In a survey of U.S. golf courses conducted in 2022, respondents were asked to identify the percentage of turfgrass type by golf course feature. Courtesy photo

Comprehensive documentation of land-use characteristics on U.S. golf courses has occurred three times since 2006 via surveys conducted by GCSAA. The first survey, conducted in 2006 (19), established the golf course industry baseline from which data derived

from a subsequent longitudinal survey conducted in 2015 was compared (14). These surveys provided useful information on maintained turfgrass acreage (total and by course feature). A third survey was conducted in 2022, revealing that the projected

total acreage of U.S. golf facilities was 2,131,838 acres and the median acreage of an 18-hole golf facility was 146 acres (26). Of these 146 acres, approximately 60% are covered with turfgrass. Nationally in 2021, the land use of an 18-hole golf

facility was allocated as follows:

- 95 acres of maintained turfgrass.

- 49 acres of roughs.

- 27.1 acres of fairways.

- 5.9 acres of practice areas.

- 3.3 acres of greens.

- 3.1 acres of tees.

- 1.7 acres of clubhouse grounds.

- 0.8 acres of turfgrass nursery.

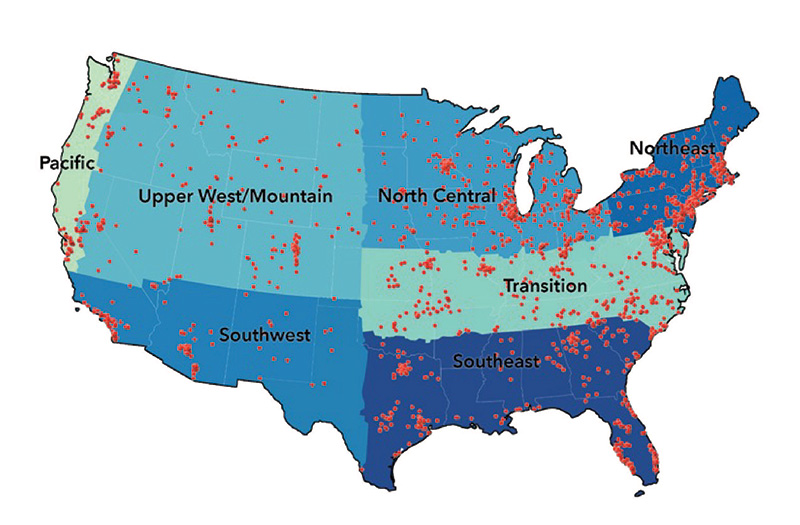

Figure 1. Geographic distribution of respondents to GCSAA's surveys and the designated agronomic regions.

Turfgrass species and/or cultivars vary greatly according to many variables, including climate, topography and budget. As these variables change, so may turfgrass selection, leading to changes in management practices, resource requirements, etc. Thus,

it is important to document the changes in turfgrasses being managed on U.S. golf facilities so that turfgrass managers, educators and policymakers can efficiently allocate resources and provide relevant best management practices.

The first two surveys provided projected and median values of turfgrass types (i.e., cool-season versus warm-season) and their relative distribution across the U.S. Although the projected and median values provide important information regarding turfgrasses

used on U.S. golf facilities, the sole use of projected and median values does not provide the precision necessary to determine if U.S. golf facilities are shifting their turfgrass selection. Determining the percentage of golf facilities that use

specific turfgrass types on each course feature would provide valuable information that has not been documented. Therefore, the objective of this survey was to garner a better understanding of turfgrass species use by measuring the percentage of U.S.

golf facilities that reported having specific turfgrass species by region and by course features and to elucidate changes in species selection that have occurred since 2005.

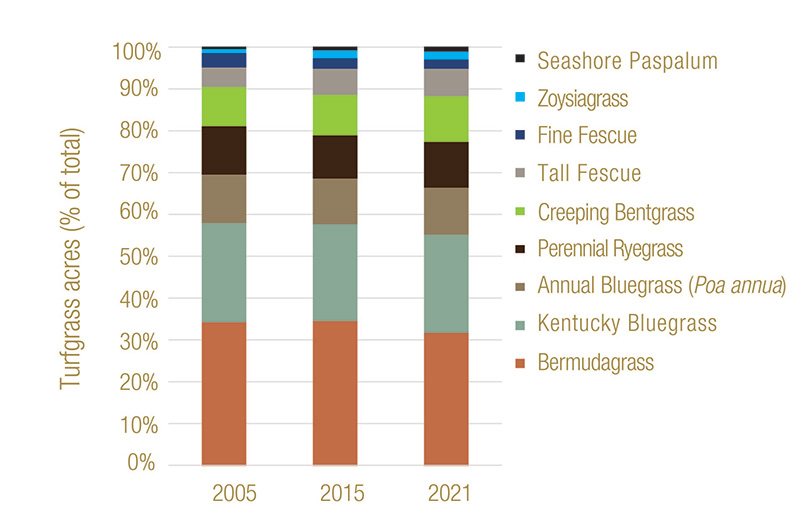

Figure 2. Turfgrass types as a percentage of total turfgrass acres on U.S. golf facilities in 2005, 2015 and 2021.

Methodology

A survey with questions identical to those used in the first two surveys was distributed electronically via electronic mailing lists of the National Golf Foundation (Jupiter, Fla.) and GCSAA to 13,938 unique golf facilities. The survey was opened on Sept.

1, 2022, and closed on Oct. 17, 2022, and respondents’ names remained anonymous. The turfgrass-use data were merged with the data from 2005 and 2015, which allowed for comparison of years. Responses were received from 1,861 golf facilities,

which was 13.3% of the known U.S. total.

Respondents were asked to identify the percentage of turfgrass type by golf course feature. Turfgrass types were creeping bentgrass (Agrostis stolonifera L.), Kentucky bluegrass (Poa pratensis L.), annual bluegrass (Poa annua L.), perennial ryegrass (Lolium

perenne L.), tall fescue (Festuca arundinacea Schreb.), fine fescue (F. spp.), bermudagrass (Cynodon spp.), zoysiagrass (Zoysia spp.), seashore paspalum (Paspalum vaginatum Swartz) and buffalograss [Buchloë dactyloides (Nutt.) Engelm.]. Golf

course features were tees, putting greens, fairways, roughs, practice areas and nurseries. Responses were stratified according to their agronomic region (Figure 1) and weighted to provide a valid representation of U.S. golf facilities, and appropriate

statistical procedures were followed (26).

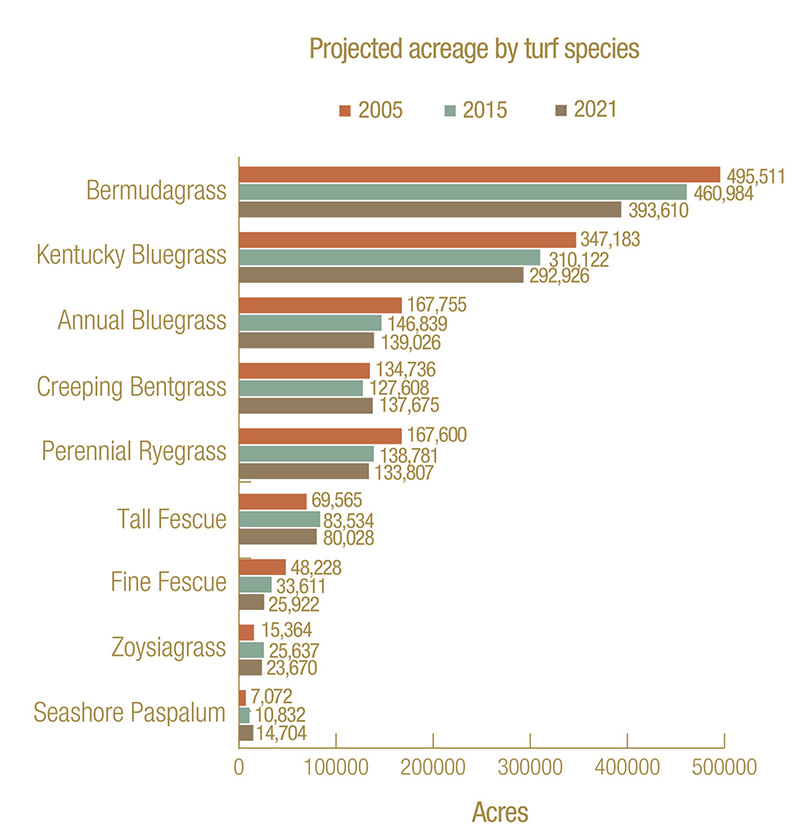

Figure 3. Projected percentage of turfgrass types on U.S. golf facilities in 2005, 2015 and 2021.

Results

Turfgrass species by region

Bermudagrass accounts for approximately one-third of the total maintained turfgrass on U.S. golf facilities and has been so since 2005 (Figure 2). Bermudagrass accounted for 393,610 acres of turfgrass on U.S. golf facilities in 2021, a reduction of 21%

since 2005 (Figure 3). This reduction is likely a result of course closures (26). Of the total acres of bermudagrass on U.S. golf facilities, 58% was reported in the Southeast region. The greatest percent reduction of bermudagrass acreage was reported

in the Upper West/Mountain (UWM) region (56%), whereas the only region that reported an increase in bermudagrass acreage was the Pacific region (30%).

Kentucky bluegrass was the second-most-common turfgrass nationally, accounting for 24% of the total turfgrass acreage on U.S. golf facilities in 2021 and was the most common cool-season species (292,926 acres). The Southwest and UWM regions reported increases

in Kentucky bluegrass acreage from 2005 to 2021, whereas all other regions reported decreases varying from 10% in the Northeast to 88% in the Southeast. Collectively, the North Central, Northeast and UWM regions accounted for 90% of the total area

of Kentucky bluegrass on U.S. golf facilities.

Across the U.S., annual bluegrass was the third-most-abundantly used turfgrass on golf courses; however, the projected area decreased by 17% from 2005 to 2021 to 139,026 acres. Decreases between 2005 and 2021 were also reported within each region except

the UWM region, with the greatest percentage decrease occurring in the Southeast region (77%) and the greatest acreage decrease occurring in the North Central region (17,231 acres). The UWM region reported a 14.8% increase in annual bluegrass acreage.

The North Central and Northeast regions combined have 64% of the annual bluegrass acres.

Comprehensive documentation of land-use characteristics on U.S. golf courses has occurred three times since 2006 via surveys conducted by GCSAA. The three most commonly used turfgrass species are bermudagrass, Kentucky bluegrass and annual bluegrass. Photo by Roger Billings

Despite being listed as the most difficult weed to control and the third-most-common weed in turfgrass (30), annual bluegrass has been the third-most-abundant turfgrass grown on U.S. golf courses since 2005. The extensive reliance on herbicides for annual

bluegrass control has resulted in high levels of herbicide resistance in certain plant populations (15) and the belief that effective chemical control measures no longer exist (http://resistpoa.org/). In addition, although the Latin name “annua”

implies that the species is an annual, recent research supports the hypothesis that Poa annua (annual bluegrass) is of a perennial lifecycle and can be influenced by environmental conditions (4). Consequently, annual bluegrass prevalence on U.S. golf

courses is not likely to change in the foreseeable future.

The projected acreage of creeping bentgrass in 2021 was about equal to that reported in 2005. Like annual bluegrass, the majority (76%) of creeping bentgrass was in the North Central and Northeast regions. However, five of the seven regions reported an

increase in creeping bentgrass acres, and only the Southeast and Transition regions reported decreases of 35% and 22%, respectively. Creeping bentgrass, a cool-season turfgrass, has been used extensively across the U.S., especially on putting greens

(7). The popularity of creeping bentgrass use on putting greens may be a result of the reduced maintenance costs relative to other options such as annual bluegrass (1). However, cool-season turfgrass performance is affected by water availability and

temperature extremes. A long-term goal of turfgrass breeding programs is to improve drought and heat tolerance of creeping bentgrass (17, 18, 21, 29).

Perennial ryegrass consistently ranks the fifth-most-used species on U.S. golf courses, accounting for 6.3% of the total acreage in 2021. However, there were approximately 20% fewer acres of perennial ryegrass in 2021 than in 2005.

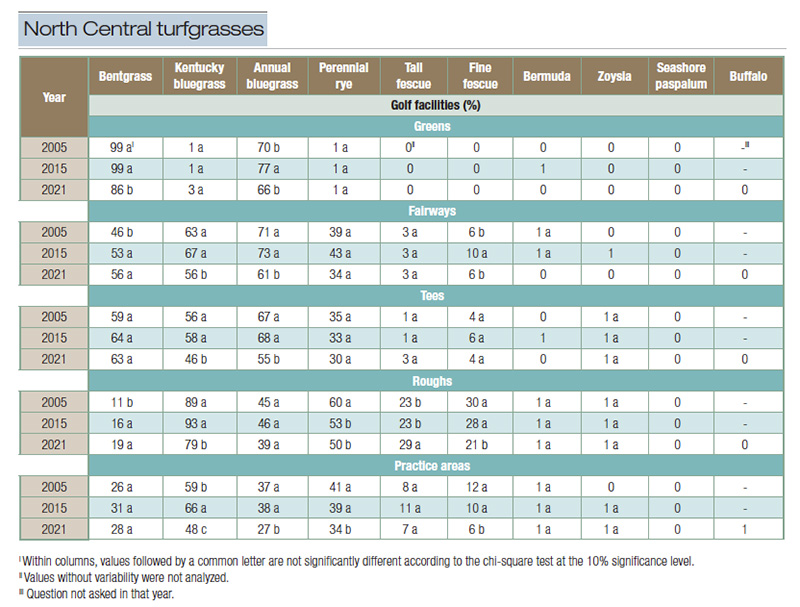

Table 1. Frequency of golf facilities in the U.S. North Central region that have the listed turfgrass species or cultivar on greens, fairways, tees, roughs or practice areas in 2005, 2015 and 2021.

Tall fescue was the second-least-common cool-season turfgrass used, but golf facilities reported having 15% more acres in 2021 than in 2005. Notable increases in tall fescue acreage were reported in the North Central region (32%) and Northeast region

(73%); however, all other regions reported reduced acreage. More than half of the tall fescue acres are in the Transition region.

Fine fescue was the least common cool-season turfgrass reported nationally in 2021 at 25,922 acres, a 46% reduction from 2005. The cause of this reduction is unknown, but is, at least in part, a result of golf course closures (26).

Of the cool-season turfgrasses, the fescues generally possess better overall drought resistance than other species, and tall fescue has good cold and heat tolerance, making it favorable in the Transition zone, where the severity of cool-season turfgrasses

injury resulting from extreme high temperatures and warm-season turfgrass injury resulting from extreme low temperatures often varies from one year to the next (13). Efforts toward lower input systems have led to the evaluation of fine fescues for

golf course use, but barriers to adoption remain (5, 23, 31).

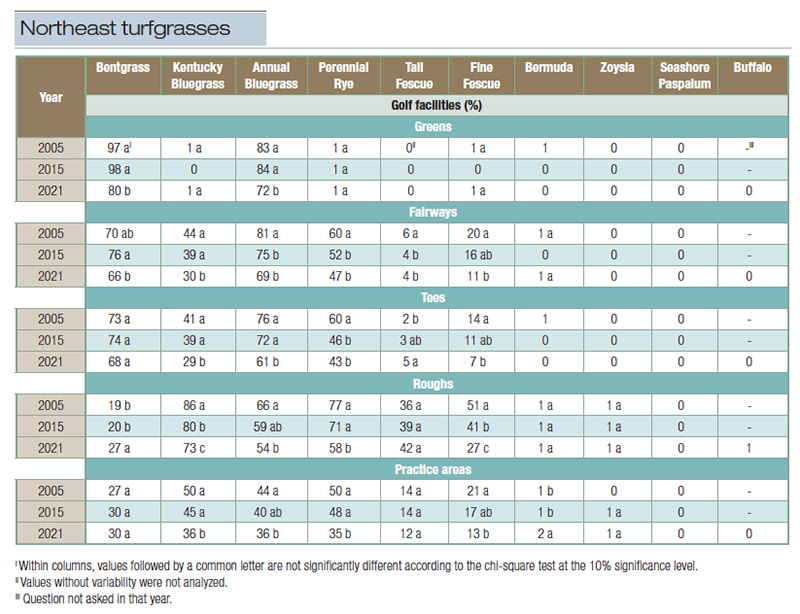

Table 2. Frequency of golf facilities in the U.S. Northeast region that have the listed turfgrass species or cultivar on greens, fairways, tees, roughs or practice areas in 2005, 2015 and 2021.

Nationally, zoysiagrass (23,670 acres) and seashore paspalum (14,704 acres) represented the fewest acres of all turfgrasses grown on U.S. golf facilities. However, the percentage increase in acres of zoysiagrass and seashore paspalum from 2005 to 2021

were 54% and 108%, respectively, which represented the greatest percent increases of any turfgrass nationally. Ninety-seven percent of all zoysiagrass acres are in the Southeast and Transition regions, whereas 99% of seashore paspalum acreage occurs

in the Southeast and Southwest regions.

Zoysiagrass acreage in the Southwest region increased nearly tenfold from 2005 to 2015, but in 2021 had 80% fewer acres than in 2005. Similarly, across the U.S. and in the Northeast and Transition regions, zoysiagrass acreage peaked in 2015 and declined

in 2021, yet remains greater than the 2005 baseline. The increase is likely associated with the increase in improved cultivars and increased sod availability in those regions (22). Despite the positive attributes of zoysiagrass, it has shortcomings

(22), some of which may have manifested in certain regions, resulting in the reduction of acreage. Today, public- and private-sector breeding programs are focused on understanding and improving the zoysiagrass germplasm (2, 20, 22).

Seashore paspalum generally lacks cold tolerance, thus limiting its adaptation to the warmer regions of the Southeast and Southwest (12). An advantage of using seashore paspalum is its ability to tolerate saline/sodic soils and poor water quality often

found in reclaimed water and coastal environments (i.e., Southeast region and California) (12). Eighty-seven percent of all reclaimed water use on golf facilities occurs in the Southeast and Southwest regions (25).

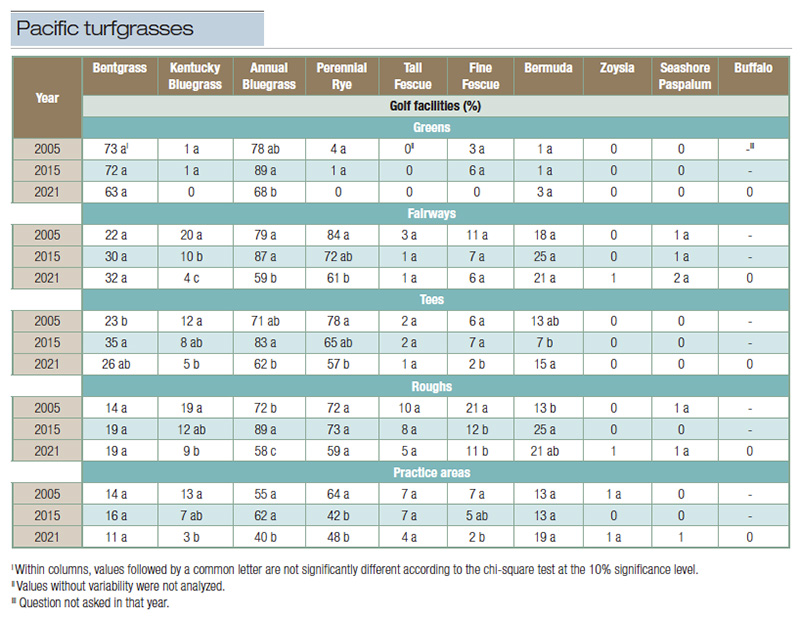

Table 3. Frequency of golf facilities in the U.S. Pacific region that have the listed turfgrass species or cultivar on greens, fairways, tees, roughs or practice areas in 2005, 2015 and 2021.

Turfgrass species by region and course feature

North Central region: The majority of turfgrasses were cool-season turfgrasses, and less than 1% of golf facilities reported having warm-season turfgrasses in 2005, 2015 and 2021 (Table 1). The percentage of golf facilities with bentgrass putting greens

declined to 86% from 2005 to 2021, whereas the percentage with annual bluegrass remained equivalent to 2005 at 66%. The frequency of bentgrass on fairways increased to 56% of golf facilities from 2005 to 2021, whereas Kentucky bluegrass and annual

bluegrass declined to 56% and 61%, respectively. Annual bluegrass was the most reported turfgrass on tees in 2005, but declined to 55% of facilities in 2021, resulting in bentgrass now being the most reported turfgrass on tees. The frequency of Kentucky

bluegrass on roughs declined to 79% of golf facilities from 2005 to 2021 but remained the most common turfgrass on roughs.

Northeast: Golf facilities consisted almost entirely of cool-season turfgrasses, with less than 2% of facilities having warm-season turfgrasses in 2021 (Table 2). Putting greens were primarily bentgrass or annual bluegrass in 2005, 2015 and 2021. Similar

percentages of golf facilities reported having the same turfgrasses on fairways and tees. Fairways and tees consisted primarily of bentgrass and annual bluegrass, followed by perennial ryegrass and Kentucky bluegrass between 2005 and 2021. Seventy-three

percent of golf facilities reported having Kentucky bluegrass in roughs in 2021, which was a decrease from 86% reported in 2005. Golf facilities reported having several cool-season turfgrasses in practice areas, with no single species being dominant.

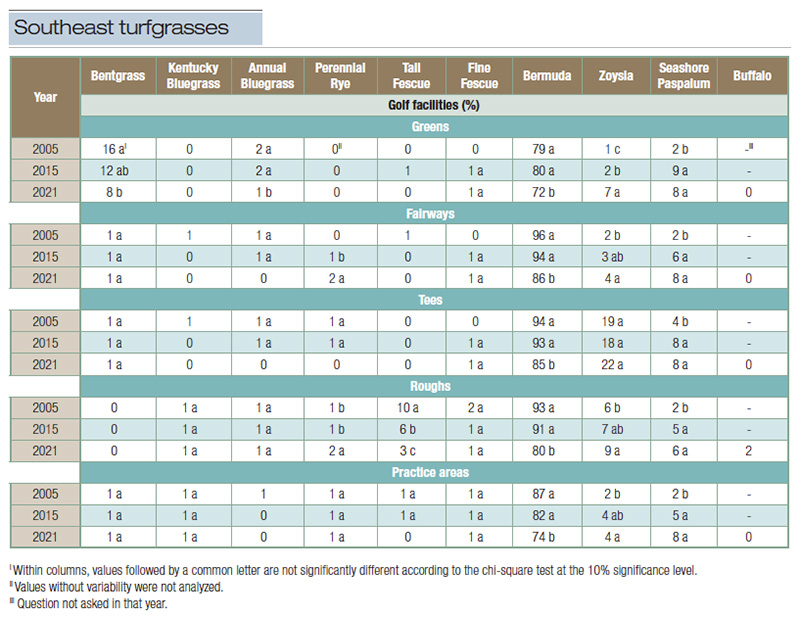

Table 4. Frequency of golf facilities in the U.S. Southeast region that have the listed turfgrass species or cultivar on greens, fairways, tees, roughs or practice areas in 2005, 2015 and 2021.

Pacific: Golf facilities reported having primarily cool-season turfgrasses, but as many as 21% reported using a warm-season turfgrass in fairways and roughs (Table 3). Putting greens were dominated by annual bluegrass and bentgrass, with 68% and 63% of

golf facilities, respectively, reporting their use in 2021. On fairways, tees, roughs and practices areas, golf facilities reported a consistent percentage of turfgrass use, with perennial ryegrass and annual bluegrass being the most common, followed

by bentgrass and bermudagrass.

Southeast: Warm-season turfgrasses were primarily used on each course feature from 2005 to 2021 (Table 4). The use of bermudagrass on putting greens decreased from 79% to 72% between 2005 and 2021, whereas the percentage of facilities that reported

using zoysiagrass and seashore paspalum increased to 7% and 8%, respectively. The percentage of golf facilities that reported having bentgrass on putting greens decreased from 16% to 8% between 2005 and 2021. The percentage of facilities that reported

using bermudagrass decreased on fairways, tees, roughs and practice areas between 2005 and 2021, whereas the use of seashore paspalum increased on each course feature. The increase in seashore paspalum mostly occurred before 2015, yet its use has

remained the same since then.

The significant increase in seashore paspalum occurred following an era in which much research was conducted on its culture and management (24, 28). The percentage of facilities that reported using zoysiagrass also increased between 2005 and 2021 on each

course feature except tees. A notable increase in zoysiagrass on golf course putting greens has occurred since 2005. This increase is likely attributed to the development of dense, fine textured cultivars and their suitability for putting green heights

of cut (6, 9, 10, 11).

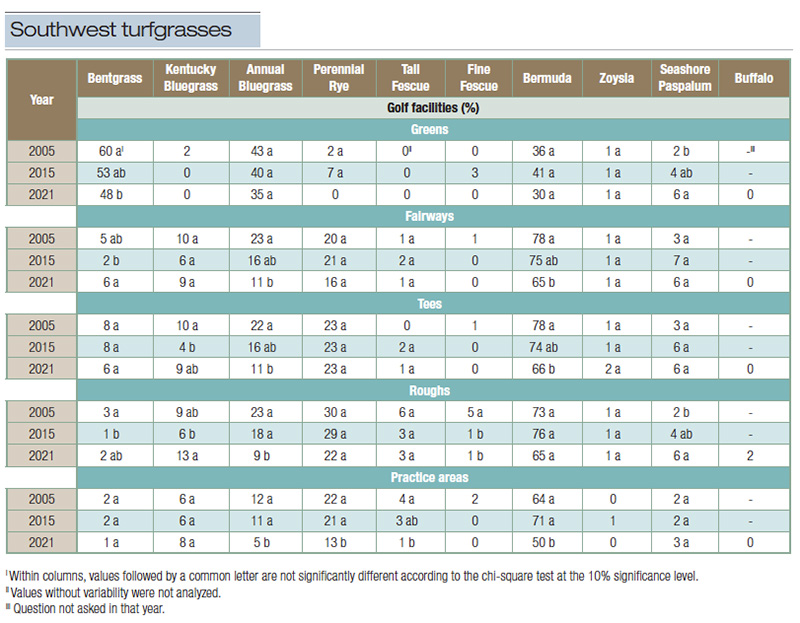

Table 5. Frequency of golf facilities in the U.S. Southwest region that have the listed turfgrass species or cultivar on greens, fairways, tees, roughs or practice areas in 2005, 2015 and 2021.

Southwest: Golf facilities reported using both cool- and warm-season turfgrasses, with bentgrass and annual bluegrass greens, and bermudagrass being most common on all remaining course features (Table 5). Although bentgrass was the most reported turfgrass

on putting greens, the frequency of use on golf facilities decreased from 60% to 48% between 2005 and 2021, respectively — a shift likely attributed to water scarcity issues in the Southwest region. The frequency of facilities that reported

using seashore paspalum on putting greens and in roughs increased to 6% in 2021. As noted previously, the use of reclaimed water in the Southwest region is common and bodes well for the irrigation of seashore paspalum.

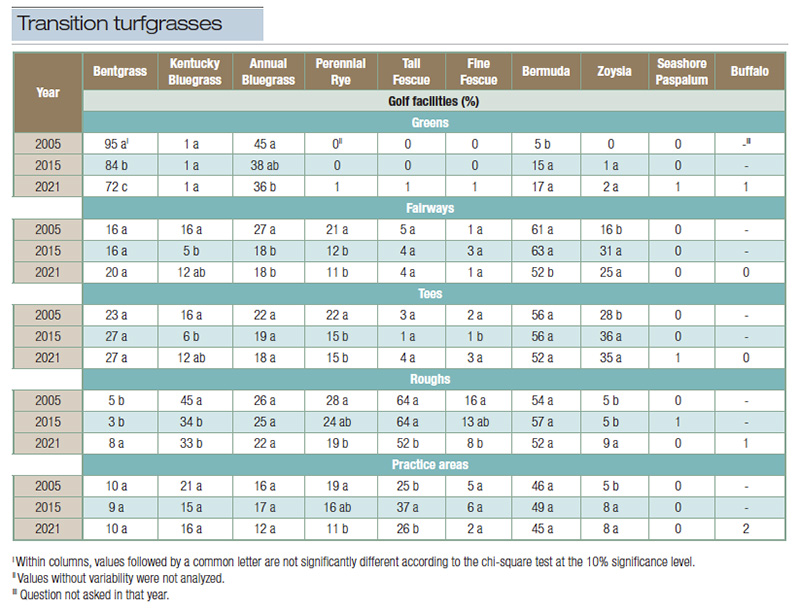

Transition: This region reported the most diverse use of turfgrasses (Table 6). The primary turfgrass reported on fairways, tees, roughs and practice areas was bermudagrass (45%-52%, depending on playing surface). Following bermudagrass, the next most

dominant fairway species were zoysiagrass, bentgrass and annual bluegrass at 25%, 20% and 18%, respectively. A mix of cool-season species was also reported on each course feature. Bentgrass and annual bluegrass were the dominant species on putting

greens, but their frequency decreased from 95% to 72% and from 45% to 36% between 2005 and 2021, respectively. The frequency of bermudagrass on putting greens increased from 5% to 17% from 2005 to 2021. Brosnan et al. (2022) reported that the distribution

of warm- and cool-season turfgrass species on putting greens across the U.S. differed from historical maps of growing zones and suggested that the shift could be associated with a changing climate (3). Nearly 87% of survey respondents in that report

indicated that winter protective covers were used to maintain bermudagrass putting greens, including 100% of respondents in the Transition region states of Kentucky, North Carolina, Tennessee and Virginia. These protective covers are typically used

when low-temperature injury is expected (8). The frequency of golf facilities in the Transition region using zoysiagrass on each course feature increased between 2005 and 2021.

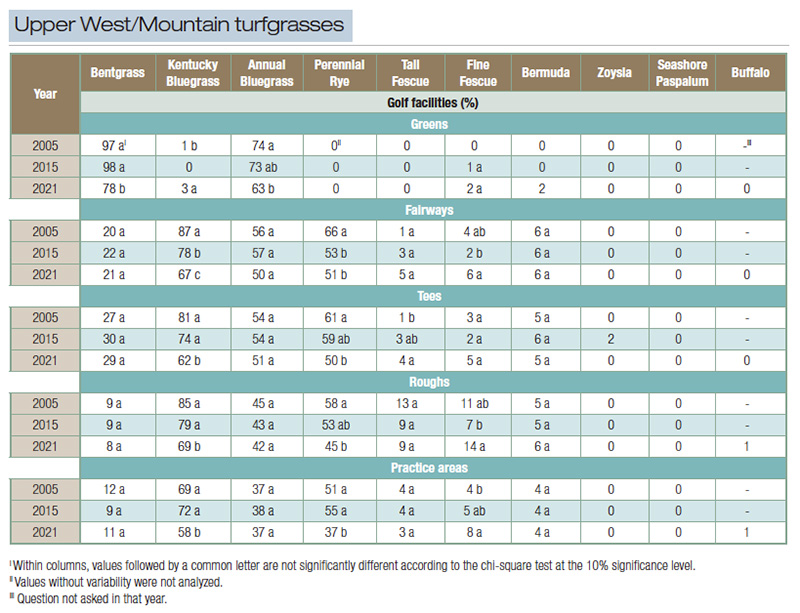

Upper West/Mountain: Cool-season turfgrasses are most used, with ≤ 6% reporting the use of warm-season turfgrasses (Table 7). Golf facilities reported using bentgrass and annual bluegrass most frequently on putting greens, and ≤ 3% of facilities

reported using other turfgrasses. The diversification of turfgrasses on all remaining course features was somewhat consistent, with Kentucky bluegrass being the most common, followed by annual bluegrass and perennial ryegrass.

Table 6. Frequency of golf facilities in the U.S. Transition region that have the listed turfgrass species or cultivar on greens, fairways, tees, roughs or practice areas in 2005, 2015 and 2021.

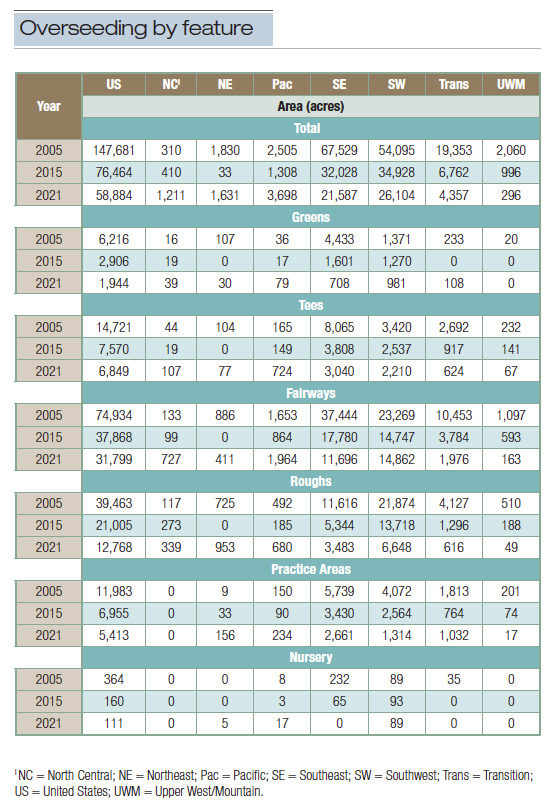

Winter overseeding

Overseeding warm-season turfgrasses with cool-season turfgrasses to provide temporary seasonal color decreased on U.S. golf facilities by 60% from 2005 to 2021 (147,681 acres to 58,884 acres) (Table 8). The decrease was reported on each course feature,

with 49% of the 88,797-acre reduction accounted for by fairways. Fairways and roughs accounted for 76% of the total overseeded acres on U.S. golf facilities in 2021. The North Central and Pacific regions reported an increase in overseeded acres, whereas

all other regions reported a decrease. Like 2005 and 2015, the Southeast and Southwest regions reported the greatest number of overseeded acres and together accounted for 81% of all the overseeded acres on U.S. golf facilities in 2021. However, both

the Southeast and Southwest regions reported the greatest reductions in overseeded acres from 2005 to 2021 at 45,942 and 27,991 acres, respectively. In the Southeast region, reductions in overseeded acres were consistent over all course features averaging

a roughly 68% reduction. However, in the Southwest region, reductions in overseeded roughs (69%) and practice areas (68%) were twice that of the greens, tees and fairways, which averaged 33%.

We postulate three primarily explanations for the reduction of winter overseeding. First, winter overseeding is resource intensive, especially with water and nutrients (25, 27). Reductions in winter-overseeded acreage may be attributed to resource conservation

practices, especially in the Southwest region, where water supply constraints are prevalent (25). Second, the use of pigments and dyes used to color dormant warm-season turfgrasses green likely increased from 2005 to 2021, which would replace winter

overseeded area. Last, the cost of seed increased disproportionately from 2005 to 2021 (16). Increased seed cost may be a result of several factors, including supply, inflation, etc.

Table 7. Frequency of golf facilities in the U.S. Upper West/Mountain region that have the listed turfgrass species or cultivar on greens, fairways, tees, roughs or practice areas in 2005, 2015 and 2021.

Conclusions

The total area of maintained turfgrass on U.S. golf facilities declined from 2005 to 2021, which may be a result of both course closures and a reduction of maintained acres at operational golf facilities. Winter-overseeded acreage declined to historic

lows in all regions except the North Central and Pacific regions. The percentage of golf facilities that reported having cool-season turfgrasses varied according to region, with minimal fluctuations in the cooler regions. However, in the warmer regions

of the Transition and Southeast, it appears golf facilities are relying less on cool-season turfgrasses in 2022 compared to 2005. Minor but significant increases in the use of zoysiagrass and seashore paspalum were reported in most regions where both

cool-season and warm-season turfgrasses are commonly grown. Whether in historically cool-season or warm-season regions, it appears that many golf facilities are incorporating alternative species on their landscape and playing surfaces.

The Research Says…

- The total area of maintained turfgrass on U.S. golf facilities declined from 2005 to 2021, which may be a result of course closures and a reduction of maintained acres at operational golf facilities.

- Winter-overseeded acreage declined to historic lows in all regions except the North Central and Pacific regions.

- The percentage of golf facilities that reported having cool-season turfgrasses varied according to region with minimal fluctuations in the cooler regions. However, in the warmer regions of the Transition and Southeast, it appears golf facilities are

relying less on cool-season turfgrasses in 2022 compared to 2005.

- Minor but significant increases in the use of zoysiagrass and seashore paspalum were reported in most regions where both cool-season and warm-season turfgrasses are commonly grown.

Table 8. Projected acres of overseeded turfgrass by course feature for U.S. golf facilities in 2005, 2015 and 2021.

Literature cited

- Bigelow, C.A., and W.T.J. Tudor. 2012. Economic analysis of creeping bentgrass and annual bluegrass greens maintenance. Golf Course Management 80:76-93.

- Braun, R.C., A.J. Patton, A. Chandra, J.D. Fry, A.D. Genovesi, M. Meeks, M.M. Kennelly, et al. 2022. Development of winter hardy, fine-leaf zoysiagrass hybrids for the upper transition zone. Crop Science 62(6):2486-2505 (https://doi.org/10.1002/csc2.20834).

- Brosnan, J.T., J.B. Peake and B.M. Schwartz. 2022. An examination of turfgrass species use on golf course putting greens. Crop, Forage and Turfgrass Management 8:e20160 (https://doi.org/10.1002/cft2.20160).

- Carroll, D.E., B.J. Horvath, M. Prorock, R.N. Trigiano, A. Shekoofa, T.C. Mueller and J.T. Brosnan. 2022. Poa annua: An annual species? Plos One 17:e0274404 (https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0274404).

- Cavanaugh, M., E. Watkins, B. Horgan and M. Meyer. 2011. Conversion of Kentucky bluegrass rough to no-mow, low-input grasses. Applied Turfgrass Science 8(1):1-15 (https://doi.org/10.1094/ATS-2011-0926-02-RS).

- Chandra, A., A.D. Genovesi, M. Meeks, Y. Wu, M.C. Engelke, K. Kenworthy and B. Schwartz. 2020. Registration of ‘DALZ 1308’ zoysiagrass. Journal of Plant Registrations 14(1):19-34 (First published: 19 February 2020 https://doi.org/10.1002/plr2.20016).

- Dernoeden, P.H. 2013. Creeping bentgrass management. CRC Press, Boca Raton, Fla.

- DeBoer, E.J., M.D. Richardson, J.H. McCalla and D.E. Karcher. 2019. Reducing ultradwarf bermudagrass putting green winter injury with covers and wetting agents. Crop, Forage and Turfgrass Management 5(1):1-9 (https://doi.org/10.2134/cftm2019.03.0019).

- Doguet, D., and V.G. Lehman (inventors). 2014 Zoysiagrass plant named ‘L1F’. Doguet, D., Lehman, V., (assignees). U.S. Plant Patent 25,203. (Filed April 16, 2013, granted Dec. 30, 2014).

- Doguet, D., D.A. Doguet and V.G. Lehman (inventors). 2016a Zoysiagrass plant named ‘M60’. D. Doguet, D.A. Doguet, V.G. Lehman (assignees). U.S. Plant Patent 29,143. (Filed May 20, 2016, granted March 20, 2018).

- Doguet, D., D.A. Doguet and V.G. Lehman (inventors). 2016b Zoysiagrass plant named ‘M85’. D. Doguet, D.A. Doguet, V.G. Lehman (assignees). U.S. Plant Patent 27,289. (Filed May 29, 2015, granted Oct. 18, 2016).

- Duncan, R.R., and R.N. Carrow. 2000. Seashore paspalum: the environmental turfgrass. Sleeping Bear Press, Chelsea, Mich.

- Fry, J., and B. Huang. 2004. Applied turfgrass science and physiology. J. Wiley, Hoboken, N.J.

- Gelernter, W.D., L.J. Stowell, M.E. Johnson and C.D. Brown. 2017. Documenting trends in land-use characteristics and environmental stewardship programs on US golf courses. Crop, Forage and Turfgrass Management 3(1):1-12 (https://doi.org/10.2134/cftm2016.10.0066).

- Heap, I. 2023. The international herbicide-resistant weed database. https://www.weedscience.org/Home.aspx (accessed June 28, 2023).

- Isom, C. 2021. Sizing up a seed shortage. https://www.usga.org/content/usga/home-page/course-care/green-section-record/59/07/sizing-up-a-seed-shortage.html. (accessed June 29, 2023).

- Jespersen, D., E. Merewitz, Y.Xu, J. Honig, S. Bonos, W. Meyer and B. Huang. 2016. Quantitative trait loci associated with physiological traits for heat tolerance in creeping bentgrass. Crop Science 56(3):1314-1329 (https://doi.org/10.2135/cropsci2015.07.0428).

- Jespersen, D., X. Ma, S.A. Bonos, F.C. Belanger, P. Raymer and B. Huang. 2018. Association of SSR and candidate gene markers with genetic variations in summer heat and drought performance for creeping bentgrass. Crop Science 58(6):2644-2656 (https://doi.org/10.2135/cropsci2018.05.0299).

- Lyman, G.T., C.S. Throssell, M.E. Johnson, G.A. Stacey and C.D. Brown. 2007. Golf course profile describes turfgrass, landscape, and environmental stewardship features. Applied Turfgrass Science 4(1): 1-25 (https://doi.org/10.1094/ATS-2007-1107-01-RS).

- Meeks, M., S.T. Kong, A.D. Genovesi, B. Smith and A. Chandra. 2022. Low-input golf course putting green performance of fine-textured inter- and intra-specific zoysiagrass (Zoysia spp.). International Turfgrass Society Research Journal 14(1):610-621

(https://doi.org/10.1002/its2.63).

- Merewitz, E., F. Belanger, S. Warnke, B. Huang and S. Bonos. 2014. Quantitative trait loci associated with drought tolerance in creeping bentgrass. Crop Science 54(5):2314-2324 (https://doi.org/10.2135/cropsci2013.12.0810).

- Patton, A.J., B.M. Schwartz and K.E. Kenworthy. 2017. Zoysiagrass (Zoysia spp.) history, utilization, and improvement in the United States: A review. Crop Science 57 (S1):S-37-S-72 (https://doi.org/10.2135/cropsci2017.02.0074).

- Petrella, D.P., S. Bauer, B.P. Horgan and E. Watkins. 2021. Exploring fine fescues as an option for low-input golf greens in the north-central USA. Crop Science 61(5):2949-2962 (https://doi.org/10.1002/csc2.20390).

- Raymer, P.L., S.K. Braman, L.L. Burpee, R.N. Carrow, Z. Chen and T.R. Murphy. 2008. Seashore paspalum: Breeding a turfgrass for the future. USGA Green Section Record 46:22-26.

- Shaddox, T.W., J.B. Unruh, M.E. Johnson, C.D. Brown and G. Stacey. 2022. Water use and management practices on U.S. golf courses. Crop, Forage and Turfgrass Management 2022;8:e20182 (https://doi.org/10.1002/cft2.20182).

- Shaddox, T.W., J.B. Unruh. M.E. Johnson, C.D. Brown and G. Stacey. 2023a. Land-use and energy practices on U.S. golf courses. HortTechnology 33(3):296-304 (https://doi.org/10.21273/HORTTECH05207-23).

- Shaddox, T.W., J.B. Unruh, M.E. Johnson, C.D. Brown and G. Stacey. 2023b. Nutrient use and management practices on U.S. golf courses. HortTechnology 33(1):79-98 (https://doi.org/10.21273/HORTTECH05118-22).

- Unruh, J.B., B.J. Brecke and D.E. Partridge. 2007. Seashore paspalum performance to potable water. USGA Turfgrass and Environmental Research Online 6(23):1-10 (https://usgatero.msu.edu/v06/n23.pdf).

- U.S. Golf Association. 2017. Improving bentgrass heat tolerance (https://www.usga.org/course-care/turfgrass-and-environmental-research/research-updates/2017/improving-bentgrass-heat-tolerance.html) (accessed June 28, 2023).

- Van Wychen, L. 2021. WSSA survey ranks most common and most troublesome weeds in grass crops, pasture and turf. https://wssa.net/2021/05/wssa-survey-ranks-most-common-and-most-troublesome-weeds-in-grass-crops-pasture-and-turf (accessed June 28, 2023).

- Watkins, E., A.B. Hollman and B.P. Horgan. 2010. Evaluation of alternative turfgrass species for low-input golf course fairways. Hortscience 45(1):113-118 (https://doi.org/10.21273/HORTSCI.45.1.113).

J. Bryan Unruh, Ph.D., (jbu@ufl.edu) is a professor and associate center director at the University of Florida, Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences’ West Florida Research and Education Center in Jay, Fla. Travis Shaddox, Ph.D., is president of Bluegrass Art and Science LLC, Lexington, Ky.