019am/meetingapp.cgi/Paper/118270).

- Burayu, W., and K. Umeda. 2021a. Versatile native grasses and a turf-alternative groundcover for the arid Southwest United States. Journal of Environmental Horticulture 39(4):160-167 (https://doi.org/10.24266/0738-2898-39.4.160).

- Burayu, W., and K. Umeda. 2021b. Performance of two varieties of Kurapia under drip irrigation [Abstract]. 2021 ASA, CSSA and SSSA International Annual Meetings, Salt Lake City (https://scisoc.confex.com/scisoc/2021am/meetingapp.cgi/Paper/132815).

- Whitlark, B., K. Umeda, B.R. Leinauer and M. Serena. 2023. Considerations with water for turfgrass in arid environments. In: M. Fidanza, ed. Achieving sustainable turfgrass management.

Kai Umeda is an Extension agent emeritus and Worku Burayu, Ph.D., is a research specialist, both at the University of Arizona, Tucson.