A tall fescue scalping timing research area at two weeks after treatment with glyphosate in fall 2016 at the John Seaton Anderson Turf Research Center near Mead, Neb. Photo by Cole Thompson

Clumps or patches of tall fescue can be objectionable in turfgrass species with contrasting leaf texture and color, such as Kentucky bluegrass or many warm-season grasses. While numerous selective herbicides are available for the control of cool-season perennial grasses such as tall fescue in warm-season turf, nonselective herbicides such as glyphosate are most commonly used to control tall fescue (Schedonorus arundinaceus; syn. Festuca arundinacea) in other cool-season grasses.

As part of a full-scale renovation, it is common to defoliate glyphosate-treated areas by “scalping” (that is, mowing at the lowest possible cutting height) after the leaves have necrotized from the herbicide application. However, scalping too soon before or after herbicide treatment may reduce herbicide efficacy, and university Extension resources and product labels commonly recommend delaying mowing (scalping) for up to seven days before or after treatment to maximize control. Although maximum control may result with limited vegetation disruption before or after a glyphosate application, these recommendations may be too conservative and limit flexibility for golf course superintendents.

Little work has been conducted to determine the best scalping practices for glyphosate use in turfgrass systems. Research on bulbous oatgrass (in a non-turfgrass system) revealed regrowth of glyphosate-treated plants was most limited, and not different, when defoliation occurred 24 to 192 hours after application (4). Many researchers have measured glyphosate translocation on various species, but researchers in these studies typically leave glyphosate on leaves for up to 72 hours to evaluate the effects of temperature, moisture stress, etc., on translocation with post-defoliation analyses (3).

Other researchers (1, 5) have evaluated the effects of mowing proximity to the application of herbicides other than glyphosate in routinely mowed turfgrass systems. These studies reported that mowing as soon as 30 minutes before or after applying herbicides did not reduce control of ground ivy (1), and that mowing four days before to four days after treatment did not reduce control of dandelion with a systemic broadleaf herbicide mixture (5).

Significant weed verdure following mowing was an important reason why the mowing treatments did not reduce control in these studies. However, little verdure may remain when scalping before or after a glyphosate application, which may potentially reduce herbicide absorption and translocation. Therefore, our objective was to more precisely define scalping restriction recommendations.

Our scalping timing experiment

We conducted field studies in 2016 and 2017 at the John Seaton Anderson Turf Research Center near Mead, Neb., and the Rocky Ford Turfgrass Research Center in Manhattan, Kan. Both sites had adequate soil moisture from irrigation and precipitation.

Our experiment included 5-by-5-foot (1.5-by-1.5-meter) plots of mature, turf-type tall fescue arranged in a randomized, complete-block design, with three replications in Nebraska and four replications in Kansas. The experiment was repeated in fall and spring at each site.

Glyphosate (GlyphoMate 41, PBI-Gordon) was applied at 6.4 pints of product/acre (7.8 liters/hectare) with a CO2-pressurized boom sprayer equipped with TeeJet 8002VS nozzles calibrated to deliver 22 gallons/acre at 35 psi (205.8 liters/hectare at 241.3 kilopascals). Fall and spring glyphosate application dates were Oct. 11, 2016, and May 8, 2017, respectively, in Nebraska, and Oct. 18, 2016, and May 5, 2017, respectively, in Kansas. All plots were maintained at 3 inches (7.6 centimeters) before and after treatment initiation.

To test the effects of scalping timing on the glyphosate application, plots were scalped to approximately 1 inch (2.5 centimeters) at one day before treatment with glyphosate, one hour before treatment with glyphosate, one hour after treatment with glyphosate, or one, two, three, four or five days after treatment with glyphosate. A non-treated control (no glyphosate applied and no scalping treatment applied) was included for comparison, and nine treatments were evaluated in total. Glyphosate has been shown to be active in clippings collected within three days of application (2), so clippings were collected in this study.

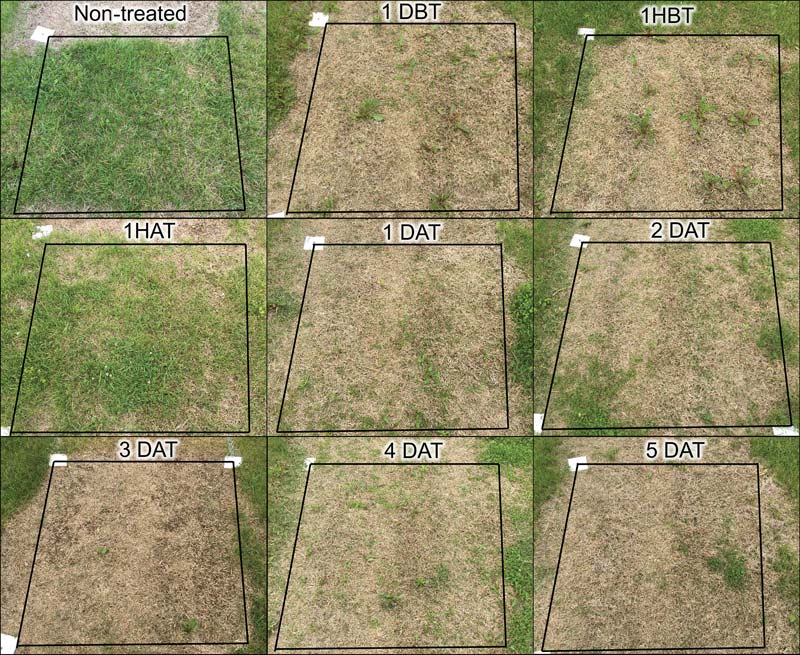

Figure 2. Effects of scalping timing on tall fescue green cover on May 23, 2017, at 32 weeks after treatment with glyphosate in fall in Mead, Neb. Scalping timing treatments occurred at one day before treatment (1DBT) with glyphosate, one hour before treatment (1HBT), one hour after treatment (1HAT), or one, two, three, four or five days after treatment (DAT) with glyphosate. Green areas are dandelion and white clover weed seedlings except in non-treated and 1HAT plots.

For both fall and spring timings, percent tall fescue green cover was visually estimated at zero, one, two, four and eight weeks after treatment with glyphosate, and additional ratings were collected at 24 and 32 weeks after treatment for the fall timings after winter dormancy. At both sites, tall fescue green cover was 100% at zero weeks after treatment for both the fall and spring timings. Each application timing (fall or spring) was analyzed separately.

The fall analysis was combined across locations because our central objective was to estimate treatment effects. The spring analysis was not combined across locations because glyphosate was inadvertently applied to non-treated control plots in Nebraska. However, researchers observed no decline in the non-treated tall fescue turf surrounding the study area and are confident that the spring responses in Nebraska were from the applied treatments.

Fall timing

Following glyphosate treatment in fall across both locations, all scalping timings except one hour after treatment with glyphosate significantly reduced tall fescue green cover compared with the non-treated control (97% tall fescue green cover at 32 weeks after treatment) from two to 32 weeks after treatment (Figure 1; Figure 2, above). At 32 weeks after treatment, glyphosate efficacy was not reduced when turf was scalped one to five days after treatment (0% to 3% tall fescue green cover by 32 weeks after treatment), but scalping tall fescue one day before, one hour before or one hour after treatment with glyphosate failed to reduce tall fescue cover to less than 20%.

Spring timing

Scalping one, three, four or five days after treatment with glyphosate in spring reduced tall fescue green cover to less than 8% at eight weeks after treatment in Nebraska (Figure 3). Plots scalped one day before, one hour before, or one hour after glyphosate application had significantly greater tall fescue green cover at this time (65% to 78% cover). Meanwhile, scalping two days after treatment with glyphosate resulted in 12% tall fescue green cover at eight weeks after treatment, not different from all the other scalping timings. The inadvertent glyphosate-treated control, which was never scalped, was also not different from all other treatments and demonstrates that treating with glyphosate but never scalping provided no better tall fescue control than when plots were scalped following treatment.

In Kansas, all scalping timings except scalping one hour before or one hour after treatment with glyphosate reduced tall fescue green cover to 0% to 8% at eight weeks after treatment, significantly less than the non-treated control (100% green cover) (Figure 4).

Take-home message

Overall, our results for both spring and fall timings indicate that tall fescue control with glyphosate is not reduced by scalping as soon as one day following treatment. We speculate that herbicide translocation was fast enough for a sufficient concentration of glyphosate to accumulate in the meristems of 3-inch tall fescue in as little as 24 hours post-application. We hypothesize a similar amount of time may also be sufficient for lower turf mowing heights, although this requires further investigation.

Further, because glyphosate has been shown to be active in clippings (2), care must be taken within three days of application to exclude clippings from non-treated areas.

Tall fescue at the Rocky Ford Turfgrass Research Center in Manhattan, Kan. Photo by Ross Braun

Our results also indicate that scalping the turf and removing clippings immediately after (that is, within one hour) an accidental application of glyphosate may be a good strategy to mitigate turf injury. We recommend following label instructions for maximum efficacy, but suggest that scalping tall fescue as soon as one day following treatment with glyphosate will not reduce efficacy compared with delaying scalping until at least three days after treatment (as is often recommended), which could benefit golf course superintendents who have a short window of time for renovations in the spring or fall.

Funding

This research was supported by funding from the Nebraska Turfgrass Association and the Kansas Turfgrass Foundation.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Benjamin Van Ryzin and Nic Mitchell for assistance with this project. The full manuscript on the experiment is available in Crop, Forage & Turfgrass Management.

The research says ...

- Scalping tall fescue from one hour before to one hour after glyphosate treatment reduces herbicide efficacy.

- In both fall and spring, tall fescue control with glyphosate is not reduced by scalping as soon as one day following treatment, which is two days sooner than what is typically recommended.

- Scalping the turf and removing clippings within one hour after an accidental application of glyphosate may be a good strategy to mitigate turf injury.

Literature cited

- Beck, L.L., A.J. Patton and D.V. Weisenberger. 2014. Mowing before or after an herbicide application does not influence ground ivy (Glechoma hederacea) control. Applied Turfgrass Science 11:1-5. doi:10.2134/ATS-2013-0017-RS

- Goss, R.M., R.E. Gaussoin and A.R. Martin. 2004. Phytotoxicity of clippings from creeping bentgrass treated with glyphosate. Weed Technology 18:575-579. doi:10.1614/WT-03-093R2

- McWhorter, C.G., T.N. Jordan and G.D. Wills. 1980. Translocation of 14C-glyphosate in soybeans (Glycine max) and Johnsongrass (Sorghum halepense). Weed Science 28:113-118.

- Tanphiphat, K., and A.P. Appleby. 1990. Absorption, translocation, and phytotoxicity of glyphosate in bulbous oatgrass (Arrhenatherum elatius var. bulbosum). Weed Science 38:480-483.

- Thompson, C.S., R.C. Braun, J.A. Hoyle and B. Van Ryzin. 2018. Mowing timing does not affect the efficacy of broadleaf herbicides applied to control dandelion (Taraxacum officinale). Crop, Forage & Turfgrass Management 4:170074. doi:10.2134/cftm2017.10.0074

Ross C. Braun is the lead research scholar in the Department of Horticulture and Landscape Architecture at Purdue University, West Lafayette, Ind; Cole S. Thompson is the assistant director of Green Section research for the United States Golf Association, Dallas; and Jared A. Hoyle is an associate professor in the Department of Horticulture and Natural Resources at Kansas State University, Manhattan, Kan.