Figure 1. The first U.S. putting green treated with PoaCure was hole No. 7 at Spotswood Country Club in Harrisonburg, Va. — where Kip Fitzgerald is the GCSAA Class A superintendent — on March 17, 2009. This trial on hole No. 8 was initiated one year later and still had visible plot effects five years after study completion. Photos by Shawn Askew

Annual bluegrass has been the most troublesome weed of golf turf for longer than you might think. In a 1921 USGA Green Section article by Piper and Oakley, it was noted that the weed was “practically everywhere” in the United States, and the scientific name, Poa annua, was used as often as the common name. They also noted that “once established it volunteers year after year, increasing in abundance.”

Not much has changed in the past 100 years. If anything, control of annual bluegrass on golf course greens has become more challenging in the past four decades because of the loss of mercury-based fungicides and demands for lower mowing heights.

What’s the problem with Poa annua?

Annual bluegrass makes greens management more difficult and can negatively impact the golfer’s experience by reducing aesthetic uniformity and altering playability. My student Sandeep Rana and I recently published a pair of articles in Crop Science (7, 8) on how annual bluegrass affects ball roll direction of golf putts. After controlling for several sources of error and using a putt robot, the study showed that imprecision of ball direction caused by a pure creeping bentgrass (Agrostis palustris) green canopy extrapolates to consistent “hole out” for putts up to 21 feet (6.4 meters). When the ball encounters an isolated patch of annual bluegrass, that distance is reduced to 9 feet (2.7 meters).

Annual bluegrass is an opportunistic invader that rapidly fills turf voids caused by turf loss during biotic and abiotic stress. Once established, it becomes an integral part of the greens canopy, albeit with different color and texture.

The problem is that annual bluegrass apparently spent all of its evolutionary credit on invasion and adaptation and very little on long-term survival. Once the plants reach reproductive maturity, they can be rapidly killed by diseases, pests or extreme weather. Some pests, such as the annual bluegrass weevil, anthracnose, rapid blight fungi and stem gall nematode, are magnified by annual bluegrass presence. Thus, large annual bluegrass populations can substantially alter budget allocation for plant-protection products, irrigation and heat management that may not have otherwise been needed.

PoaCure: A new product for Poa annua control

So, annual bluegrass has been a problem for a long time, and it negatively impacts golfer experience and maintenance budgets. Why can’t we just control it?

Iowa State professor Nick Christians, Ph.D., summarized the struggle for selective herbicide options regarding annual bluegrass in a 2006 Grounds Management article:

“Will there ever be a single herbicide that will finally solve the Poa annua problem? It is my opinion that this is very unlikely. The perfect herbicide would have to provide selective pre-emergence and post-emergence control of the many biotypes of Poa annua and be safe for use on a variety of competing species. It is very unlikely that such a material will ever be found.”

The tide may be turning in the struggle against annual bluegrass control on golf courses with the advent of PoaCure (methiozolin). PoaCure SC received U.S. federal registration in December 2019 after an almost 10-year effort by Moghu Research Center, a small company in South Korea led by Suk-Jin Koo, Ph.D. The lengthy registration time was partly due to budget-associated limitations in data quantity and delivery speed and lack of other registered crops (turf only). However, waiting for concurrent registration by California and the U.S. EPA — a gesture of appreciation to California superintendents by the company’s CEO — also contributed to the delay. Another significant pause in the process occurred when the U.S. EPA requested new honey bee data requirements. That alone added years to the registration time.

PoaCure was first sprayed on U.S. putting greens at Spotswood Country Club in Harrisonburg, Va., in spring 2009 (1) (Figure 1, top). The product was registered in South Korea in early 2010 as “PoaBaksa,” which roughly translates to “Poa Doctor.” In June 2016, Japan became the first nation to register methiozolin under the trade name PoaCure. Additional registrations in Australia and South Africa are pending, as are several state registrations in the U.S. It is expected that most U.S. states will have PoaCure registered by summer 2020 and some as early as spring. The product will be available in a soluble concentrate formulation and can be used on all areas of golf courses. Other, non-golf sites may be added later.

The proof is in the pudding

If ever there were a herbicide that matched the requirements outlined by Christians, PoaCure may be it. Greenhouse and laboratory trials have shown that PoaCure can provide pre-emergent control of annual bluegrass at concentrations as low as 0.7 ounce methiozolin per acre (0.05 liter/hectare). That’s comparable to one-tenth the lowest recommended rate for sequential treatments that are used in a post-emergence control program on greens (0.6 fluid ounce/1,000 square feet; 1.9 liters/hectare).

So, we have a herbicide in PoaCure that can kill all known annual bluegrass biotypes post-emergence, as shown in work done at Penn State by Kyung Han and John Kaminski, Ph.D., and at the University of Tennessee (2). The product also provides enough residual activity that it can undergo at least five “half-life” degradation cycles and still control pre-emergent annual bluegrass.

The margin of safety between creeping bentgrass and annual bluegrass is one of PoaCure’s most powerful attributes (Figure 2, below). It is also safe to use on all common turfgrasses except roughstalk bluegrass and annual bluegrass, based on work done by myself; Harold Walker, Ph.D., and Scott McElroy, Ph.D., at Auburn University; Jim Baird, Ph.D., at the University of California, Riverside; Jim Brosnan, Ph.D., at the University of Tennessee; and many others (3, 4, 5, 8).

Figure 2. Creeping bentgrass (top) and annual bluegrass (bottom) following 2½ months of root exposure to approximately 10 parts per billion methiozolin (active ingredient in PoaCure) in an aeroponics system at Virginia Tech. In the aeroponics system, roots were sprayed with routinely herbicide-tainted nutrient solution so that plant stress was minimal. It is easy to see how a lack of roots in annual bluegrass makes plants more susceptible to stress. Differential root exposure in the field along with selective response between species likely govern our ability to safely control annual bluegrass in desirable turf.

Thus, PoaCure meets Christians’ requirements well and also offers the ability to remove annual bluegrass slowly so as to minimize disruption of play. Implementing PoaCure successfully requires one to know the level of annual bluegrass infestation and the predominant phenotype (annual vs. perennial), the prevalent environmental conditions, and pertinent maintenance practices. Key considerations reside around speed of control, mitigating turf safety issues, and turf recovery while preventing reinfestation and herbicide resistance.

Speed limit enforcement

The speed of annual bluegrass removal is generally the only challenge turf managers will have in implementing PoaCure. I’ll talk about some exceptions to turf safety in a moment, but first, let me discuss the two most common mistakes/problems associated with using PoaCure, as they relate to speed of annual bluegrass control.

1. “We stopped spraying because we weren’t seeing anything.”

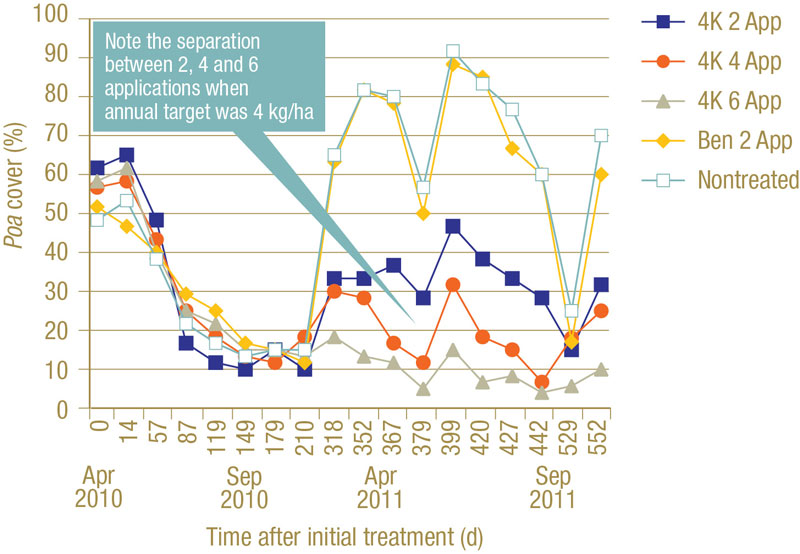

PoaCure has the safety margin in most cases to remove annual bluegrass quickly without harming creeping bentgrass greens, but we don’t recommend aggressive programs on greens for good reason. Treatment programs found on the label are designed to remove annual bluegrass slowly, and the speed of activity will vary with annual bluegrass biotype, time of year, weather conditions and turf maintenance practices. It usually takes two treatments before any symptoms will appear, but it sometimes takes three or even four. Spring programs are designed to reduce annual bluegrass expansion or slightly reduce population levels in preparation for more aggressive fall treatments. Fall treatments are when most of the annual bluegrass dies. Superintendents often mutually agree that they want a slow transition back to desired turf but get discouraged when it appears nothing is happening. It is important to stay on the program, as application frequency in conjunction with environmental stress is necessary to achieve control over time (Figure 3, below).

Figure 3. Annual bluegrass cover over time following two years of treatments totaling 4.8 fluid ounces PoaCure/1,000 square feet/year as influenced by the number of treatments per year and compared with bensulide (Bensumec, PBI-Gordon) applied twice per year per label instruction.

2. “WTH, the Poa is all dying, and we have a member-guest coming up!”

Programs recommended on the label are designed to prevent things like this statement from happening. The following issues often lead to more rapid annual bluegrass decline:

- Increasing rate or frequency because of perceived “slow activity.”

- Calibration errors or spray mistakes that increase rate.

- Too many treatments in fall/winter.

- Heavy or prolonged rainfall after PoaCure application.

- Injurious mechanical treatments (for example, aeration) while on a PoaCure program.

- Disease or pest outbreak blamed on or exacerbated by PoaCure.

- Use of ethephon with PoaCure followed by mild to moderate stress.

- Extreme environmental stress during a PoaCure program.

- Use in conjunction with other herbicides/plant growth regulators (PGRs) that harm annual bluegrass.

Won’t hurt the turf, huh? Hold my beer.

Excessive turf loss

In my 20 years of research experience, PoaCure has the best safety margin of any herbicide or PGR that can selectively control annual bluegrass. As with any herbicide, PoaCure is not bulletproof. In hundreds of demonstrations, PoaCure has transitioned annual bluegrass-infested areas to pure creeping bentgrass, but many of these trials included frightening losses of turf in areas where annual bluegrass infestation was high.

This turf loss is often blamed on damage to desirable creeping bentgrass, but it is usually attributed to loss of higher-than-expected levels of annual bluegrass. Under ideal conditions, creeping bentgrass stand loss requires application in excess of eight times the recommended rate of 0.6 fluid ounce per 1,000 square feet. Add aeration stress within two weeks of PoaCure treatment, and that threshold for stand loss goes down to about six times the recommended rate.

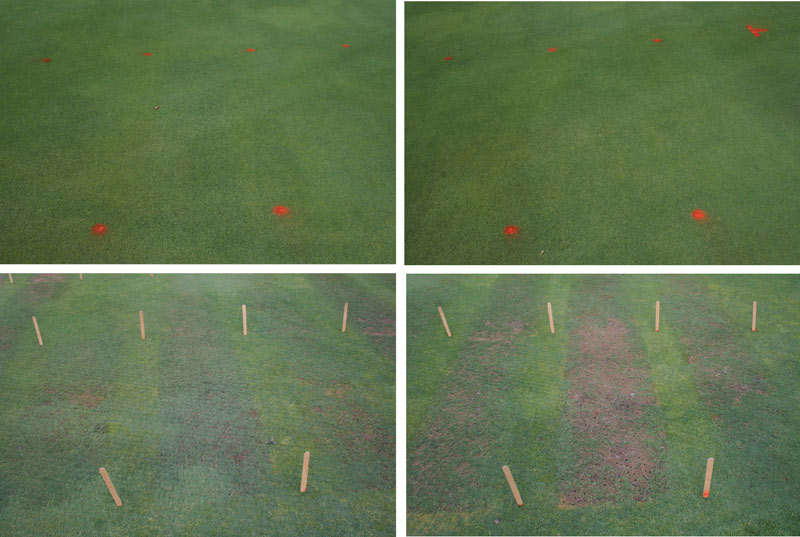

Figure 4. Plots from a Virginia Tech trial showing effects of PoaCure at four times the normal rate of 0.6 fluid ounce/1,000 square feet on turf quality of approximately 50/50 creeping bentgrass/Poa greens eight to nine weeks after treatment as influenced by aeration within two days of treatment and ethephon (Proxy, Bayer) tank mixture. Notice rapid annual bluegrass control with aeration (bottom left) and both annual bluegrass control and creeping bentgrass injury with aeration and Proxy (bottom right), compared with slower annual bluegrass control and no creeping bentgrass injury without aeration (top left = no Proxy; top right = with Proxy).

Add ethephon (Proxy, Bayer) and aeration stress, and it is possible to get creeping bentgrass stand loss at four times the recommended rate (Figure 4, above). We have also seen reduction in creeping bentgrass root density in situations where routine mechanical injury (weekly needle-tine, cleanup laps from riding mowers, etc.) is done in conjunction with heat stress and PoaCure programs.

The most likely culprit is stress-mediated root senescence. On greens not treated with PoaCure, turf will lose a percentage of roots following each stressful event and then replenish those roots rapidly over the next week. These new roots generate from the crown, and a small percentage of them will be exposed to PoaCure and inhibited. So, repeated needle-tine without PoaCure equals root loss and rapid root regeneration, but adding PoaCure reduces the number of roots that regenerate. The solution is to discontinue mechanically stressful practices until after you have finished the PoaCure program and achieved pure creeping bentgrass.

Creeping bentgrass segregation

Figure 5. An image taken of a golf green near Harrisonburg, Va., showing (A) annual bluegrass, (B) a “cold-sensitive” biotype of creeping bentgrass, and (C) less-sensitive creeping bentgrass. These segregated bentgrass types can sometimes respond differently to PoaCure when cold weather is prevalent.

Creeping bentgrass segregation is another issue that often leads to performance confusion when PoaCure is used in late fall or leading into winter. Creeping bentgrass will commonly segregate on greens such that circular patches will be apparent and vary widely in response to cold weather and herbicides like PoaCure (Figure 5, above). We have also seen yellow discoloration to creeping bentgrass associated with multiday canopy saturation or intermittent frost during treatment. These discoloration events are transient and don’t lead to turf thinning in most cases. All of these interacting factors that contribute to creeping bentgrass injury will be magnified under shaded turf conditions. Be extra cautious when using any herbicide on shaded greens or tees.

“I’ll be back” — P. annua

It takes one to two seasons of as many as six PoaCure treatments per year to renovate a golf green infested with annual bluegrass. This endeavor will cost about $5,000 to $10,000 per golf course per year. The first good news is that greens reconstruction, regrassing, etc., cost way more than PoaCure. The other good news is that the maintenance program for PoaCure is a fraction of the renovation program in product use and cost.

Resistance

After the annual bluegrass has been controlled, most courses will need only one spring and one fall treatment to keep the annual bluegrass from returning. That will cost less than a normal PGR program for most courses. Escaped annual bluegrass can be targeted with a dabber or hand-cut. It will be important to aggressively target any escaped plants to prevent possible resistance. In the 10 years that PoaCure has been used overseas, no cases of resistance have yet been reported. Variable response among annual bluegrass biotypes and among greens on the same course have been reported, prompting many to be concerned about resistance development.

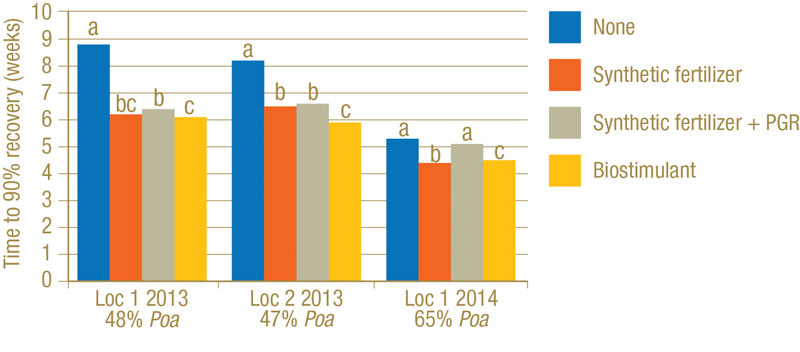

Other treatment programs, such as paclobutrazol or flurprimidol, are another way to combat resistance. These PGRs, however, should not be treated in conjunction with PoaCure, to prevent possible interactions. Work at Virginia Tech showed no differences in annual bluegrass control or creeping bentgrass response from tank mixtures of PoaCure with trinexapac-ethyl, but several golf courses that established PoaCure demonstration plots on turf under treatment with Class B PGRs such as paclobutrazol (Trimmit, Syngenta; Tide Paclo, Sipcam Agro; etc.) and flurprimidol (Cutless, SePRO) have shown decreased annual bluegrass control compared with turf treated with PoaCure alone (K. Han, personal communication). We also observed little negative impact on recovery of voids caused by annual bluegrass control when trinexapac-ethyl (Primo Maxx, Syngenta; T-Nex, Quali-Pro; etc.) was routinely used (Figure 6, below). While holding N-P-K constant at 0.15 pound/1,000 square feet (7.3 kilograms/hectare) every two weeks, Floratine biostimulants improved creeping bentgrass recovery of voided turf slightly compared with conventional fertilizer (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Time required to reach 90% recovery from first canopy loss after rapid annual bluegrass control on highly infested annual bluegrass/creeping bentgrass greens treated with an aggressive PoaCure program as influenced by synthetic fertilizer alone or with a PGR compared with a biostimulant program.

In a separate study, continued spraying of PoaCure during creeping bentgrass recovery following an extreme, 30% removal aeration event delayed creeping bentgrass recovery by 2½ weeks in one of two studies (data not shown). The study in question had an irrigation issue that caused severe drought to occur during the recovery period. When normal moisture status was maintained, PoaCure did not reduce creeping bentgrass recovery time following extreme aeration.

Signal words

PoaCure has been well studied in the U.S. by 30 universities and at over 200 U.S. golf courses. Many additional studies were submitted to the EPA to ensure product safety. Despite the lengthy review, the EPA actually gave PoaCure SC an “unconditional registration.” That’s an uncommon designation for turf herbicides. For example, PoaCure SC will not require a signal word, such as “caution” or “warning,” often found on other pesticide products. An additional formulation, also approved by the EPA, is PoaCure EC, which will have the signal word “danger” on the label because of concerns about some of the surfactants in the blend. The EC product might be marketed along with the SC formulation, depending on client needs in the U.S. There will also be few, if any, restrictions on golf course site uses such as greens. The absence of warnings and restrictions to the products’ use pattern indicate, in part, that the EPA did not find much of a concern from a toxicological or environmental risk standpoint.

No drain tile restrictions

For the over 160 golf course superintendents who participated in the PoaCure Experimental Use Permit, the “drain tile issue” was a transient issue related to speed of workflow with the EPA’s Office of Pesticide Programs. Drain tile restrictions were not advanced to the PoaCure label. The label warns against directly treating bodies of water (a default warning on most pesticides), but it does not even include a setback distance for spraying near bodies of water. Even island greens can be treated as long as the product is not known to be directly exposed to bodies of water. Having testified to the EPA three times over the past decade, I can attest that the agency’s methods are thorough, although sometimes unpredictable and painfully slow. The EPA’s job is not easy, though.

Coming to a state near you

Superintendents will be able to track state registrations on the PoaCure website. Don’t quote me, but it appears the product will be distributed directly from Moghu USA LLC to the client. Because herbicide use on golf greens carries relative risks, purchasers will be encouraged to visit the PoaCure website to complete a survey explaining their level of annual bluegrass infestation and turfgrass conditions. In exchange, the company will provide customized use recommendations for each client. Clients will also be strongly encouraged to test the product on their property before wide-scale use. I wish I could say PoaCure is foolproof, but there is no such thing when dealing with golf greens. As herbicides go, however, this one is as close as I’ve seen.

Funding

Partial funding for this research was provided by the Virginia Agricultural Council, the Virginia Turfgrass Foundation and Moghu Research Center.

The research says ...

- Ten years after it was first introduced to researchers in the U.S., methiozolin (PoaCure) has been approved as a “pre- and post-emergence grass herbicide for selective control of annual bluegrass and roughstalk bluegrass in golf course turf including creeping bentgrass putting greens.”

- The product is applied at very low rates and permits slow removal of Poa annua with minimal disruption of play.

- For successful use of PoaCure, it is necessary to know the level of Poa annua infestation and its predominant phenotype (annual vs. perennial), the prevalent environmental conditions, and pertinent maintenance practices.

- Key considerations are speed of control, turf safety issues, and turf recovery while preventing reinfestation and herbicide resistance.

- PoaCure SC has an unconditional registration, which means that it does not have a warning or “signal word” such as “caution” on the label. An additional formulation, PoaCure EC, has also been registered in the U.S., but the decision on whether to market this product in lieu of the SC formulation is pending.

Literature cited

- Askew, S.D., and B.M.S. McNulty. 2014. Methiozolin and cumyluron for preemergence annual bluegrass (Poa annua) control on creeping bentgrass (Agrostis stolonifera) putting greens. Weed Technology 28(3):535-542. doi:10.1614/WT-D-14-00018.1

- Brosnan, J., J. Vargas, G. Breeden, S. Boggess, M. Staton, P. Wadl and R. Trigiano. 2017. Controlling herbicide-resistant annual bluegrass (Poa annua) phenotypes with methiozolin. Weed Technology 31(3):470-476. doi:10.1017/wet.2017.13

- Hoisington, N., M. Flessner, M. Schiavon, J. McElroy and J. Baird. 2014. Tolerance of bentgrass (Agrostis) species and cultivars to methiozolin. Weed Technology 28(3):501-509. doi:10.1614/WT-D-13-00114-1

- Piper, C.V., and R.A. Oakley. 1921. Annual bluegrass (Poa annua). USGA Green Section Record, March 1921.

- Rana, S.S., and S.D. Askew. 2016. Response of 110 Kentucky bluegrass varieties and winter annual weeds to methiozolin. Weed Technology 30(4):965-978. doi:10.1614/WT-D-16-00089

- Rana, S.S., and S.D. Askew. 2017. Long-term roughstalk bluegrass control in creeping bentgrass fairways. Weed Technology 31(5):714-723. doi:10.1017/wet.2017.72

- Rana, S.S., and S.D. Askew. 2018a. Measuring canopy anomaly influence on golf putt kinematics: Errors associated with simulated putt devices. Crop Science 58(2):900-910. doi:10.2135/cropsci2017.03.0211

- Rana, S.S., and S.D. Askew. 2018b. Measuring canopy anomaly influence on golf putt kinematics: Does annual bluegrass influence ball roll behavior? Crop Science 58(2):911-916. doi:10.2135/

cropsci2017.03.0212

- Yu, J., and P.E. McCullough. 2014. Methiozolin efficacy, absorption, and fate in six cool-season grasses. Crop Science 54(3):1211-1219. doi:10.2135/cropsci2013.05.0349

Shawn Askew is an associate professor in the School of Plant and Environmental Sciences at Virginia Tech, Blacksburg, Va.