Texas A&M AgriLife and the U.S. Department of Agriculture are studying zoysiagrass to determine whether it’s water-efficient and cold hardy in Texas Panhandle landscapes. Photos by Kay Ledbetter

The front lawn of a Texas home built during the Dust Bowl in a location known for soil and water conservation research seems an appropriate place for a turfgrass project aimed at finding a water-smart alternative to bermudagrass and fescue for the High Plains.

The new turfgrass demonstration has been installed in front of the 1938 vintage “white house” in Bushland, Texas, the original headquarters of the Conservation and Production Research Laboratory, which is now jointly operated by the U.S. Department of Agriculture-Agricultural Research Service and Texas A&M AgriLife Research.

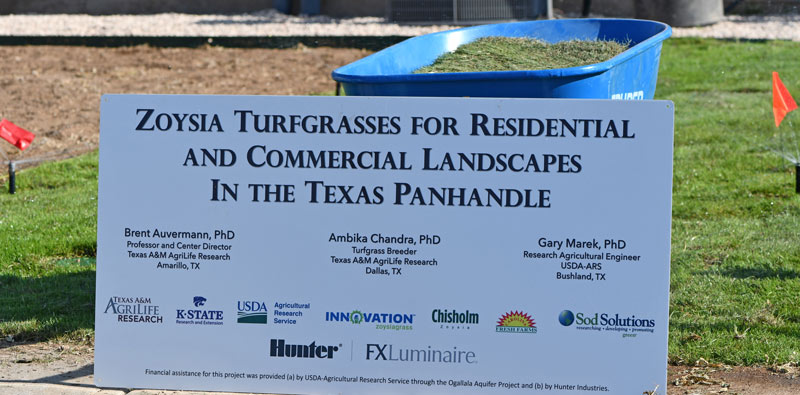

The project, titled “Zoysia Turfgrasses for Residential and Commercial Landscapes in the Texas Panhandle,” is being conducted by Brent Auvermann, Ph.D., AgriLife Research center director, Amarillo, Texas; Ambika Chandra, Ph.D., AgriLife Research turfgrass breeder, Dallas; and Gary Marek, Ph.D., USDA-ARS research agricultural engineer, Bushland, Texas.

The demonstration has a state-of-the-art irrigation system and two zoysiagrass varieties, Chisholm and Innovation, recently released by Chandra and Jack Fry, Ph.D., a turfgrass science professor at Kansas State University.

Take a look at the site of the zoysiagrass demonstration and hear from the researchers:

Compared with other warm-season turfgrasses, zoysiagrass generally produces higher-quality turf that requires fewer inputs such as mowing, nutrients and chemicals thanks to its natural tolerance to disease, insects, shade and salinity stress, Chandra says. Chandra has been breeding freeze-tolerant zoysiagrass varieties as part of an ongoing project with Kansas State since 2003.

“While zoysia’s low-input requirements, strong shade tolerance and salinity tolerance make it an attractive option for use across the U.S., most species are still found in the southern U.S. due to low tolerance for freezing temperatures,” Chandra says.

The Dallas center’s turf breeding program produced 640 zoysia hybrids in 2004 and sent them to Kansas to be evaluated for cold tolerance. The breeding lines that survived the cold were then evaluated for aesthetic quality and a range of other characteristics, Chandra says.

Zoysiagrass sod laid at the Conservation and Production Research Laboratory in Bushland, Texas.

Chisholm, licensed to Carolina Fresh Farm, is a medium-texture zoysiagrass that is cold hardy into the northern region of the U.S. transition zone. It features rapid establishment and recovery rates as well as superior turf quality compared with Meyer zoysia. Chisholm underwent testing in the National Turfgrass Evaluation Program’s 2002 National Zoysiagrass Test as DALZ 0102.

Innovation, originally KSUZ 0802 and licensed to Sod Solutions, features finer leaf texture and superior density compared with Meyer, Chandra says. It’s a good option for landscapers and end users in the transition zone and beyond who are looking for a cold-hardy hybrid for golf courses, yards, parks or commercial establishments.

“I expect both of these varieties to not only survive the Texas Panhandle climate, but to produce good turfgrass quality with limited resource input,” Chandra says.

Auvermann says that half the sod in the Bushland side-by-side variety comparisons was laid on existing soil, and the other half on existing soil amended with composted cattle manure to test what role fertility and organic matter have in its survivability.

“We think the zoysiagrass will provide an alternative for landscape contractors for both residential and commercial markets,” Auvermann says. “Zoysiagrasses act a little bit like bermudagrass in that they creep and repair themselves. They also use less water than the fescues typically used for the landscaping projects in the Texas Panhandle.”

Zoysiagrass bred by Texas A&M AgriLife Research turfgrass breeder Ambika Chandra, Ph.D., in Dallas.

Marek says developing irrigation scheduling strategies for seasonal crops is one of the primary research goals of the USDA-ARS program at Bushland. Prudent irrigation scheduling provides enough water to achieve desired yield goals but prevents overwatering that results in water percolating below the root zone.

“Those same concepts can be applied to turf irrigation,” Marek says.

Traditionally, according to Marek, three grass varieties have been available to homeowners for turfgrass: fescue, bermudagrass and buffalograss, with fescue using the most water out of the three. Fescue greens up earlier and stays green longer than other varieties, so aesthetically, it’s generally more pleasing. “However, fescue can use up to a half-inch of water per day on hot, windy days typical of the Panhandle summers,” he says.

“One of the benefits we hope to evaluate in this trial is to see if these zoysia varieties can compare to fescue grass in aesthetics while using less water,” Marek says.

In addition to water use, the other focus of the project is to determine how well the zoysiagrass overwinters in the colder climate of the Panhandle.

“If these two varieties prove adapted to our climate, as we expect, they ought to use significantly less water than our typical tall fescues, heal themselves, withstand the winters, and maintain a luxurious, fine-bladed turf,” Auvermann says.

The project is funded in part by the federal Ogallala Aquifer Project.