Wetting agents are often marketed as a means of making greens “fast and firm” and enhancing green speed. Here, green speed is being measured on a TifEagle bermudagrass putting green. Photo by Travis Shaddox

Wetting agents have been used to alleviate soil hydrophobicity for decades. In fact, wetting agents are so common on golf courses that there is a good chance that some part of your course is reaping the benefits of a wetting agent application as you are reading this article. The claims that wetting agents result in increased moisture distribution and alleviation of hydrophobic soils are now well documented with little room for debate. Current research on wetting agents is aimed at exploring their impacts on soil microbiology (2) and interaction with plant protectants (2, 3, 4).

Interestingly, one wetting agent marketing claim that has not been scrutinized is the notion that wetting agents produce “fast and firm” surfaces. We recall seeing this claim on a product container 10 or 15 years ago, and not much thought was given. It was assumed that the manufacturer had tested the product and discovered that the putting green was firmer and faster with the wetting agent than without it. Fast-forward 10 years, and a thorough review of the literature on wetting agents reveals little information on the actual influence of wetting agents on surface firmness and putting green speed.

In 2014, researchers investigated the influence of several wetting agents on a Minnesota putting green built to USGA recommendations. They reported that none of the wetting agents influenced surface firmness in the first year (1), and, in the second year, some wetting agents marketed as being able to increase firmness actually resulted in softer surfaces.

Other work has been conducted to determine a correlation between volumetric water content (VWC) and firmness (6). However, data regarding the influence of wetting agents on putting green speed remains elusive. Therefore, we set out to investigate the influence of wetting agents on putting green speed.

The experiment

This study was conducted simultaneously on putting greens at the University of Florida’s Research and Education Centers in Jay and in Fort Lauderdale during 2018. Both studies used 6.6- × 9.8-feet (2- × 3-meter) plots and were arranged in a randomized complete block design. Each putting green was constructed according to USGA recommendations. The putting green in Jay had been established for more than five years, and the Fort Lauderdale putting green was established in 2016.

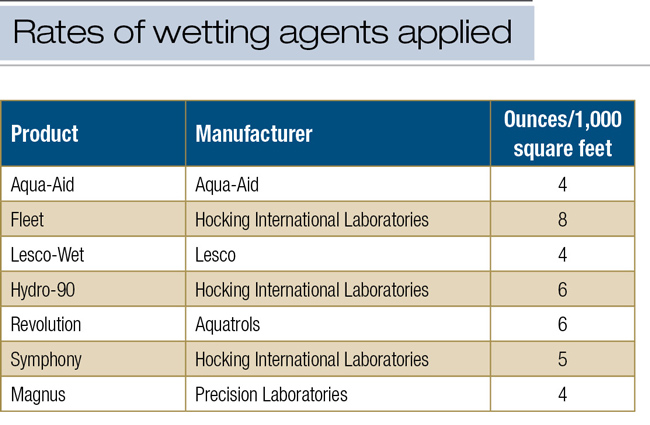

Table 1. Manufacturer and application rate of wetting agents applied to TifEagle hybrid bermudagrass in Fort Lauderdale, Fla., and Jay, Fla., in 2018.

Treatments (Table 1, above) were applied in Jay during the first week of each month from June through November. In Fort Lauderdale, treatments were applied the first week of each month from January through December. Wetting agents were applied at the highest labeled 30-day interval rate. Treatments were diluted in water and applied uniformly to each plot using a backpack sprayer. Following treatment application, irrigation delivered 0.2 inch (0.5 centimeter) of water to move the treatments into the profile.

Soil VWC, surface firmness and putting green speed were recorded each week and pooled by month. Soil VWC in the top 1.5 inches (3.8 centimeters) was measured using a FieldScout TDR 300 (Spectrum Technologies) with 1.5-inch (3.8-centimeter) rods. Surface firmness was measured using a FieldScout TruFirm turf firmness meter (Spectrum Technologies). Soil VWC and firmness were recorded as the average of three random locations inside each plot. Surface firmness data were transformed by subtracting the instrument reading from the maximum possible reading (1.5 inch); thus, greater numbers represented greater firmness. Putting green speed was measured using the half-distance notch of a Stimpmeter. Putting green speed was recorded as the average of three balls rolled in the same direction and three balls rolled in the opposite direction.

Putting greens were maintained according to industry-standard management practices for an average public golf course in Florida with a modest budget. These practices included aerification, topdressing and verticutting. Turfgrass was mowed five to six days each week at a height of cut of 0.120 inch (3.048 millimeters) using a Toro Greensmaster 3150. Irrigation supplied water to the turfgrass at a volume approximately 80% of the previous week’s reference evapotranspiration (ET). The 80% reference ET threshold was chosen to minimize turfgrass stress without applying excessive water. Irrigation was suspended for 24 hours when rainfall exceeded 0.25 inch (0.64 centimeters) during any 24-hour period. Pesticides were applied as needed to minimize pest damage. Nitrogen, phosphorus and potassium were applied 12-2-12 at a nitrogen rate of 0.25 pound (113.4 grams) of nitrogen per week from January through December in Fort Lauderdale and from May through November in Jay. Trinexapac-ethyl (Primo Maxx, Syngenta) at 2 fluid ounces/acre (146 milliliters/hectare) was applied on June 1 and Aug. 3 in Fort Lauderdale.

In September 2018, Tropical Storm Gordon made landfall near Jay, producing an opportunity for us to investigate an additional objective. Heavy rainfall, tropical storms and hurricanes are common along the Atlantic and Gulf coasts. As a result, superintendents may use wetting agents to increase the downward movement of water in an attempt to facilitate putting green surface drying.

Anecdotes surrounding this practice abound, but supporting evidence is scant. Therefore, our second objective was to determine the influence of wetting agents on putting green moisture and firmness following a tropical storm. Data collected during the week of Tropical Storm Gordon and the following two weeks were pooled by week, and data from the remainder of the study were pooled by month.

Results

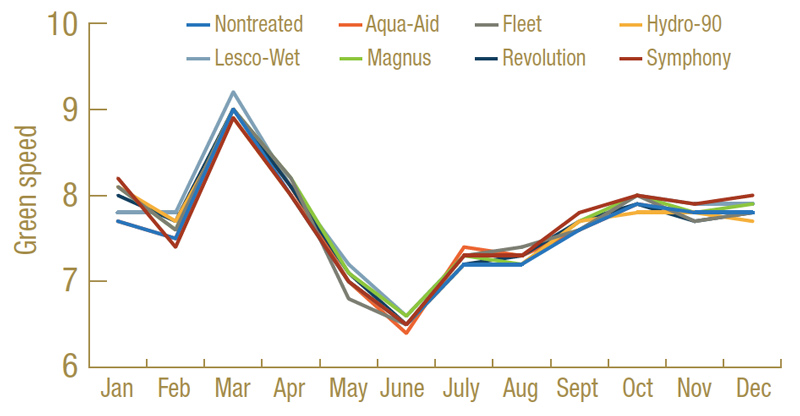

In Fort Lauderdale, wetting agents resulted in similar VWC as non-treated turfgrass during eight months, and some wetting agents reduced VWC during the remaining four months (Table 2). In February, Fleet, Hydro-90 and Revolution reduced VWC by 10% when compared with non-treated turfgrass. In September, Aqua-Aid, Fleet, Revolution and Symphony resulted in a 14% reduction in VWC relative to non-treated turfgrass. Fleet and Symphony reduced VWC by 15% in November and by 10% in December compared with non-treated turfgrass. The reduction in VWC did not result in a corresponding change in surface firmness or putting green speed at any point in the study. Wetting agents did not influence firmness or putting green speed.

Figure 1. TifEagle putting green speed as influenced by wetting agents in Fort Lauderdale, Fla., in 2018. Wetting agents did not influence putting green speeds compared with non-treated turfgrass during any month.

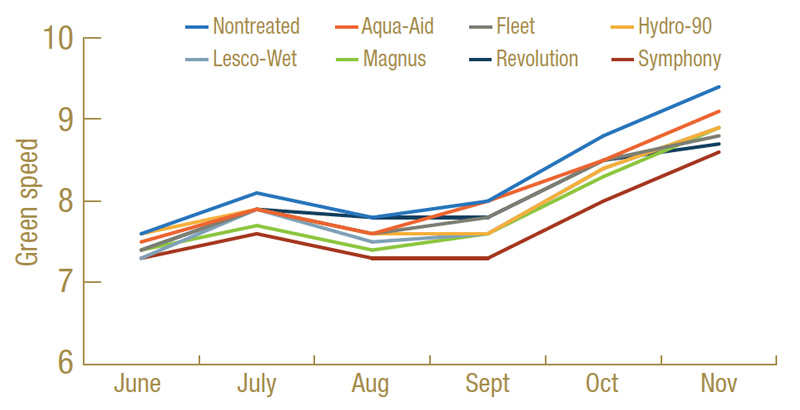

Figure 2. TifEagle putting green speed as influenced by wetting agents in Jay, Fla., in 2018. Wetting agents did not influence putting green speeds compared with non-treated turfgrass during any month.

During five of the six months of the North Florida study, wetting agents resulted in similar VWC to non-treated turfgrass (Table 3). However, during October, Lesco-Wet reduced VWC by 12% compared with non-treated turfgrass. As in Fort Lauderdale, this reduction in VWC did not influence firmness or putting green speed. Wetting agents resulted in similar firmness compared with non-treated turfgrass during June through September. Symphony reduced firmness by 5% in October and by 8% in November when compared with non-treated turfgrass. Putting green speed was unaffected by wetting agents throughout the study.

Tropical Storm Gordon produced approximately 6 inches of rain in less than 24 hours on Sept. 4 and 5 (Table 4). Volumetric water content during the week of the storm and during the two weeks following the storm remained unaffected by wetting agents. Symphony led to a 6% reduction in surface firmness compared with Aqua-Aid, Lesco-Wet and Magnus. No wetting agent influenced surface firmness compared with non-treated turfgrass during or immediately after the storm.

Discussion

Wetting agents did not influence VWC during the majority of months in Jay and Fort Lauderdale, and during the remaining months, wetting agent application resulted in a 10% to 15% reduction in VWC compared with non-treated turfgrass. Numerous studies have reported that wetting agents do not influence VWC on putting greens unless moisture is deficient (1, 7). Deficient moisture may lead to localized dry spots and increases the conditions that favor water repellency (8).

Because our study was irrigated in a manner consistent with best management practices, moisture deprivation was minimized, and the influence of wetting agents was likely also minimized. Thus, these results indicate that wetting agents applied to turfgrass maintained under sufficient irrigation may provide little benefit to VWC. It should be noted that this study measured the average VWC and did not measure VWC uniformity.

On the occasions that wetting agents influenced VWC, VWC was reduced in the top 1.5 inches compared with non-treated turfgrass. An increase in VWC in the top 1.5 inches relative to non-treated turfgrass was never measured using either the monthly pooled averages or the weekly averages (weekly data not shown). These results contradict claims that “retaining” wetting agents may increase the water-holding capacity at the surface compared with non-treated turfgrass. These results are supported by prior research that also found no evidence that wetting agents result in increased moisture in the surface of a sand-based root zone (5). These results suggest that, regardless of wetting agent chemistry, applying wetting agents to sand-based putting greens either does not affect VWC in the top 1.5 inches or causes it to decline; it will not likely increase.

Wetting agents did not affect surface firmness in any month in Fort Lauderdale. Firmness was affected only during October and November in Jay, when Symphony resulted in an approximately 8% softer surface compared with non-treated turfgrass. The cause of this reduction in firmness remains unknown. It may be presumed that the reduction was a result of increased moisture at the surface, but VWC indicated that the moisture was equivalent for non-treated turfgrass and turfgrass treated with Symphony.

Putting green speed was not affected by wetting agents during any month at either study location. Correspondingly, wetting agents never increased surface firmness. Thus, it may stand to reason that wetting agents did not increase putting green speeds because they did not increase surface firmness.

Editor’s note: Researchers explored whether applying wetting agents to dormant ultradwarf bermudagrass greens could curb winter injury and ensure speedy spring green-up. Read their findings in Wetting agents for winter turf protection.

Rainfall from Tropical Storm Gordon essentially saturated the putting green in Jay for nearly 24 hours — the VWC exceeded 85%. Turfgrass growing under saturated conditions is subject to various stresses associated with anaerobic conditions. A decline in turfgrass health is inevitable if the soil moisture does not decline rapidly. However, this study did not find any evidence that soil moisture in the top 1.5 inches could be reduced more rapidly by using wetting agents.

Summary: Wetting agents and green speed

This study found no evidence supporting the claims that wetting agents may result in “fast and firm” putting greens. This study was conducted on TifEagle putting greens that were not known to be hydrophobic or moisture-deprived and were maintained using management practices that commonly occur on Florida golf courses that have a modest budget. Under these conditions, wetting agents occasionally reduced moisture in the top 1.5 inches, but this occurred with wetting agents marketed as penetrants and those marketed as retainers. Wetting agents never increased moisture at the surface, increased firmness or produced faster greens compared with non-treated turf.

The extensive amount of prior wetting agent research clearly shows that wetting agents are valuable components of turfgrass management programs, particularly when soils are hydrophobic. However, superintendents who find themselves managing TifEagle greens under similar conditions (that is, adequate moisture and speeds of 7 to 10 feet) should not expect to increase firmness or speeds by using the wetting agents investigated in this study. However, investigating the influence of wetting agents on putting greens with different turfgrass species (particularly cool-season grasses) and/or maintained with speeds exceeding 10 feet was beyond the limits of this study and may warrant further investigation.

Following soil saturation from Tropical Storm Gordon, wetting agents did not reduce surface moisture or increase surface firmness compared with non-treated turfgrass. Superintendents interested in hastening surface drying following a tropical storm may be best served by allowing the green to drain and dry out on its own given the lack of evidence supporting the use of wetting agents for this purpose.

Further reading

The scientific article published about this research is “Do wetting agents influence golf ball roll distance?” by T.W. Shaddox and J.B. Unruh, published in HortTechnology 30(3):404-410. It is available at no cost at https://doi.org/10.21273/HORTTECH04576-20.

The research says ...

- TifEagle putting greens maintained to standards of Florida golf courses with a modest budget were treated with seven wetting agents to determine whether the products affected green speed.

- The wetting agents did not increase surface moisture, putting green speed or surface firmness at either location when compared with the non-treated control.

- A tropical storm that allowed researchers to test whether wetting agents reduced surface moisture showed that the products did not hasten drying of the turf surface.

- Investigating the effect of wetting agents on greens that have other grass species, especially cool-season grasses, and/or that are maintained with speeds exceeding 10 feet might produce different results.

Literature cited

- Bauer, S.J., M.J. Cavanaugh and B.P. Horgan. 2017. Wetting agent influence on putting green surface firmness. International Turfgrass Society Research Journal 13:624-628.

- Bosland, W., O. Idowu, B. Leinauer, M. Serena, M. Omer and D. Pruitt. 2019. Soil and plant health as affected by surfactants. ASA, CSSA and SSSA International Annual Meetings, San Antonio, Texas. ASA, CSSA and SSSA, Madison, Wis.

- Griffin, W., M. Habteselassie and P. Raymer. 2019. Impacts of turf care products on soil biological health. ASA, CSSA and SSSA International Annual Meetings, San Antonio, Texas. ASA, CSSA and SSSA, Madison, Wis.

- Hutchens, W., T. Gannon, D. Shew, K. Ahmed and J. Kerns. 2020. Golfdom 76:(February):44-46.

- Leinauer, B., and R.M. Sallenave. 2001. Effects of soil surfactants on water retention in turfgrass rootzones. International Turfgrass Society Research Journal 9:542-547.

- Linde, D.T., L.J. Stowell, W. Gelernter and K. McAuliffe. 2011. Monitoring and managing putting green firmness on golf courses. Applied Turfgrass Science 8(1) (https://doi.org/10.1094/ATS-2011-0126-01-RS).

- Lyons, E.M., K.S. Jordan and K. Carey. 2009. Use of wetting agents to relieve hydrophobicity in sand rootzone putting greens in a temperate climate zone. International Turfgrass Society Research Journal 11:1131-1138.

- Soldat, D.J., B. Lowery and W.R. Kussow. 2010. Surfactants increase uniformity of soil water content and reduce water repellency on sand-based golf putting greens. Soil Science 175(3):111-117 (https://doi.org/10.1097/SS.0b013e3181d6fa02).

Travis Shaddox is an assistant professor at the University of Kentucky, Lexington, Ky. J. Bryan Unruh is a professor and associate center director at the University of Florida, Jay, Fla.