Editor's note: Join J. Bryan Unruh, Ph.D., University of Florida, and Darren J. Davis, CGCS, GCSAA Past President, online on February 28 for a free GCSAA webinar: El Niño’s Effect in Florida: Explaining It To Your Golfers, Boards and Owners to learn more about this topic.

Olde Florida Golf Club is one of several South Florida golf courses dealing with adverse playing conditions as a result of El Niño-related weather patterns. Photos by Darren Davis

J. Bryan Unruh, Ph.D., has seen and heard all about the deleterious short-term effects of the climatic El Niño on South Florida golf courses.

When it comes to the more chilling long-term effects, he can’t help but think of the San Francisco 49ers.

“Are superintendents going to lose their jobs? That’s typically what happens,” says Unruh, a turfgrass scientist and associate director of the University of Florida/Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences West Florida Research and

Education Center. “These conditions are affecting everybody, but unreasonable expectations come into play. I’m not aware at the moment of anybody who’s lost their job, but you know the team that lost the Super Bowl? A lot of coaches

got fired. It didn’t matter that they were the second-best team.”

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration defines El Niño as the warm phase of the El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO) cycle, a complicated and interconnected variation in sea temperatures, rainfall, air pressure and atmospheric

circulation across the equatorial Pacific Ocean. El Niño is the above-average sea-surface temperature that develops, while La Niña, the periodic cooling of sea temperatures, is the cold phase of the ENSO cycle.

El Niño and La Niña episodes occur roughly every three to five years, NOAA says.

While they can affect weather globally, by the time the effects of El Niño reach South Florida, the resultant risks of increased precipitation, below-average temperatures and increased clouds hit the area hard — at a time when the local golf

industry is at its most vulnerable.

El Niño effects tend to strike South Florida right in the middle of the golf season.

“One of the key points that’s often missed is that winters in South Florida are already very stressful for bermudagrass and warm-season grasses in general,” says Unruh, a 34-year Educator member of GCSAA and the association’s 2023

winner of the President’s Award for Environmental Stewardship. “Water, light, temperature, nutrition, in that order, are the key drivers for turfgrass health. When you get south of Orlando, even in a normal year, the day lengths get short.

Temperatures are on the cooler side for warm-season turfgrasses. Then you have all these snowbirds flocking to Florida to play golf. You create a very artificial system on turfgrasses that want to go to bed for winter. Growth is slow. Then we dump

a lot of golfers on top of it. It’s normally stressed, then you throw an El Niño year on top of water, light, temperature, nutrition, and the wheels on the bus get a little wobbly.”

If they don’t fall right off altogether.

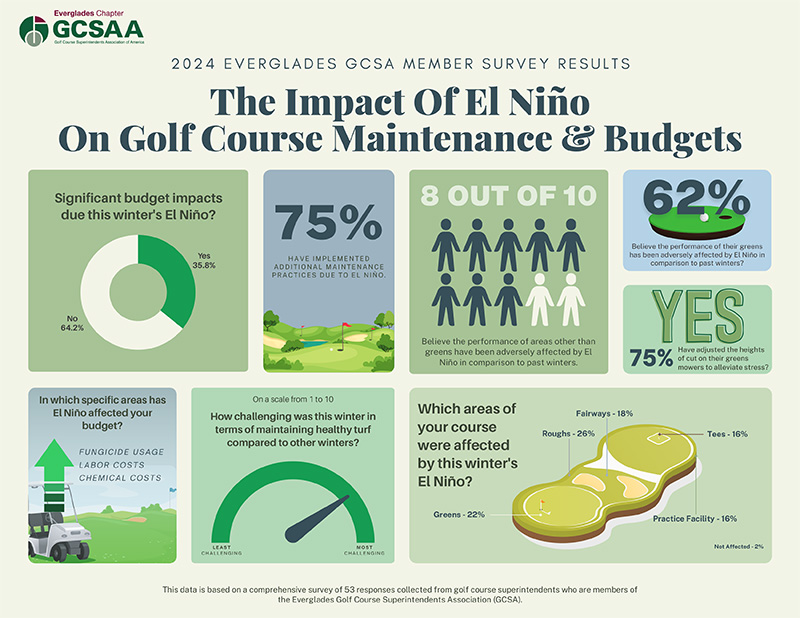

The Everglades GCSA conducted a member survey that found, in part:

- 35.8% of its members felt a significant impact to their budgets due to El Niño.

- 75% implemented additional maintenance practices due to El Niño.

- 62% said El Niño adversely affected the performance of their greens.

- 75% said they had adjusted height-of-cut on greens to alleviate stress.

El Niño wasn’t a surprise. NOAA projected as far back as summer 2023 that there was a 55% chance for a “strong” El Niño and a 35% chance it could become one of the most intense ever.

Michelle L’Heureux, lead ENSO forecaster for the National Weather Service’s Climate Prediction Center, points out not all El Niño effects are negative. In the northern U.S., for instance, it can result in warmer-than-average conditions,

which can lower heating bills.

“It depends on your context and focus,” she said. “In terms of ranking, this event appears to be ranked about the fifth-strongest El Niño going back to 1950. I’m basing this on the sea-surface temperature anomalies in the

east-central equatorial Pacific, but there are other ways to rank El Niño.”

Regardless of its ranking, its arrival was preceded by another weather anomaly that made it even more difficult to prepare for. Two regions in South Florida barely 100 miles apart went through drastically different precipitation periods. While the west

coast of Florida near Naples recorded its driest year in 2023, the Fort Lauderdale area 100-some miles east had its wettest year on record. One dealt with drought, the other deluge, all while trying to prepare their courses to be at their healthiest

to survive El Niño.

The cover story on the just-published Winter 2024 edition of Florida Turf Digest blared, ”El Niño wreaks havoc on golf courses and sports fields,” and it wasn’t sensationalism.

“This was just the perfect storm with the crazy conditions we’ve had in 2023,” Unruh says.

Here’s what some superintendents in South Florida have seen and heard — and what they’ve done to weather El Niño.

Darren Davis says the use of solid-tine aeration and the Hydroject (pictured) was critical this winter to increase oxygen in the soil.

The blogfather

Whenever and wherever golf maintenance workers in South Florida gathered this winter, El Niño was sure to come up. When it did, a couple of blogs by Darren Davis, CGCS, were sure to be mentioned as well.

The first was “El Niño and its effect on turfgrass management,” posted just after the first of the year. The sequel was February’s “How does turfgrass eat? (El Niño Part 2).” Together, they provide a primer

on El Niño and how it uniquely affects South Florida, as seen through the eyes of a veteran South Florida superintendent.

“We’ve had our hand on the wheel at 10 and 2 all winter,” says Davis, a 34-year association member and 2018 past president who, if turfgrass communication had a patron saint, would have his face on the medallion. “Normally, you’re

worried about cart traffic and all that, but this year is just different. With your fungicides, plant protectants, you have to be on your A game. I hadn’t seen Pythium in 31 years here, and now we had to treat for Pythium. Fungicide expenditures

are going to be very high this year. Any weakness — traffic, disease, divot recovery — so many things need growth for recovery, and it’s just not there this year.”

Davis is unequivocal in describing this winter’s El Niño effects.

“Worst winter in 31 years,” he says. “We managed differently this year than any of the 31 years I’ve been here. You know, you hear about El Niño and La Niña frequently, but it’s just a prediction. It’s

a forecast, and, as you know, forecasts aren’t always accurate. You tend to get a little jaded. But this is the real deal. And what made it worse was, we were coming off three La Niña winters in a row, and this is one of the strongest

El Niño patterns we’ve had, and we’ve had to do things differently from the ways we’ve done them before. It was just the perfect storm.”

Crucial to weathering the El Niño storm was preparation. Having learned the long-range forecast for a potent El Niño and having experienced a few in his tenure, Davis ensured his offseason prep — which in his part of Florida peaks

in the summer, when much of South Florida “looks like a ghost town,” as Unruh describes it as the snowbirds flock back north — keyed on plant health.

“You have to go into the season healthy. As superintendents, you want to provide a good-looking golf course that provides the conditions your golfers want,” Davis says. “That can be something of a balance. Some golfers want fast greens.

That means a low height of cut, double-cutting and rolling. The challenge this year was, we just wanted to keep grass on the greens.

“It’s a balance of providing quality playing conditions with aesthetics. You want to go in strong. If you went into December a little weak, you struggled, and I know a lot of people who struggled.”

Davis admits he worried about those who struggled — and especially for those who didn’t forewarn their stakeholders that such struggles were imminent.

“This year it was critical to communicate,” Davis says. “Members need to understand the facts. You’re not making excuses. You’re just explaining the facts of the weather. A superintendent must have a trust level with the

membership. And it’s important to be seen. It’s a lot easier to be fired if you’re not known by the membership. If you’re known and trusted, you can get through tough times.”

At the Country Club of Naples, bad weather has been an issue for the course's young grasses following a renovation last summer. Photo by Billy Davidson

Video FTW

Just a few miles west of Davis’ Olde Florida Golf Club — where the turfgrasses are as mature as the facility’s name would suggest, the Country Club of Naples has the opposite problem.

CCN wrapped up a large renovation last summer, meaning some of the grasses there are barely 6 months old.

“So far, my membership seems to appreciate the communication,” says Country Club of Naples superintendent Billy Davidson, CGCS, a 31-year association member. “They’ve been understanding because we got out early, playing offense

with the message. It’s difficult, because we just spent $8 million to rebuild the golf course, and expectations are off the charts. But I give a lot of credit to our very effective outgoing communications pieces from the golf maintenance department,

where we explain if we step onto the grass too quickly, we could run the golf course to death. They’re champing at the bit for things to make the turn, but they’re also understanding that, if we don’t do it correctly, there could

be detrimental effects.”

Two crucial pieces of that outgoing communication were a pair of videos by Davidson. The first, “El Niño effect,” was posted Jan. 8. In

it, Davidson walks on the course a bit explaining why the grasses look “pukey.” The second, “El Niño, its effect on golf courses and how superintendents are dealing with it,”

went up a week later. Davidson used ChatGPT to write a script conforming to prompts addressed in the title. He then used an AI-driven voice generator to read the script in the voice of Sir David Attenborough, the famed British broadcaster.

“It turned out pretty cool” Davidson says of the 6½-minute video that has been viewed more than 3,000 times on YouTube. “We’re just trying to do a lot of education. You can put out as much extra fertilizer as you want. If

you don’t have any sun, it doesn’t matter. It’s all about the education, trying to create tolerance and understanding. We have been trying to create awareness of what’s going on, to get them to understand we just have to suffer

this year. It has been a fruitful endeavor for me to get them to be OK with a little lesser quality than they’re used to. There’s just no getting around that.”

Davidson has a secret weapon to make sure the message is being received.

“If you want to know what’s going on with the golf course, talk to a teaching pro,” he says. “Teaching pros are like hairdressers. If you want to know what’s going on, you go talk to them. They tell me people aren’t

complaining about the golf course. They’re complaining about the weather. They all wish it (the course) was better, but they all understand. That tells you you’ve done a good job communicating with them about what’s going on and

the reasons why. They see it anyway. You might as well tell ‘em what’s going on, good or bad.”

Going into winter, the crew at CCN raised fairway mowing heights from 3/8-inch to ½ and roughs from 1¼ inch to 1½.

“There’s just no growth, and with no growth, there’s no recovery,” Davidson says. “Our roughs get pretty beat up anyway, but it’s just the death of a thousand razor blades.”

Fluctuating temperatures have caused increased root rot at the The Bridges at Springtree Golf Club in Sunrise, Fla. Photo by John Glomski

“The perfect situation for disease’

For John Glomski, a relative newcomer to Florida, El Niño translates into one word.

“Disease, disease, disease,” says Glomski, superintendent at The Bridges at Springtree Golf Club in Sunrise. “That’s my big thing. It’s been a wet winter, then hot, then cold, then hot, back and forth. It’ll be nice

and warm, 70 or 80, then we’ll get a bunch of rain. It’ll drop into the 40s in the morning. It’s the perfect situation for disease.”

While Naples, some 100 miles away on Florida’s west coast, suffered its driest 2023 on record, Sunrise — a Fort Lauderdale suburb on the east coast — had its wettest year on record. As a result, Glomski, a four-year GCSAA member, had

to increase fungicide applications significantly.

“We see a lot of dollar spot normally, and we take care of that,” he says. “But a month ago, we started to see some sort of root rot everywhere, so we had to spray, and it has to get watered in. It’s a real pain having to spray

everything and make sure it’s watered in since this is our busiest time of year.”

In some ways, The Bridges at Springtree has dodged a bit of El Niño’s bullet. Because it’s grassed with paspalum, it hasn’t suffered the yellowing that’s typical of sun-starved bermudagrasses.

“Even with the weather, we didn’t lose much color,” Glomski says. “But our tees, with all the divots … you can definitely see it’s taking a long time to grow in. We had to shut down a couple of tees to allow them time

to heal up.”

In addition, Glomski and his small crew — two full-time employees, four part-timers — tending the small 45-acre facility have had to enforce several cart-path-only restrictions and raised the height of cut on greens and tees.

“That’s not that out of the ordinary,” Glomski says. “I’m just not mowing as much as last year. Either it’s wet or it’s cold and the grass isn’t growing. Last year, I was mowing tees and fairways at least

once, twice a week. I think I’ve gone at least two weeks without having to mow either.”

This was Glomski’s first experience with a strong El Niño winter.

“I’ve only been in Florida for five years or so,” he says. “I’d never heard of El Niño until I came in one day and one of the workers said, ‘Oh, yeah, it’ll be an El Niño year. I didn’t know

what in the hell that meant. I know now.”

Everglades GCSA's infographic detailing the weather's impact on member's courses and operations. Image courtesy of Everglades GCSA

Foresight is 20-20

Gabe Gallo knew this was coming.

Having experienced the most recent strong El Niño pattern to meddle with South Florida as an assistant in 2016, Gallo had this on his radar just as soon as it was on the NOAA’s.

“We knew this was coming back in the summer,” says Gallo, GCSAA Class A director of Agronomy at Fiddlesticks Country Club in Fort Myers, Fla., and 16-year association member. “I think a lot of superintendents did a good job of communication.

I got it in my green committee minutes as early as June. That’s when we were first talking about this. We just wanted to caution the membership, to let them know what was coming.”

Gallo says he recalls 2016’s El Niño repercussions being more dire, especially on greens, but that might be because raising height-of-cut there was one of his first remediation efforts this time around.

“We’ve had some challenges,” Gallo says. “I’d say the greens, for me, weren’t so bad compared to 2016. But cart traffic and everything else — divots not knitting in, heavier ball marks on the greens — are

pretty similar. We had cloud cover for a whole lot longer. Cart traffic is probably the worst of everything and divots on the par 3s. You can only move so much. We’re recovering. We’ve been lucky the past couple of weeks, but it got scary

there for a bit.”

Though he did get in front of El Niño with his members, Gallo regrets not being entirely clear in his communication.

“For the most part, they’ve been very understanding,” he says of his golfers. “The biggest change to them, which I didn’t realize, was that maybe the speeds of the greens aren’t as fast. We just couldn’t get the

moisture out, that and the height of cut. I think that was the biggest shocker to them. Maybe I didn’t do as good of a job of communicating that as I should have. That’s something I’ve learned from all this.”

The sun’ll come out …

There might be (sun)light at the end of this tunnel.

The NOAA/National Weather Service Climate Prediction Center predicts a transition from El Niño to a neutral ENSO cycle is likely (79% chance) by April-June, with a 55% chance of a warmer, drier La Niña by June-August.

Regardless of the ENSO cycle, the winter solstice is past for the northern hemisphere, so days will continue to grow longer.

“Days are getting longer. Temperatures are going to come back. We’re starting to have more favorable conditions as we stretch into spring,” Unruh says.

In Davis’ mind, it has to get better, if only because it couldn’t get much worse.

“You have to be a happy person,” he says. “The good thing is, yes, we get an extra minute or two every day of sun. We’ll finish strong. I talked to a friend of mine who’s at a golf course that’s struggling. We were

commiserating. He said, ‘Darren, it’s gotta break at some point.’ I think we feel it starting to break.

“This is the week of our member-guest, and the weather broke enough I felt comfortable adjusting mowing heights, tightening it up. I saw a local meteorologist had his sun forecast. He titled it, ‘The sunniest week of winter.’ I just

smiled.”

Andrew Hartsock is GCM’s senior managing editor.