Figure 1. Robust, black mycelium of Curvularia malina may be observed colonizing infected stems and leaves of bermudagrass and zoysiagrass. Photo by Maria Tomaso-Peterson

In the late 2000s, golf course superintendents in the greater Houston metropolitan area were seeing a foliar patch disease on bermudagrass and zoysiagrass greens, tee boxes and fairways. Because a primary symptom of the disease was small, dark, brownish-black patches, the disease was called “ink spot.”

During that time, Mississippi State University received a sample for disease diagnosis that had been taken from a Tifgreen (also known as 328 or Tifton 328) bermudagrass putting green with a distinct chocolate-brown patch in the turf canopy. Black lesions were present on the leaves. The symptoms in the diseased turf sample were unlike any I had observed.

Infected leaves were plated onto water agar, a nutrient-deficient medium that promotes fungal reproduction. Within 36 hours, black, robust mycelium of the pathogen was growing out of the leaf tissue. In pure culture, the fungus was black and sterile; no reproductive structures developed that would aid in fungal identification.

In that same growing season, samples of this conspicuous disease were received from bermudagrass putting greens, tee boxes and fairways as well as zoysiagrass fairways. In the ensuing years, turfgrass pathologists at Mississippi State University and Texas A&M University independently isolated a darkly pigmented sterile fungus from lesions associated with chocolate-brown to black spots occurring in golf course samples from the region.

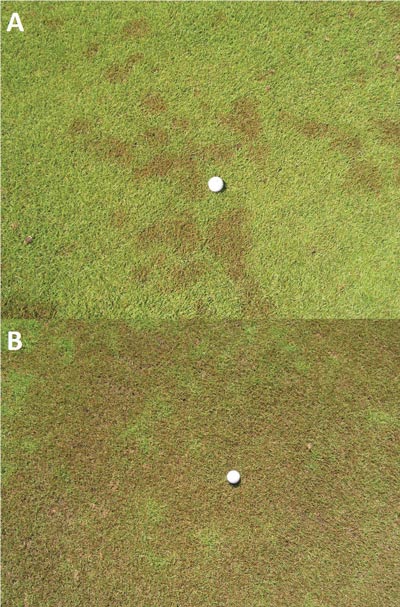

Right: Figure 2. Foliar symptoms of ink spot on a zoysiagrass fairway. A: Ink spot first appears as chocolate-brown to black spots less than 1 inch to 6 inches (2-15 cm). B: Under ideal disease conditions, ink spot symptoms may coalesce, creating large areas of mottled brown to black turf. Photos by Billy Weeks

Dr. Young-Ki Jo at Texas A&M and I began a collaborative effort to characterize ink spot and the undescribed causal agent. As samples came into the lab, our living culture collection increased in number. However, because the fungal pathogen is sterile, we used molecular methods for identification purposes.

Amplification of the universal DNA barcode gene of fungi, the internal nuclear ribosomal transcribed spacer region (ITS), was the first step toward identification. The amplified ITS product was sequenced and uploaded into GenBank, a genetic sequence database. The initial ITS match was an undescribed fungal pathogen from Japan associated with dog’s footprint disease in zoysiagrass.

In the 1997 book Color Atlas of Turfgrass Diseases (1), a foliar disease of zoysiagrass in Japan showed turf symptoms identical to those of ink spot in the United States. It was identified as Curvularia blight. Among the pathogens associated with Curvularia blight is a black sterile fungus that was not fully characterized in the book. As time progressed, we received pictures and samples of ink spot from golf courses in Alabama, Mississippi, Tennessee and Hainan Province in China, broadening our understanding of the distribution of the disease. Because the sterile fungal pathogen causing ink spot was undescribed, a comprehensive phylogenetic analysis was employed, resulting in the identification of a novel fungal species (2).

The ink spot pathogen

A novel species of Curvularia was identified as the foliar pathogen of bermudagrass and zoysiagrass in the southeastern United States (2). Curvularia malina sp. nov. (meaning “black,” “dirty,” “stained”) refers to the mycelium and symptoms in the turf. The black, net-like mycelium of C. malina can be observed under low magnification on the outer surface of infected leaves and stems (Figure 1, top).

As indicated, the fungus is sterile, and it therefore develops no asexual conidia, unlike its very distant relatives, C. lunata and C. geniculata, which are prolific conidia producers. The optimal growing temperature of C. malina is 77 F (25 C). The fungus proliferates under ideal temperature and moisture conditions, allowing for rapid identification in culture.

Symptoms and climatological conditions favorable for ink spot

Figure 3. Foliar symptoms of ink spot caused by Curvularia malina include conspicuous elliptical lesions with black margins on zoysiagrass. Lesions may expand across and down the leaf to cause blight. Photo by Maria Tomaso-Peterson

Symptoms

On bermudagrass and zoysiagrass managed under golf course conditions, ink spot presents as conspicuous chocolate-brown to black spots that range in size from less than 1 inch to 6 inches (2-15 cm). As the disease progresses, the spots coalesce to form large, irregular areas of blighted turf (Figure 2). The leaves of affected plants initially display small, purplish-black spots that develop into distinct eyespot lesions with necrotic, dark brown centers surrounded by dark brownish-black margins (Figure 3). The older blighted leaves in the lower canopy of the turf give rise to the chocolate-brown to black spots observed in the turfgrass stand. Spots resulting from fall epidemics may remain conspicuous within the dormant turf, maintaining the sooty black appearance until spring green-up (Figure 4, below).

Figure 4. During fall epidemics of ink spot, black, sooty patches may remain in the turf canopy throughout dormancy and recur during spring green-up. Photo by Maria Tomaso-Peterson

Ink spot is most prevalent in the spring and fall, which are transition periods for bermudagrass and zoysiagrass, but the disease may persist into the summer months that follow prolonged or significant precipitation events such as tropical storms or hurricanes. “Curvularia blight” or “dog’s footprint” (inu no ashiato; Japanese translation) are turfgrass diseases caused by the same pathogen, C. malina, as Micah Woods, Ph.D., concluded in the Asian Turfgrass Center Blog (3).

Climate

Anecdotal sightings and a published first report (Hainan Province, China) of disease caused by C. malina appear to indicate that diseases caused by C. malina are geographically confined to regions influenced by the subtropical ridge associated with 30ºN. The 30th parallel north is considered arid to semiarid, but locales in that area that are influenced by large bodies of water have a more tropical environment and form what is called the “subtropical ridge.” These regions include the Gulf and Atlantic United States, South China, southern Japan and southern Queensland, Australia. Currently, no reports of ink spot have been made outside the 30th parallel north.

Ink spot host species

To conclude the characterization of C. malina and ink spot, a host-range study of warm-season turfgrasses was conducted at Mississippi State University. In greenhouse studies, zoysiagrass was more susceptible than all the other warm-season grasses evaluated, including bermudagrass.

Figure 5. Pathogenicity of Curvularia malina to warm-season turfgrass species: zoysiagrass (top), centipedegrass (center) and seashore paspalum (bottom). All three photos show seedlings in C. malina-infested (left) and non-infested (right) potting mix at five weeks after planting. In all three cases, seedling density was reduced in the C. malina-infested potting soil. Photos by Maria Tomaso-Peterson

Centipedegrass and St. Augustinegrass developed foliar lesions, but foliar leaf blight was not extensive. Seashore paspalum did not develop foliar lesions, but shoot and root dry weights were significantly reduced compared with the check (Figure 5.) Currently, field symptoms of ink spot have been observed only on bermudagrass and zoysiagrass, with the latter appearing more susceptible in the southern United States.

Golf course superintendents have had success managing ink spot with fungicides labeled for Curvularia species. However, efficacy trials that include the new generation of succinate dehydrogenase inhibitor (SDHI) fungicides as well as fertility studies that include nitrogen source and rates may benefit superintendents who are trying to reduce outbreaks of ink spot caused by C. malina.

Funding

This research is a contribution of the Mississippi Agricultural and Forestry Experiment Station and the National Institute of Food and Agriculture, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Hatch project under accession number 213130.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to all the golf course superintendents in Houston who provided turfgrass samples for the diagnosis and characterization of ink spot and Curvularia malina.

The research says ...

- A disease of warm-season grasses was discovered in the Houston area in the late 2000s.

- Because the primary disease symptom was patches in the turf ranging from dark brown to black along with black foliar lesions, the disease was called “ink spot.”

- Phylogenetic analysis was used to identify the fungal pathogen for ink spot, which was considered a novel pathogen and named Curvularia malina.

- Ink spot has been found only in the 30th parallel north.

- Further research is needed to determine which management practices or products will reduce or control disease occurrence.

Literature cited

- Tani, T., and J.B. Beard. 1997. Color Atlas of Turfgrass Diseases, First Edition. Ann Arbor Press, Chelsea, Mich.

- Tomaso-Peterson, M., J. Young-Ki, P.L. Vines and F.G. Hoffman. 2016. Curvularia malina sp. nov. incites a new disease of warm-season turfgrasses in the southeastern United States. Mycologia 108(5):915-924.

- Woods. M. 2016. Dog’s footprint and turfgrass susceptibility to this disease. Viridescent: The Asian Turfgrass Center Blog. Sept. 19, 2016.

Maria Tomaso-Peterson is a research professor in plant pathology at Mississippi State University, Mississippi State, Miss.