Golf course superintendents reported an increase in their reliance upon fungicides, herbicides and insecticides from 2015 to 2021, but more reported having either

an integrated pest management plan or a pesticide application plan. Photo courtesy of PBI-Gordon

Integrated pest management (IPM) is a foundational component of golf course maintenance best management practices (BMPs) and combines five key principles:

- Identifying key pests, their hosts and beneficial organisms prior to acting;

- Establishing robust monitoring programs for known pests;

- Establishing tolerance thresholds for the various pests;

- Evaluating and implementing control measures; and

- Monitoring, evaluating and documenting the results leading to continued improvement and reduced resource utilization. Control measures include nonchemical cultural management practices aimed at reducing stress to the turf and conventional chemical

pesticide use.

Documenting the golf course management industry use of pest management practices is critical to the development, teaching and adoption of BMPs. As such, GCSAA has been benchmarking the management practices, property features and environmental stewardship

of U.S. golf courses since 2005. This endeavor, referred to as the Golf Course Environmental Profile (GCEP) Survey Series, is now in its third iteration, and results from these surveys are routinely used by those interested in golf course management.

Pest management practices on U.S. golf facilities were previously documented in 2007 (7) and 2015 (4) in prior GCEP surveys. In their continued commitment to servicing the golf course industry, GCSAA conducted a third survey in 2021. The objective of

the 2021 survey was to compare results from 2007 to determine where changes have occurred in the following areas:

- Reliance on pest management practices.

- Frequency of pesticide storage and pesticide mixing and loading attributes.

- Reliance on pesticides.

In this article, we summarize the results from the 2021 survey on pest management practices on U.S. golf courses and determine if changes have occurred since 2007 (11).

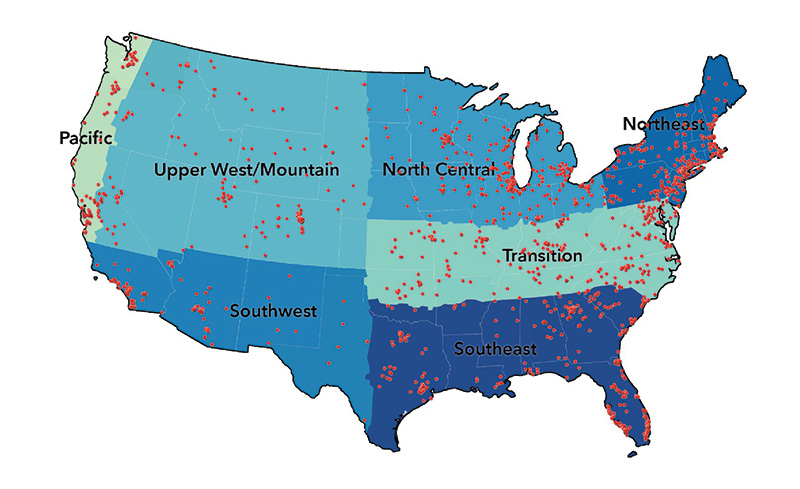

Figure 1. Geographic distribution of respondents to GCSAA’s surveys and the designated agronomic regions.

Methodology

To compare changes from prior surveys, questions were identical to those used in 2006 and 2014. A survey link was emailed to golf facilities using the mailing lists of the National Golf Foundation and GCSAA, which resulted in the link being sent to 14,033

unique golf facilities. A golf facility was defined as a business where golf could be played on one or more golf courses. The survey and the link were also promoted on social media by GCSAA staff. The survey was available for completion for seven

consecutive weeks beginning on April 1, 2022. Respondents remained anonymous within the data file by omitting their names and assigning a unique identification number. Data were merged with data from the same survey conducted in 2006 and 2014 to allow

for a measurement of change over time. Responses were received from 1,444 facilities, which represented 10.3% of the known total of U.S. golf facilities.

Respondents were grouped by agronomic region (Figure 1). To provide a valid representation of U.S. golf courses, data were weighted. Responses were categorized into one of 35 categories depending upon the facility type (public or private), number of holes

(9, 18 or 27 plus), and public green fee (< $55 or ≥ $55 per round). The weights were calculated by determining the proportion of each group within the total survey response. Golf facility frequencies were calculated using statistical software.

Differences among years were determined using the χ2 test at the 10% significance level.

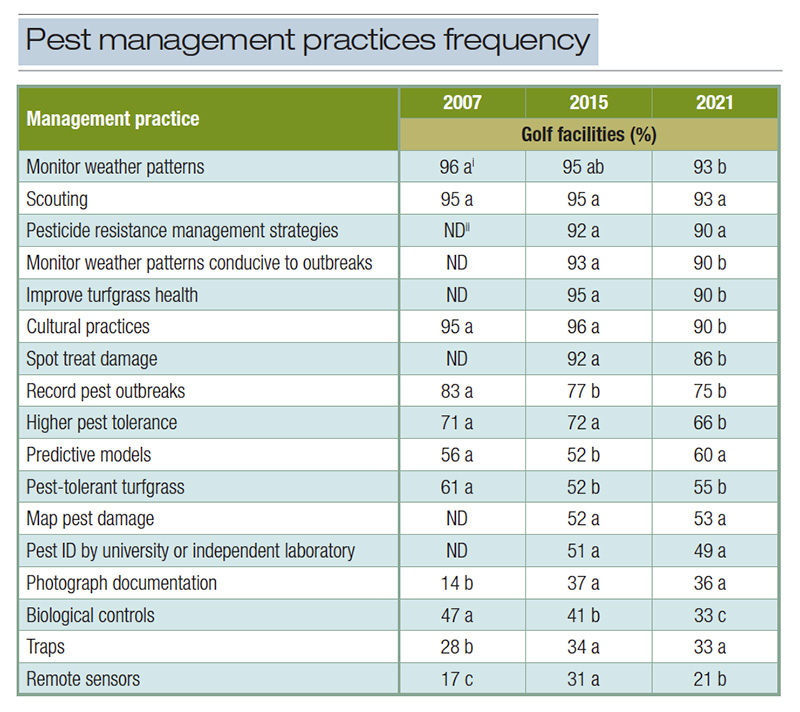

Table 1. Frequency of pest management practices used on U.S. golf facilities in 2007, 2015 and 2021. i Within rows, values followed by a common letter are not significantly different according to the χ2 test at the 10% significance level. ii No data. Question was not asked in 2007.

Results and discussion

Pest management practices

Golf course superintendents employ various management practices aimed at reducing the impact of pests on their golf courses. Of the 17 practices included in the survey instrument, the use of seven practices declined, nine practices remained the same,

and one practice increased from 2015 to 2021 (Table 1). Scouting for pests and monitoring weather patterns, major tenets of IPM, were the most common management practices and were used by 93% of golf facilities in the U.S.

Those management practices that were reported to be used less frequently include monitoring weather patterns conducive to outbreaks, improving turfgrass health, implementing cultural practices and spot-treating damage. Regardless, these practices are

still employed by approximately 90% of golf facilities, suggesting that their importance has not diminished. The use of remote sensing nearly doubled between the inaugural survey in 2007 and 2015 but has since declined to one in five golf facilities

reporting its use. A limitation to remote sensing is the correlation of the remote sensing data with turfgrass performance. This is a common research area, and we postulate that remote sensing data will become more useful to the golf course superintendent

in time, which may lead to increased use of remote sensing technology in the future.

The one management practice that saw increased use was the use of predictive models to better time pesticide applications. Current research has confirmed that modeling turfgrass growth can result in more efficient use of resources (6, 8). Similarly, weather-based

disease warning systems using predictive models have been developed to accurately time fungicide applications (12).

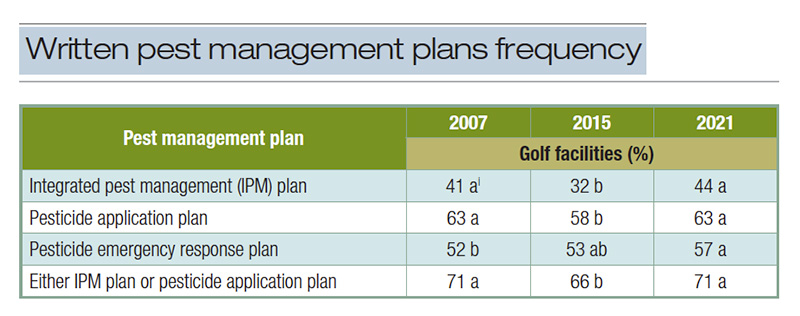

Table 2. Frequency of written pest management plans on U.S. golf facilities in 2007, 2015 and 2021. i Within rows, values followed by a common letter are not significantly different according to the χ2 test at the 10% significance level.

Pest management plans

As noted, a major tenet of IPM is monitoring, evaluating and documenting the results of a plan. In 2021, superintendents at 71% of U.S. golf facilities reported having either an IPM plan or a pesticide application plan — up from 66% in 2015 but

equivalent to 2007 (Table 2). The data suggests that preference is being given to IPM plans (12% increase since 2015) versus a pesticide application plan (5% increase since 2015). An IPM plan is a much broader approach to managing pests than the singular

focus of pesticide applications. The percentage of facilities reporting to have a pesticide emergency response plan is static and remains at 57%.

When golf facilities have annual budgets exceeding $1 million, the frequency of having written IPM plans, pesticide emergency response plans, and either an IPM or pesticide application plan increases compared to golf facilities with annual budgets less

than $1 million (data not presented). These facilities typically have the labor and fiscal resources to devote to pest management planning.

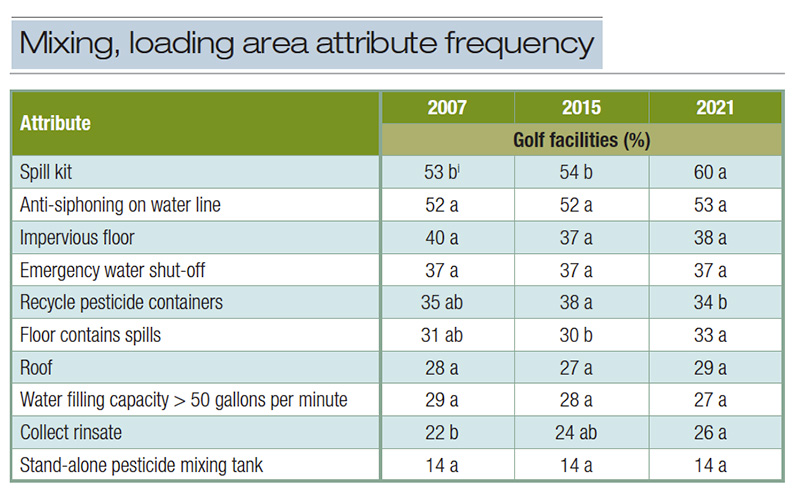

Table 3. Frequency of mixing and loading area attributes on U.S. golf facilities in 2007, 2015 and 2021. i Within rows, values followed by a common letter are not significantly different according to the χ2 test at the 10% significance level.

Pesticide mixing, loading and storage areas

Areas for storing, mixing and loading pesticides present increased opportunities for mishaps to occur. Consequently, golf course superintendents employ pollution-prevention practices in and around these areas, and the GCEP survey measured the degree to

which these practices are being employed.

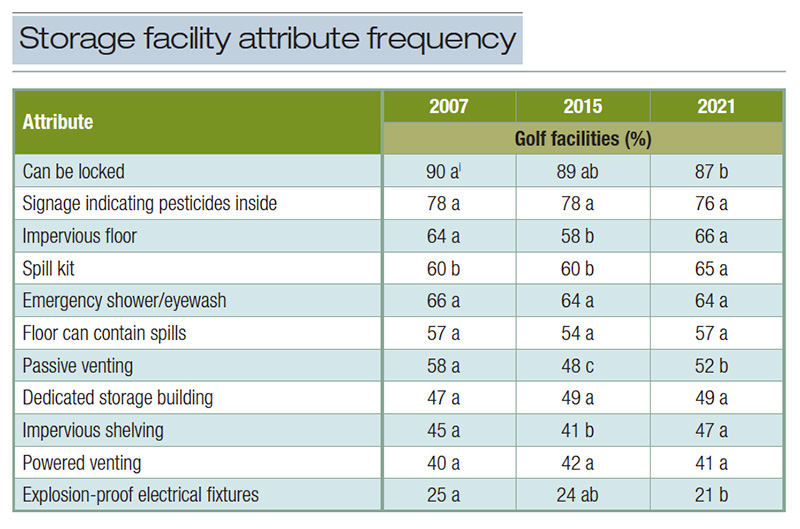

Of the 11 attributes of pesticide storage facilities, the use of seven were equivalent to what was reported in 2007 (Table 3). The frequency of the storage facility being locked declined from 90% to 87% from 2007 to 2021 but did not change from 2015 to

2021. Passive venting declined from 58% to 52% from 2007 to 2021, but the frequency increased from 2015 to 2021. Finally, explosion-proof electrical fixtures declined from 25% to 21% from 2007 to 2021.

Respondents reported 65% of golf facilities had spill kits in the storage facility in 2021, an increase from 2007 and 2015. The inclusion of spill kits is a relatively minor expense that can have a significant impact on reducing environmental risk should

an accident occur. The use of signage to designate that pesticides were stored inside the facility has remained static (71% of facilities) and should be addressed by those facilities not having signage.

Golf course superintendents reported that the attributes of the pesticide mixing and loading areas on their facilities in 2021 remained equivalent to those from 2015 with two exceptions — the presence of spill kits and spill containment flooring

(Table 4). In 2021, the presence of spill kits in these areas increased from 54% to 60%. The presence of floors that contain any spills increased from 30% to 33% between 2015 to 2021.

Compared to the baseline survey of 2007, only two pesticide mixing and loading area attributes increased in 2021 — the presence of spill kits and the collection of rinsate. As noted, the use of spill kits and rinsate collection are critical components

of golf course best management practices, since both reduce the risk of environmental impairment by reducing the risk of unwanted chemicals from entering the environment.

Intuitively, those golf facilities with annual operating budgets greater than $1 million compared to facilities with annual operating budgets less than $500,000 had a greater percentage of each attribute of both pesticide storage and pesticide mixing

and loading areas (data not presented). Capital investments in pesticide storage facilities and mixing and loading stations can be cost-prohibitive. However, modest investments in existing facilities can be made, including floor sealing and the installation

of anti-siphoning and emergency shut-off devices. The costs associated with improvements in pesticide-related facilities should be measured against potential worker and environmental risk.

Table 4. Frequency of storage facility attributes on U.S. golf facilities in 2007, 2015 and 2021. i Within rows, values followed by a common letter are not significantly different according to the χ2 test at the 10% significance level.

Reliance on pesticides

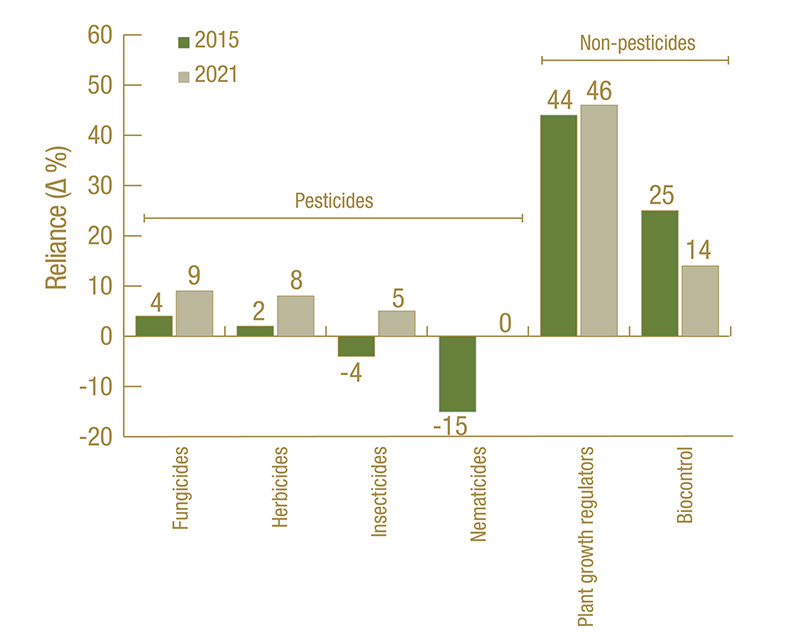

Golf course superintendents reported an increase in their reliance upon fungicides (9%), herbicides (8%) and insecticides (5%) from 2015 to 2021 (Figure 2). The greatest increase in pesticide reliance in the three years prior to each survey occurred with

nematicides. Prior to the baseline survey in 2007, fenamiphos (Nemacur) was considered the industry standard for the treatment of nematodes in turfgrass (3). However, the sale and distribution of fenamiphos was prohibited in the turf and ornamental

market in 2008, and existing stocks of fenamiphos were prohibited from use in 2014 (5). These restrictions likely resulted in a decrease in reliance on nematicides by 15% in 2015. Since that time, however, new active ingredients including abamectin

(Divanem, Syngenta), fluensulfone (Nimitz Pro G, Quali-Pro) and fluopyram (Indemnify, Bayer/Envu) have been documented to control nematodes and result in increased turfgrass quality (1, 2). Therefore, the increased reliance on nematicides measured

from 2015 to 2021 is likely a result of the influx of new nematicides in the turfgrass market.

Reliance upon plant growth regulators (PGRs) has remained consistent, with approximately 45% of facilities indicating that PGRs are used. As previously mentioned, the use of predictive models to better time pesticide applications (e.g., PGRs) has increased

over time. However, the predictive models do not appear to be increasing the reliance on this class of chemistry.

Interestingly, the reliance upon biocontrol products such as polyoxin D, phosphites and corn gluten meal declined from 25% to 14% between 2015 and 2021. In general, the efficacy of biocontrol products is lower than that of conventional pesticides. As

such, biocontrol products are often used to augment conventional pest control products, which may reflect the reduced reliance (i.e., the superintendent doesn’t necessarily “rely” on the biocontrol product for control; the expectation

may be to reduce populations, etc.).

Figure 2. Golf course superintendents reported an increase in their reliance upon fungicides (9%), herbicides (8%) and insecticides (5%) from 2015 to 2021. Reliance upon plant growth regulators (PGRs) has remained consistent with ~45% of facilities indicating that PGRs are used. Reliance upon biocontrol products such as polyoxin D, phosphites and corn gluten meal declined from 25% to 14% between 2015 and 2021.

Conclusions and recommendations

The percentage of golf facilities that engage in the pest management options listed in the survey remains high, with more than 50% of facilities reporting that they employ 13 of the 17 practices. However, the percentage of golf facilities using many of

these practices has declined over time. The reasons for these changes are not known. Increasing awareness via educational endeavors may encourage golf facilities to reconsider the financial and environmental value of these management practices.

The percentage of facilities that use written pest management plans generally remained unchanged from 2007 to 2021, suggesting that improvements in this area are needed. Written plans are key to producing high-quality playing surfaces and protecting the

environment. Written plans lead to more effective decision-making, improved site-specific planning and improved communication. GCSAA has produced many useful tools to assist in developing written IPM plans (https://www.gcsaa.org/environment/environmental-by-topic/ipm-resources).

The COVID-19 pandemic had negligible influence on pesticide usage in 2021 (data not presented). This differs somewhat from nutrient usage during the pandemic, when slightly over one-half of the facilities that reported an increase in applied nutrients

attributed the increase to more rounds being played (10). Similarly, golf course superintendents reported a 19% increase in water usage during the pandemic although the factors contributing to these changes are not clearly defined (9).

Funding

The Golf Course Environmental Profile has been funded in part by the USGA through the GCSAA Foundation.

Additional Information

All GCEP surveys are published in peer-reviewed scientific journals including Crop, Forage and Turfgrass Management (previously Applied Turfgrass Science) (https://access. onlinelibrary.wiley.com/journal/23743832) and HortTechnology (https://journals.ashs.org/horttech/view/journals/horttech/horttech-overview.xml).

Abbreviated results are published in Golf Course Management magazine (https://gcmonline.com), and full reports including all the data are available online (https://www.gcsaa.org/Environment/golf-course-environmental-profile).

The research says

- The one management practice that saw increased use was the use of predictive models to better time pesticide applications. Current research has confirmed that modeling turfgrass growth can result in more efficient use of resources.

- The data suggests that preference is being given to integrated pest management plans (12% increase since 2015) versus a pesticide application plan (5% increase since 2015). An IPM plan is a much broader approach to managing pests than the singular

ocus of pesticide applications.

- Compared to the baseline survey of 2007, only two pesticide mixing and loading area attributes increased in 2021 — the presence of spill kits and the collection of rinsate.

- Golf course superintendents reported an increase in their reliance upon fungicides (9%), herbicides (8%) and insecticides (5%) from 2015 to 2021. The greatest increase in pesticide reliance in the three years prior to each survey occurred with nematicides.

Literature cited

- Crow, W.T. 2017. New golf course nematicides. Golf Course Management. https://www.gcsaa.org/gcm/2017/july/new-golf-course-nematicides [accessed Jan. 12, 2023].

- Crow, W.T. 2020. Nematode management for golf courses in Florida. https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/pdf/IN/IN12400.pdf [accessed Jan. 12, 2023].

- Crow, W.T., D.W. Lickfeldt and J.B. Unruh. 2005. Management of sting nematode (Belonolaimus longicaudatus) on bermudagrass putting greens with 1,3-dichloropropene. International Turfgrass Society Research Journal. 10:734-741.

- Gelernter, W.D., L.J. Stowell, M.E. Johnson and C.D. Brown. 2016. Documenting trends in pest management practices on U.S. golf courses. Applied Turfgrass Science 2(1):1-9 (https://doi.org/10.2134/cftm2016.04.0032).

- Keigwin, R.P. 2011. Fenamiphos; amendment to use deletion and product cancellation order. Federal Register 76:61690-61692.

- Kreuser, W.C., J.R. Young and M.D. Richardson. 2017. Modeling performance of plant growth regulators. Agricultural and Environmental Letters 2(1):1-4 (https://doi.org/10.2134/ael2017.01.0001).

- Lyman, G.T., M.E. Johnson, G.A. Stacey and C.D. Brown. 2012. Golf course environmental profile measures pesticide use practices and trends. Applied Turfgrass Science 9(1):1-19 (https://doi.org/10.1094/ATS-2012-1220-01-RV).

- Reasor, E.H., J.T. Brosnan, J.P. Kerns, W.J. Hutchens, D.R. Taylor, J.D. McCurdy, D.J. Soldat and W.C. Kreuser. 2018. Growing degree day models for plant growth regulator applications on ultradwarf hybrid bermudagrass putting greens. Crop Science

58(4):1801-1807 (https://doi.org/10.2135/cropsci2018.01.0077).

- Shaddox, T.W., J.B. Unruh, M.E. Johnson, C.D. Brown and G. Stacey. 2022. Water use and management practices on U.S. golf courses. Crop, Forage and Turfgrass Management 8(2):e20182 (https://doi.org/10.1002/cft2.20182).

- Shaddox, T.W., J.B. Unruh, M.E. Johnson, C.D. Brown and G. Stacey. 2023. Nutrient use and management practices on United States golf courses. HortTechnology 33(1):1-20 (https://doi.org/10.21273/HORTTECH05118-22).

- Shaddox, T.W., J.B. Unruh, M.E. Johnson, C.D. Brown and G. Stacey. 2023. Pest management practices on United States golf courses. HortTechnology 33(2):1-11 (https://doi.org/10.21273/HORTTECH05117-22).

- Smith, D.L., J.P. Kerns, N.R. Walker, A.F. Payne, B. Horvath, J.C. Inguagiato, J.E. Kaminski, M. Tomaso-Peterson and P.L. Koch. 2018. Development and validation of a weather-based warning system to advise fungicide applications to control dollar spot

on turfgrass. PLOS One (https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0194216).

J. Bryan Unruh, Ph.D., (jbu@ufl.edu) is a professor and associate center director at the University of Florida, Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences’ West Florida Research and Education Center in Jay, Fla. Travis Shaddox, Ph.D., is president of Bluegrass Art and Science LLC, Lexington, Ky.