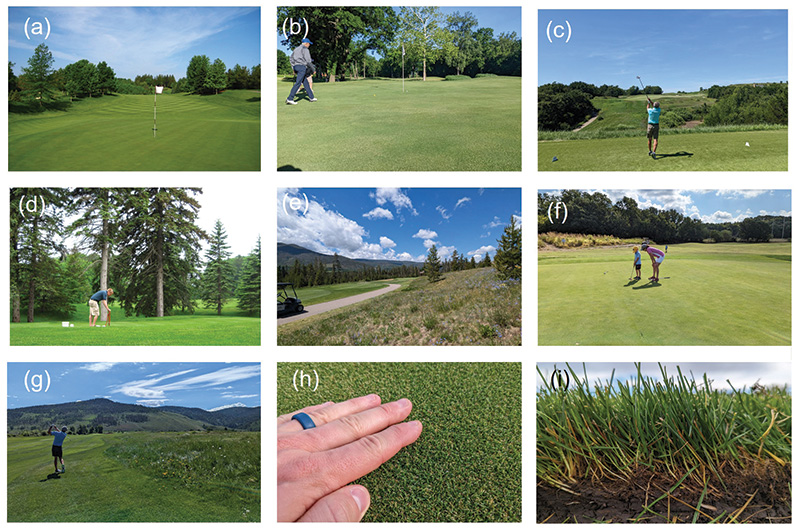

Turfgrass systems we manage on golf courses throughout the United States and worldwide not only offer a recreation space for outdoor entertainment, exercise and relaxation, but also these plant systems offer numerous ecosystem services for environmental protection and other human benefits. Photo courtesy of Ross Braun

The benefits of vegetation systems are called ecosystem services, and the associated negative aspects are called disservices. Since 1994, much research has been conducted to further understand and realize additional ecosystem services and disservices of turfgrass systems. Learning about these ecosystem services will help you better communicate and advocate for turfgrass systems.

We know golf courses provide beneficial employment opportunities for a wide range of ages and skill levels and generate economic growth. Additionally, these turfgrass systems we manage on golf courses throughout the United States and worldwide not only offer a recreation space for outdoor entertainment, exercise and relaxation, but also these plant systems offer numerous ecosystem services for environmental protection and other human benefits. What are ecosystem services? Ecosystem services (e.g., beneficial ecosystem functions or ecosystem processes) are defined by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (32) as the goods and services that produce many life-sustaining benefits we receive from nature, such as clean air and water, fertile soil for crop production, pollination and flood control. The EPA (32) states, “These ecosystem services are important to environmental and human health and well-being, yet they are limited and often taken for granted.” Taking these ecosystem services “for granted” or overlooking them is, unfortunately, a common occurrence with golf courses and public perception by non-golfers who are not educated on these benefits. Except for food products for human consumption, turfgrass systems provide many of the same or more ecosystem services (i.e., benefits) as other vegetation systems, which we will briefly discuss in this article (Figure 1).

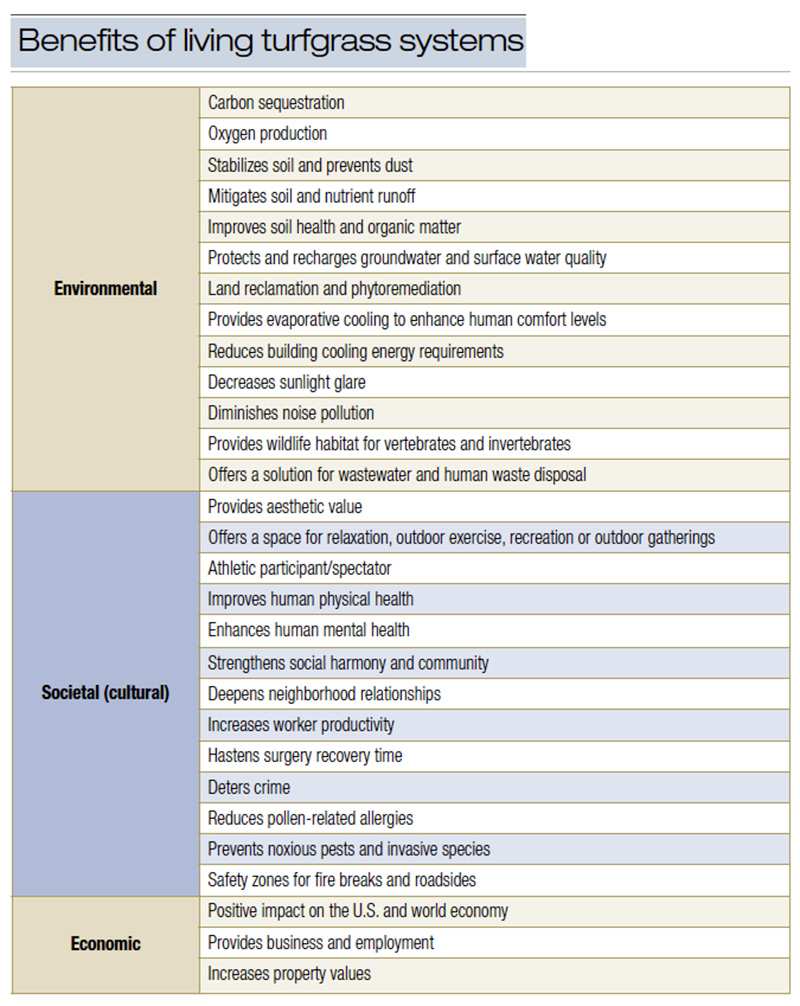

Ecosystem services of plant systems are not anything new, and the turfgrass industry and many other vegetation sectors understand that there is a need to better educate the public about the benefits of plant systems and ways we can decrease any negatives (disservices) due to management practices. Ecosystem disservices negatively impact human well-being, the environment, the economy and cultural sectors. Beard and Green (3) published one of the first comprehensive reviews and analyses of the benefits (ecosystem services) and contemporary issues (disservices) in turfgrass systems. Since 1994, Monteiro (25) and Stier et al. (31) and others have examined the human benefits turfgrass provides, as well as the associated adverse issues. Stier et al. (31) gave an update on turfgrass benefits and highlighted present concerns, such as water consumption, pollution sources of pesticides and mower emissions, and land use challenges within the turfgrass industry in the United States. Monteiro (25) used a thorough online search process to conduct a peer review of research papers published from January 1995 to March 2016 [i.e., after Beard and Green’s 1994 article (3)] to provide a European perspective. While Beard and Green’s (3) review addressed the concepts of “ecosystem services” and “ecosystem disservices,” it was absent from the terminology we now use today. The benefits and issues Beard and Green (3) identified served as a strong foundation for further discussion and analysis of turfgrass systems’ current ecosystem services and disservices today. Many of these previous papers have organized the benefits of turfgrass into categories, such as: economic, environmental, cultural or societal, or similar categories but slightly different groupings. For our paper, we used a similar model as the Christians et al. (13) textbook, which classified these turfgrass benefits (ecosystem services) into three categories: 1) environmental, 2) societal (cultural) and 3) economic. While there are some naming inconsistencies with these ecosystem service categories among papers, all authors are correct, and upon further evaluation, there are instances where some ecosystem services likely fall into multiple categories [e.g., “turfgrass acts as a fire break” could fall under an environmental benefit but also a societal (cultural) benefit].

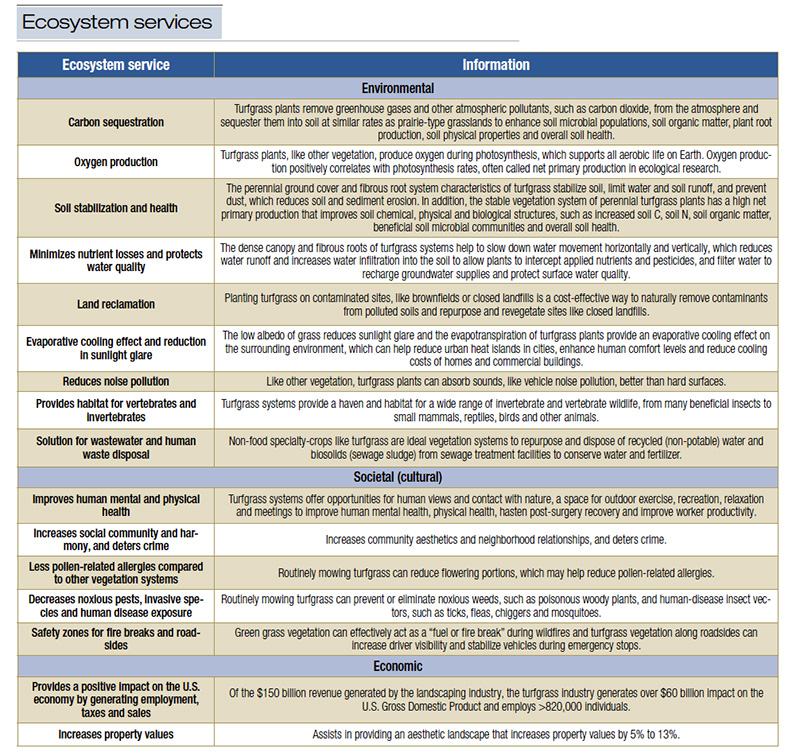

For our review paper, we followed a systematic, multistep online search process to attain and analyze this research spanning the last 30 years. Our focus was on research published between 1990 and 2024, as well as any research published before 1990 that Beard and Green (3) missed. The other approach was carefully reviewing the cited reference sections in published papers to acquire additional resources. We presented new evidence on previously mentioned ecosystem services and additional turfgrass ecosystem services not mentioned by Beard and Green (3). In addition, we identified knowledge gaps, provided an outlook toward further research needs and discussed contemporary issues (ecosystem disservices) of turfgrass systems similar to Beard and Green (3) and past authors. For this article, we do not get into the economic benefits but instead focus on the environmental and societal ecosystem services and some associated disservices (Table 1).

Figure 1. Benefits of living turfgrass systems, or ecosystem services.

Environmental benefits

Golf course turfgrass systems are managed as perennial vegetation cover compared to agronomic and horticultural food cropping systems that are annual plant systems. Why is this important? Because the benefit of continuous perennial plant vegetation for multiple consecutive years, often 20 or more years for turfgrass areas, means there is a greater positive impact these grassland systems have on improving soil quality, soil health (i.e., the soil’s ability to support agricultural production and provide other ecosystem services), soil properties and increasing soil carbon sequestration (Figure 1, Table 1). For example, through the process of photosynthesis and subsequent growth, living turfgrass plants remove greenhouse gases, such as carbon dioxide (CO2) and methane (CH4), among other atmospheric pollutants from the atmosphere and sequester (i.e., store) them into the soil at similar rates as natural prairie-type grasslands (7, 22). This process enhances beneficial soil microbial populations; soil carbon and nitrogen levels; soil organic matter; plant root production; soil chemical, physical and biological properties and structures; and overall soil health (12, 22, 23). In addition, turfgrass plants, like other vegetation, produce oxygen during photosynthesis, which supports aerobic life (i.e., oxygen-requiring life such as humans and animals) on Earth.

Proper maintenance inputs (i.e., mowing, fertilizer, water and occasional pesticides) will increase turfgrass health, cover (i.e., leaf canopy density) and the fibrous root system (Figure 2). Combining these characteristics with the perennial lifecycle creates a plant system that is highly effective at stabilizing the soil to reduce soil, water and nutrient losses (18, 24). This also limits dust and soil sediment runoff and erosion and reduces stormwater or surface water runoff because the turf canopy and roots drastically slow sediment and water movement horizontally and vertically, which allows more time for vertical infiltration into the soil to allow plants to intercept applied nutrients and pesticides, and filter water to recharge groundwater supplies and protect surface water quality from runoff or leaching (16, 24).

Turfgrass is also an excellent choice for contaminated or poor-quality soils, like brownfields and closed landfills (15). Many success stories highlight that turfgrass is a cost-effective way to remove contaminants from polluted soils naturally, repurpose and revegetate sites such as closed landfills or disturbed soils during development, and improve soil quality, health, structure and organic matter (17). For example, 70 golf courses in the United States were built on closed landfills, strip mines or industrial brownfields in 2003 (20), and many more since then (17).

Additional environmental benefits include the natural process of water transpiring and evaporating from the plant-soil system of turfgrass, which provides an evaporative cooling effect to help reduce local temperatures, especially in urban areas. Reducing local temperatures decreases urban heat island effects and building cooling costs, while enhancing human comfort levels (2). Similarly, turfgrass plants can absorb sounds from motorized equipment, vehicles and other noise pollution better than hard surfaces, improving human comfort and reducing stress (10).

Another turfgrass environmental benefit is the haven and habitat provided for a wide range of invertebrate and vertebrate wildlife in both maintained and less-maintained turfgrass areas, which is especially true for golf courses (10, 19). In 2021, the median acreage of a U.S. 18-hole golf facility was 146 acres, which includes wildlife habitats, water features and areas that require less maintenance, accounting for >20% of the total area of the golf course facility (29). This is a considerable amount of land that can be used for wildlife and plant conservation efforts (29). Across the U.S., water features, maintained turfgrass areas and natural areas combined to account for 92% of the total projected golf facility acres in 2021 (29). Turfgrass systems provide many other environmental ecosystem services, which are discussed in our paper (10).

Golf courses provide habitat for vertebrates (like the Canada geese) and invertebrates. Photos by Darrell J. Pehr

Societal benefits

Societal (cultural) benefits of turfgrass systems that positively impact our culture and human well-being are often overlooked. Being in touch with nature and viewing green spaces, like turfgrass areas found on golf courses, has been connected to better human well-being and mental health (1) (Figure 2). Moreover, turfgrass areas on golf courses provide opportunities for outdoor exercise, recreation, relaxation and socializing, leading to improved physical and mental health and increased worker productivity (4, 6) (Figure 2). These turfgrass areas also contribute to improved community aesthetics and neighborhood relationships that strengthen social community and harmony and deter crime (5, 26). Some other societal benefits of turfgrass vegetation include effective “fuel or fire breaks” during wildfires and utilization along roadsides, which increases driver visibility and stabilizes vehicles during emergency stops (10).

We believe these societal (cultural) ecosystem services are more important today than 30 years ago when Beard and Green (3) highlighted some human physical and mental health benefits. Since 1994, the American Public Health Association (1) mentioned a growing body of evidence highlighting that access to nature for people of all ages, social groups and abilities alleviates important public health problems such as obesity, stress, social isolation, injury and violence. These social benefits are increasingly important in urban areas, which have high human activity and less green space compared to suburban areas. Although digital communication methods have increased since 1994, research shows lower levels of social connectedness (e.g., reduced social interactions) and increases in mental health issues associated with digital communication (e.g., social media, online gaming, email, text messaging) (27). Therefore, golf courses and other green spaces’ sociological and psychological health benefits are likely more important today than 30 years ago to improve social harmony and community and foster real face-to-face interactions with friends, neighbors and others in our communities. We believe policymakers and city planners must consider these important turfgrass ecosystem services and strategically incorporate turfgrass areas such as parks, golf courses and other urban green spaces to enhance public health and social community and harmony.

Table 1. Information about ecosystem services of living turfgrass systems. Note: For references for each ecosystem service, please see Braun et al (10).

Disservices

While there are many beneficial ecosystem services associated with turfgrass systems, there are also negatives. These disservices are present in all vegetation systems, including turfgrass, and therefore our turfgrass management decisions need careful consideration (28). Shackleton et al. (28) mentioned that ecosystem disservices accompany all plant systems, and these disservices can be minimized if the correct approach is taken to directly reduce disservices, promote the integrity and resilience of plant systems, and thoroughly assess the tradeoff between services and disservices. Some turfgrass system disservices we address in our paper are greenhouse gas and particulate matter emissions, site-specific high-water consumption, nutrient and pesticide inputs and losses, mowing inputs, and lack of pollinator-friendly vegetation (10). We highlight these disservices and provide recent research updates on these topics and solutions.

One disservice we would like to discuss in this article is site-specific high-water consumption in some turfgrass systems. Unfortunately, a common misconception by the public is that all turfgrass areas receive supplemental irrigation; however, except for golf courses and sports fields, most turfgrass systems found at parks, cemeteries, roadsides and many home lawns do not have in-ground irrigation, nor do they receive supplemental irrigation. There are many textbooks, research articles, trade article publications and symposiums dedicated to water conservation in the turfgrass industry. This issue is clear to both turfgrass scientists and turfgrass professionals, such as golf course superintendents, who are continually incorporating strategies to reduce irrigation inputs. Both Beard and Green (3) and Stier et al. (31) highlight that while water use rates (i.e., evapotranspiration) have been extensively studied for nearly all commonly grown turfgrass species, scant research has been conducted on the water use rates of ornamental plants, especially trees and shrubs used in landscapes. This shows how important and how much energy has been directed at this topic for the last 30 years in the turfgrass industry. Regardless, turfgrass water use remains the primary target of criticism in many regions of the world. Braun et al. (8, 9) and Colmer & Barton (14) reviewed and highlighted >100 research experiments in the last 60 years related to turfgrass plant water requirements, irrigation rates and responses to drought stress in both cool-season and warm-season turfgrass species, respectively. In certain regions, an effective solution to the problem of water scarcity could be the reuse of wastewater for irrigation purposes. This recycled water, unsuitable for human consumption or food crops, can be used to grow non-food crops like turfgrass (21), and 21% of applied irrigation across U.S. golf courses was recycled water in 2020 (30). Golf course superintendents are often leading the way in the entire field of horticulture for incorporating innovative water conservation strategies. For example, likely due to their educational background and awareness, U.S. golf course superintendents have continued to reduce the amount of water applied on the golf courses by more than 25% over the last 15 years (30). Continuing to be educated on these disservices and taking proper action will help alleviate public scrutiny and criticism of turfgrass systems.

Figure 2. Examples of ecosystem services provided by living turfgrass systems on golf courses. Societal (cultural) services such as increased aesthetics and community (a, b, c, f), space for recreation, sports, exercise and relaxation to promote community, social harmony and enhance mental and physical health, (b, c, d, f, g). Environmental ecosystem services such as wildlife habitat, organic matter production, dense canopy and roots to filter nutrients and water and minimize soil erosion (e, g, h, i). All photos by Ross Braun.

Final comments

Turfgrass systems are used in various urban and suburban settings, including residential lawns; public areas, like parks and schools; sports fields; golf courses; sod and seed production farms; and roadsides. These turfgrass areas are often visible to the public, attracting unsupported scrutiny, especially by those uneducated on turfgrass systems’ ecosystem services of environmental, societal and economic benefits. Yes, turfgrass areas increase aesthetics in the landscape, but there is strong evidence of many other benefits (i.e., ecosystem services) linked to turfgrass systems. Most of these benefits positively enhance our environment, such as improving soil health and water quality, stabilizing our soil, removing carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases from the atmosphere, providing oxygen for us to breathe, providing habitat for many vertebrate and invertebrate wildlife and many other environmental benefits. In urban green spaces, turfgrass contributes to plant biodiversity, promotes ecosystem balance and improves human physical health, mental health and personal and social well-being. These are especially evident with golf courses.

It is important to remember that every vegetation system has some negative aspects, also known as disservices. However, with proper maintenance practices to promote healthy and dense turfgrass cover, turfgrass can provide numerous benefits that outweigh the negatives. Golf course superintendents must understand these ecosystem services and be able to communicate them effectively to clientele, local policymakers and city planners. Any strategies or regulations that alter the management practices of turfgrass need to be considered carefully. For example, Monteiro (25) mentioned that water conservation in turfgrass systems should consider multiple strategies instead of a single-factor decision like “shutting off the water completely” for the reason that, if irrigation is reduced too much, then the turfgrass benefits may be reduced or neutralized. Thus, regardless of the management input (i.e., fertilizer, pesticides, irrigation, mowing), hasty decision-making to eliminate or ban certain inputs to alleviate the negative aspect (disservice) is strongly discouraged because it may have a larger impact on plant growth and the accompanying beneficial ecosystem services. Therefore, reducing disservices needs to be considered in a balanced, carefully planned approach, likely through multiple strategies that still promote a healthy, dense, actively growing turfgrass that provides ecosystem services. Braun et al. (11) highlighted research-based strategies to reduce inputs and emissions in turfgrass systems.

We encourage you to read the full manuscript (10), which is open-access available in Crop Science (http://doi.org/10.1002/csc2.21383) to become familiar with the many benefits turfgrass systems provide so you can effectively communicate to employees, clientele and many others to promote turfgrass and the golf course industry.

Mowing inputs are among the disservices associated with living turfgrass systems. Photo courtesy of Ross Braun

The research says

- Turfgrass systems provide critical ecosystem services involving environmental, social (cultural) and economic benefits for humans from vegetation systems.

- Turfgrass on golf courses and other areas enhances soil health and quality, reduces stormwater runoff and filters and cleans water to help recharge groundwater supplies.

- Like other vegetation systems, turfgrass systems provide a cooling effect to help enhance human comfort levels and reduce energy use in buildings.

- Turfgrass on golf courses also increases human well-being, fostering mental and physical health, community relationships and safety.

- Turfgrass systems, like those on golf courses, are constantly scrutinized by the public; therefore, continued education and awareness of both ecosystem services and disservices of turfgrass systems will help golf course superintendents communicate and advocate for golf courses.

Literature cited

- American Public Health Association. 2013. Improving health and wellness through access to nature. Accessed Jan. 17, 2024. (https://www.apha.org/policies-and-advocacy/public-health-policy-statements/policy-database/2014/07/08/09/18/improving-health-and-wellness-through-access-to-nature).

- Aram, F., E.H. García, E. Solgi and S. Mansournia. 2019. Urban green space cooling effect in cities. Heliyon 5:1-31 eo1339 (https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2019.e01339).

- Beard, J.B., and R.L. Green. 1994. The role of turfgrasses in environmental protection and their benefits to humans. Journal of Environmental Quality 23:452-460.

- Bowler, D.E., L.M. Buyung-Ali, T.M. Knight and A.S. Pullin. 2010. A systematic review of evidence for the added benefits to health of exposure to natural environments. BMC Public Health 10:456 (https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-10-456).

- Branas, C.C., R.A. Cheney, J.M. MacDonald, V.W Tam, T.D. Jackson and T.R. Ten Have. 2011. A difference-in-differences analysis of health, safety, and greening vacant urban space. Journal of Epidemiology 174(11):1296-1306 (https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwr273).

- Bratman, G.N., C.B. Anderson, M.G. Berman, B. Cochran, et al. 2019. Nature and mental health: An ecosystem service perspective. Science Advances 5(7):eaax0903 (https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.aax0903).

- Braun, R.C., and D.J. Bremer. 2019. Carbon sequestration in zoysiagrass turf under different irrigation and fertilization management regimes. Agrosystems, Geosciences & Environment 2(1):180060 (https://doi.org/10.2134/age2018.12.0060).

- Braun, R.C., D.J. Bremer, J.S. Ebdon, J.D. Fry and A.J. Patton. 2022a. Review of cool-season turfgrass water use and requirements: I. Evapotranspiration and responses to deficit irrigation. Crop Science 62(5):1661-1684 (https://doi.org/10.1002/csc2.20791).

- Braun, R.C., D.J. Bremer, J.S. Ebdon, J.D. Fry and A.J. Patton. 2022b. Review of cool-season turfgrass water use and requirements: II. Responses to drought stress. Crop Science 62(5):1685-1701 (https://doi.org/10.1002/csc2.20790).

- Braun, R.C., P. Mandal, E. Nwachukwu and A. Stanton. 2024. The role of turfgrasses in environmental protection and their benefits to humans: 30 years later. Crop Science 64 (6):2909-2944 (http://doi.org/10.1002/csc2.21383).

- Braun, R.C., C.M. Straw, D.J. Soldat, M.A.H. Bekken, A.J. Patton, E.V. Lonsdorf and B.P. Horgan. 2023. Strategies for reducing inputs and emissions in turfgrass systems. Crop, Forage and Turfgrass Management 9(1):e20218 (https://doi.org/10.1002/cft2.20218).

- Chou, M.Y., D. Pavlou, P.J. Rice, K.A. Spokas, D.J. Soldat and P.L. Koch. 2024. Microbial diversity and soil health parameters associated with turfgrass landscapes. Applied Soil Ecology 105311 (https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsoil.2024.105311).

- Christians, N.E., A.J. Patton and Q.D. Law. 2017. Fundamentals of turfgrass management (Fifth edition). John Wiley & Sons, New York.

- Colmer, T.D., and L. Barton. 2017. A review of warm-season turfgrass evapotranspiration, responses to deficit irrigation, and drought resistance. Crop Science 57(S1):S98-S110 (https://doi.org/10.2135/cropsci2016.10.0911).

- Cook, R.L., and D. Hesterberg. 2013. Comparison of tree and grasses for rhizoremediation of petroleum hydrocarbons. International Journal of Phytoremediation 15(9):844-860 (https://doi.org/10.1080/15226514.2012.760518).

- Côtè, L., and G. Grègoire. 2021. Reducing nitrate leaching losses from turfgrass fertilization of residential lawns. Journal of Environmental Quality 50:1145-1155 (https://doi.org/10.1002/jeq2.20277).

- Deegan, J.S. 2019. Grass over garbage: Golf courses give landfill sites a second life. Golf Pass. Aug. 6 2019. Accessed March 19, 2024 (https://www.golfpass.com/travel-advisor/articles/grass-over-garbage-golf-courses-give-landfill-sites-a-second-life).

- Easton, Z.M., and A.M. Petrovic. 2004. Fertilizer source effect on ground and surface water quality in drainage from turfgrass. Journal of Environmental Quality 33(2):645-655 (https://doi.org/10.2134/jeq2004.6450).

- Gallo, T., M. Fidino, E.W. Lehrer and S.B. Magle. 2017. Mammal diversity and metacommunity dynamics in urban green spaces: Implications for urban wildlife conservation. Ecological Applications 27:2330-2341 (https://doi.org/10.1002/eap.1611).

- Gold, J. 2003. Golf courses multiplying on formerly unusable lands. The Washington Post, Dec. 6, 2023. Accessed March 18, 2024 (https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/politics/2003/12/07/golf-courses-multiplying-on-formerly-unusable-landfills/9d1e97d4-77ab-4230-9d20-605b99053b23/).

- Harivandi, M.A. 2000. Irrigating turfgrass and landscape plants with municipal recycled water. ISHS Acta Horticulturae 537: III International Symposium on Irrigation of Horticultural Crops 537:697-703 (https://doi.org/10.17660/ActaHortic.2000.537.82).

- Law, Q.D., and A.J. Patton. 2017. Biogeochemical cycling of carbon and nitrogen in cool-season turfgrass systems. Urban Forestry and Urban Greening 26:158-162 (https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ufug.2017.06.001).

- Law, Q.D., J.M. Trappe, Y. Jiang, R.F. Turco and A.J. Patton. 2017. Turfgrass selection and grass clippings management influence soil carbon and nitrogen dynamics. Agronomy Journal 109(4):1719-1725 (https://doi.org/10.2134/agronj2016.05.0307).

- Linde, D.T., T.L. Watschke, A.R. Jarrett and J.A. Borger. 1995. Surface runoff assessment from creeping bentgrass and perennial ryegrass turf. Agronomy Journal 87:176-182. (https://doi.org/10.2134/agronj1995.00021962008700020007).

- Monteiro, J.A. 2017. Ecosystem services from turfgrass landscapes. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening 26:151-157 (https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ufug.2017.04.001).

- Sadler, R.C., J. Pizarro, B. Turchan, S.P. Gasteyer and E.F. McGarrell. 2017. Exploring the spatial-temporal relationships between a community greening program and neighborhood rates of crime. Applied Geography 83:13-26 (https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apgeog.2017.03.017).

- Scott, D.A., B. Valley and B.A. Simecka. 2017. Mental health concerns in the digital age. International Journal of Mental Health Addiction 15:604-613 (https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-016-9684-0).

- Shackleton, C.M., S. Ruwanza, G.K. Sinasson Sanni, S. Bennett, P. De Lacy, R. Modipa, N. Mtatai, M. Scahikonye and G. Thondhlana. 2016. Unpacking Pandora’s box: Understanding and categorising ecosystem disservices for environmental management and human wellbeing. Ecosystems 19:587-600 (https://doi.org/10.1007/s10021-015-9952-z).

- Shaddox, T.W., J.B. Unruh, M.E. Johnson, C.D. Brown and G. Stacey. 2023. Land-use and energy practices on U.S. golf courses. HortTechnology 33(3):296-304 (https://doi.org/10.21273/HORTTECH05207-23).

- Shaddox, T.W., J.B. Unruh, M.E. Johnson, C.D. Brown and G. Stacey. 2022. Water use and management practices on U.S. Golf Courses. Crop, Forage and Turfgrass Management 8(2):e20182 (https://doi.org/10.1002/cft2.20182).

- Stier, J.C., K. Steinke, E.H. Ervin, F.R. Higginson and P.E. McMaugh. 2013. Turfgrass benefits and issues. Pages 105-145. In: J.C. Stier, B.P. Horgan and S.A. Bonos, eds. Turfgrass: Biology, use, and management. Agronomy Monograph 56. ASA, CSSA, SSSA. (https://doi.org/10.2134/agronmonogr56.c3).

- United States Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA). 2024. Ecosystem Services Research. Accessed Jan. 12, 2024. (https://www.epa.gov/eco-research/ecosystem-services-research#:~:text=Ecosystem%20goods%20and%20services%20produce,and%20often%20taken%20for%20granted).

Ross C. Braun (rossbrau@ksu.edu) is an assistant professor and the director of the Rocky Ford Turfgrass Research Center in the Department of Horticulture and Natural Resources at Kansas State University, Manhattan; Parul Mandal, Emmanuel Nwachukwu and Alex Stanton are graduate research assistants in the Department of Horticulture and Natural Resources at Kansas State University, Manhattan.