In cool, humid regions such as the Pacific Northwest, where disease-prone annual bluegrass (Poa annua) dominates, Microdochium patch is a major concern of golf course superintendents (7). Fungicides can be used to effectively manage this disease, but recent legislation restricting the use of pesticides (3) has made it difficult in certain areas to ensure quality putting surfaces throughout winter and spring. When annual bluegrass dominates turfgrass swards, alternatives to traditional fungicides are desirable.

Anecdotally, iron sulfate has been observed to mitigate Microdochium patch, but no studies have been published in scientific journals prior to this experiment (5). Early studies also have shown that winter nitrogen applications increase Microdochium patch incidence, but the rates used in those studies (1) were higher than current spoon-feeding rates (2). Therefore, we implemented a field study on an annual bluegrass putting green at Oregon State University to explore the effects of different combinations of iron sulfate and urea applications on the incidence of Microdochium patch over the course of two years.

Materials and methods

A putting green was constructed by placing 6 inches (15.24 cm) of USGA-recommended- particle-size sand directly on a naturally sloping native soil area in April 2013. Annual bluegrass was established using aerification cores from Corvallis (Ore.) Country Club.

The green was grown in using a compound fertilizer with micronutrients (Andersons 28-5-18). A total of 3.8 pounds nitrogen/1,000 square feet (18.57 grams/square meter) was applied from April to July. In August, 0.2 pound nitrogen/1,000 square feet (0.98 gram/square meter) was applied every two weeks using the same fertilizer, and in September, 0.2 pound nitrogen/1,000 square feet was applied every two weeks using urea. In between trial years, a total of 1.6 pounds nitrogen/1,000 square feet (7.82 grams/square meter) was applied using the Andersons fertilizer.

Mowing height was set at 0.15 inch (3.81 mm). Over the summer, aerification and topdressing were carried out, and fungicides were applied to control dollar spot and anthracnose. No fungicides were applied during the trial dates from September through April.

The experimental design consisted of a randomized complete block design with a 5 × 3 factorial arrangement that included five rates of iron sulfate heptahydrate (0, 0.25, 0.5, 1.0 and 2.0 pounds iron sulfate/1,000 square feet; 0, 1.22, 2.44, 4.88 and 9.76 grams/square meter) and three rates of nitrogen applied as urea (0, 0.1 and 0.2 pound nitrogen/1,000 square feet; 0, 0.49 and 0.98 gram/square meter).

Applications were made every two weeks from Sept. 26, 2013 to April 15, 2014, and repeated from Sept. 22, 2014 to April 15, 2015. All treatments were applied using a CO2-pressurized backpack sprayer with a pressure of 40 psi (280 kpa) and a carrier volume of 2 gallons water/1,000 square feet (814 liters/hectare).

To assess whether the treatments would influence wear tolerance, golfer traffic representing 76 golf rounds per day was replicated by walking on the plots with golf shoes five days a week, following the protocol of Hathaway and Nikolai (4). Response variables included percent disease, turfgrass quality and fertility analyses.

Results and discussion

Urea

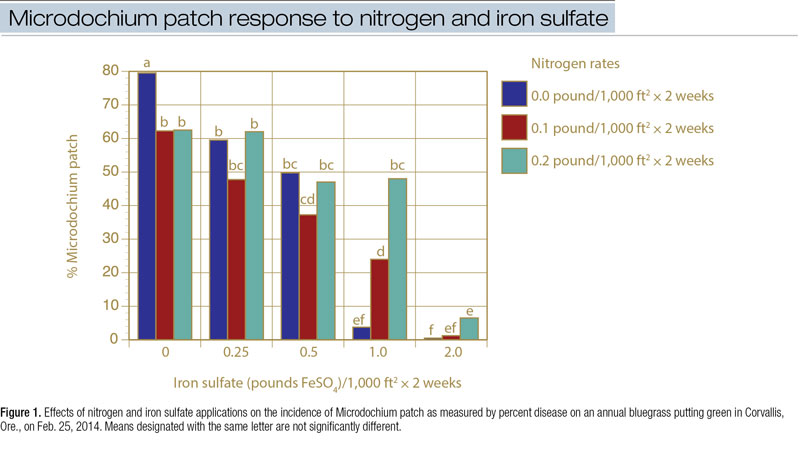

In the first year, urea applications did not increase the incidence of Microdochium patch when applied in combination with low rates of iron sulfate (Figure 1, above). Urea applications led to greater Microdochium patch incidence only when they were applied in conjunction with 1 or 2 pounds iron sulfate/1,000 square feet. The only instance in which no nitrogen led to a lower incidence of Microdochium patch compared with a rate of 0.1 pound nitrogen/1,000 square feet was at the 1 pound iron sulfate level.

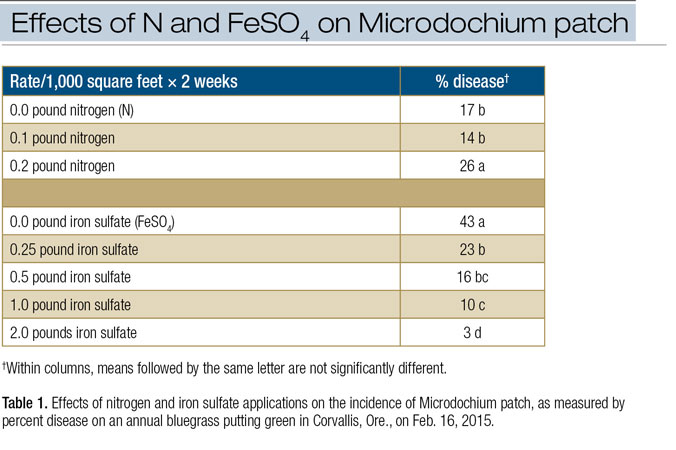

In the second year of the study, application of nitrogen at 0.1 pound/1,000 square feet did not increase Microdochium patch compared with plots not receiving any nitrogen (Table 1, above). These two years of data strongly suggest that applying 0.1 pound nitrogen/1,000 square feet every two weeks in the form of urea does not lead to a greater incidence of Microdochium patch than applying no nitrogen.

Iron sulfate

For iron sulfate applications in the first year, the lowest level of Microdochium patch was observed when 2 pounds iron sulfate/1,000 square feet was applied every two weeks in the absence of urea followed by 2 pounds of iron sulfate in combination with 0.1 pound nitrogen/1,000 square feet or 1 pound of iron sulfate in the absence of urea (Figure 1).

In year two, all iron sulfate applications (0.25, 0.5, 1.0 and 2.0 pounds/1,000 square feet) resulted in less Microdochium patch when compared with no iron sulfate applications (Table 1), with disease incidence decreasing as the rate of iron sulfate increased. This two-year study strongly suggests that iron sulfate applications reduce the incidence of Microdochium patch on annual bluegrass putting greens.

Right: Nitrogen and iron sulfate treatments were applied to an annual bluegrass putting green in Corvallis, Ore. The green was not treated with fungicides and received replicated golfer traffic. The two plots shown were treated every two weeks with 2.0 pounds of iron sulfate/1,000 square feet beginning in September 2013. The top plot also received 0.1 pound nitrogen/1,000 square feet every two weeks in the form of urea; the bottom plot did not receive any nitrogen. The intensity of Microdochium patch disease pressure surrounding the trial can be observed on the right and in the lower section of the photo, which was taken in January 2014. Photo by C. Mattox

Right: Nitrogen and iron sulfate treatments were applied to an annual bluegrass putting green in Corvallis, Ore. The green was not treated with fungicides and received replicated golfer traffic. The two plots shown were treated every two weeks with 2.0 pounds of iron sulfate/1,000 square feet beginning in September 2013. The top plot also received 0.1 pound nitrogen/1,000 square feet every two weeks in the form of urea; the bottom plot did not receive any nitrogen. The intensity of Microdochium patch disease pressure surrounding the trial can be observed on the right and in the lower section of the photo, which was taken in January 2014. Photo by C. Mattox

Even though iron sulfate applications were shown to reduce the incidence of Microdochium patch, turfgrass quality ratings were never considered acceptable for putting greens in either year of the study, because iron sulfate caused blackening and thinning of the turfgrass. Nitrogen applications tended to improve turfgrass color, but the density of the turfgrass remained unacceptable for putting greens.

Fertility analyses revealed that iron sulfate applications would likely lead to a lower soil pH and higher sulfate levels over time (5). These may be of concern to superintendents, because there is evidence that acidifying fertilizer additions may increase the risk of the incidence of anthracnose on annual bluegrass (6).

Conclusion

This study provides the first evidence to suggest urea applied at 0.1 pound/1,000 square feet every two weeks from mid-September to mid-April does not lead to an increase in the incidence of Microdochium patch. This information may be useful to superintendents who desire annual bluegrass growth in fall and winter. This is also the first replicated trial to provide evidence of effective rates for the management of Microdochium patch using iron sulfate. Although this information is useful to superintendents, the higher rates of iron sulfate used in this study led to turfgrass thinning considered unacceptable for putting greens, and also led to lower soil pH and higher sulfate soil levels that may cause other concerns over the long term.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank GCSAA, the Northwest Turfgrass Association, the Oregon GCSA, the Oregon Turfgrass Foundation, the United States Golf Association, the Western Canada Turfgrass Association and the Western IPM Center for funding this study.

Literature cited

- Brauen, S.E., R.L. Goss, C.J. Gould and S.P. Orton. 1975. The effects of sulphur in combination with nitrogen, phosphorus and potassium on colour and Fusarium patch disease on Agrostis putting green turf. Journal of the Sports Research Institute 51:83-91.

- Christians, N.E. 2007. Fundamentals of turfgrass management. 3rd edition. Wiley, Hoboken, N.J.

- Christie, M. 2010. Private property pesticide by-laws in Canada. Accessed Sept. 7, 2017.

- Hathaway, A.D., and T.A. Nikolai. 2005. A putting green traffic methodology for research applications established by in situ modeling. International Turfgrass Society Research Journal 10:69-70.

- Mattox, C.M., A.R. Kowalewski, B.W. McDonald, J.G. Lambrinos, B.L. Daviscourt and J.W. Pscheidt. 2017. Nitrogen and iron sulfate affect Microdochium patch severity and turf quality on annual bluegrass putting greens. Crop Science 57:S-293-S-300.

- Schmid, C.J., B.B. Clarke and J.A. Murphy. 2017. Anthracnose severity and annual bluegrass quality as influenced by nitrogen source. Crop Science 57:S-285-S-292.

- Vargas, J.M. 2005. Management of turfgrass diseases. 3rd edition. Hoboken, N.J.

Clint Mattox is a graduate student, Alec Kowalewski is an assistant professor, and Brian McDonald is a senior faculty research assistant in the Department of Horticulture at Oregon State University, Corvallis, Ore.