Annual bluegrass greens are often severely damaged by winterkill in the northern United States, and replacing the turf in a timely manner may be difficult. Photos by Kevin Frank

Editor’s note: This research was funded in part by a grant to GCSAA from the Environmental Institute for Golf.

Winterkill is a general term that is used to define turf loss during the winter (1). Winterkill can be caused by a combination of factors, including crown hydration, desiccation, low-temperature kill, ice sheets and snow mold. Because environmental factors are unpredictable and other factors such as surface drainage are variable, the occurrence of winterkill can vary greatly between golf courses and even across the same golf course.

In general, annual bluegrass (Poa annua) greens and fairways are the most susceptible to crown hydration injury and anoxia injury from ice sheet cover. Potential for crown hydration injury exists when a day or two of warm daytime temperatures in late winter is followed by a rapid freeze. The freezing temperatures cause water to move out of the cells into the extracellular area, where it freezes. It is believed that cell dehydration — not ice formation — in the extracellular area kills the crown (11, 12). Sporadic crown hydration injury on annual bluegrass occurs almost every year somewhere in the northern United States.

Prolonged ice cover causes another type of low-temperature kill. Ice cover on putting greens during the winter of 2013-2014 caused extensive winterkill throughout the Great Lakes region of the United States (4). The primary cause of winterkill from ice sheets is from toxic gas accumulation or oxygen depletion resulting in anaerobic conditions (14). Ice cover and crown hydration are the two primary causes of annual bluegrass death over winter.

Re-establishment after winterkill

Winterkill has no defined pattern; damage may be sporadic or complete, making re-establishment difficult. Re-establishing following winterkill can also be challenging because of cool spring temperatures and the demand for spring golf that results in traffic on winterkill areas (13).

If creeping bentgrass (Agrostis stolonifera L.) is killed, seeding or sodding are viable options for re-establishment. However, if annual bluegrass is killed, commercially available annual bluegrass seed is limited to one cultivar, DW-184 (1), and annual bluegrass sod is not readily available in most locations. Some golf courses maintain annual bluegrass nurseries for sodding if their annual bluegrass is killed.

When an annual bluegrass nursery is not available or not large enough to repair all the damage, creeping bentgrass is commonly seeded into damaged areas. Golf course superintendents have also experimented with collecting clippings containing annual bluegrass florets (commonly called seed) from annual bluegrass putting greens and spreading them on dead areas to re-establish annual bluegrass (7).

For the purposes of this study, a creeping bentgrass green was sprayed several times with glyphosate in order to simulate winterkill.

Annual bluegrass is unique in that seeds can ripen on panicles severed from the mother plant on the same day that pollination occurs (5). Annual bluegrass seed germinates over a temperature range of 40 F to 70 F (4.5 C to 21 C) (3), and annual bluegrass germination has been reported in the fall and spring, and to a lesser extent throughout the entire growing season, in Michigan (2).

Re-establishment in the spring when temperatures are below optimum for creeping bentgrass germination is difficult (13), because the optimal air temperature range for creeping bentgrass germination is 59 F to 86 F (15 C to 30 C), with a soil temperature of 59 F to 77 F (15 C to 25 C) (15). Many different cover systems have been used to raise canopy and soil temperatures to hasten establishment, including permeable geotextile, clear polyethylene and cotton grow covers (6, 8, 10, 16).

We conducted research to determine the effects of fertilizer treatments, protective covers, and seeding creeping bentgrass or annual bluegrass on putting green re-establishment following simulated winterkill.

Materials and methods

Research was conducted in 2007 and 2008 at the Hancock Turfgrass Research Center (HTRC) at Michigan State University. To simulate winterkill, a creeping bentgrass putting green was sprayed with glyphosate several times before seeding to ensure complete kill of the existing turf stand.

The putting green was prepared for seeding using the Miltona Turf Tools Jobsaver aerator attachment on a Jacobsen GA-30 aerator. The Jobsaver attachment creates cone-shaped depressions in the putting green to enhance seed establishment.

Seeding

Penn A-4, Providence and Alpha creeping bentgrass were seeded at 2 pounds/1,000 square feet (10 grams/square meter). Annual bluegrass florets were collected from an annual bluegrass putting green at the HTRC by mowing at a height of 0.16 inch (4 mm) on April 17, 2007, and April 28, 2008. The clipping-floret mixture was applied at 2 pounds/1,000 square feet to each plot receiving the annual bluegrass seeding treatment.

The creeping bentgrass cultivars were seeded on April 21, 2007, and May 2, 2008, and the annual bluegrass clipping-floret mixture was applied to the plots on May 4, 2007, and May 9, 2008. The delay in applying the clipping-floret mixture was due to timing of annual bluegrass floret production in the annual bluegrass green at the HTRC. Immediately following seeding, sand topdressing was applied at 115 pounds/1,000 square feet (562 grams/square meter), and starter fertilizer (19N-25P-5K) was applied at 1 pound nitrogen/1,000 square feet (5 grams/square meter), followed by 0.5 inch (12 mm) of irrigation.

Cover treatments

To test the effects of covers on turf recovery, plots remained uncovered or, if forecast temperatures were below 50 F (10 C), were covered from late evening until 8 a.m. the following day.

Creeping bentgrass seedling emergence was on May 10, 2007, and May 14, 2008. Cover treatments (a clear polyethylene cover or a non-covered control) were initiated upon creeping bentgrass seedling emergence. Plots were covered when nighttime temperatures were forecast below 50 F (10 C). Covers were applied in the late evening, with approximately two hours of sunlight remaining. The covers were removed for the day by approximately

8 a.m. the following morning in order to simulate golf course putting greens that were kept open for play during re-establishment.

Fertilization programs

Fertilization programs were also initiated upon creeping bentgrass seedling emergence. There were two fertilizer treatments. A urea (46N-0P-0K) solution was sprayed at 0.1 pound nitrogen/1,000 square feet (0.5 gram/square meter) every seven days, and a granular starter fertilizer (19N-25P-5K) was applied at 0.3 pound nitrogen/1,000 square feet (1.5 grams/square meter) every 21 days.

Fertilizer treatments were applied to the turf plots for 11 weeks after turf emergence. Beginning at two weeks after emergence, the plots were mowed five days a week.

Fertilizer treatments were applied for 11 weeks after emergence in both years. Irrigation was applied three times daily from April 21 to 30 in 2007, and from May 2 to 14 in 2008, and then every other day for the remainder of the research for both years. Irrigation amounts were calculated to return 75% of reference potential evapotranspiration (ETp) estimated by the FAO Penman-Monteith equation from an on-site weather station. Two weeks after emergence, plots were mowed five days a week at a height of 0.25 inch (7 mm). Mowing height was lowered by approximately 0.4 inch (10 mm) each subsequent week to reach 0.12 inch (3 mm) at six weeks after emergence.

The experimental design was a randomized complete block with three replications. Data were analyzed as a four-factor experiment, with year, turfgrass species and creeping bentgrass cultivar, fertilizer program and cover treatment as factors. Statistical analysis indicated the results for each year were significantly different, so data were separated by year and analyzed as a three-factor experiment.

Results and discussion

Species and cultivar effects

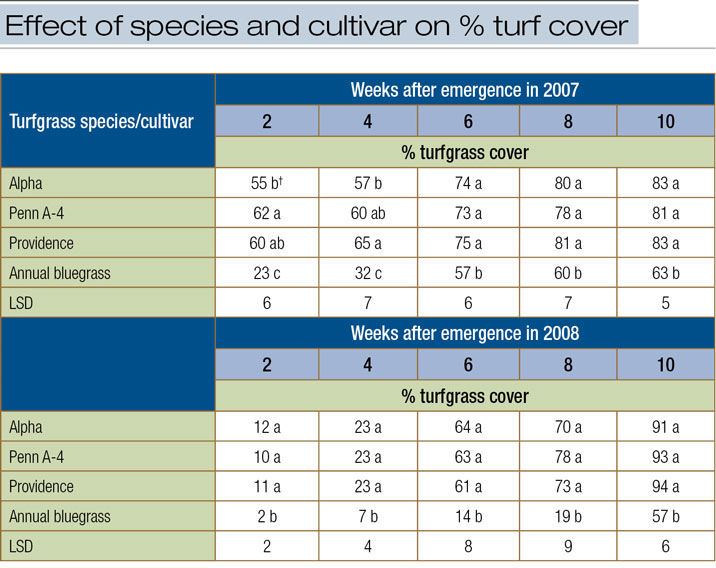

There were differences in turf cover between turfgrass species and among creeping bentgrass cultivars on all dates in 2007 and 2008 (Table 1, below). The annual bluegrass treatment had the lowest percent turfgrass cover on all dates in both years. The annual bluegrass treatment had 63% cover at 10 weeks after emergence in 2007, and 57% cover in 2008.

†Within a column, means followed by the same letter are not significantly different.

Table 1. Effect of turfgrass species and creeping bentgrass cultivar treatment on percent turfgrass cover in 2007 and 2008.

In 2007, there were significant differences among creeping bentgrass cultivars at two and four weeks after emergence. At two weeks after emergence, Penn A-4 and Providence had the highest percent turfgrass cover. Alpha had lower percent cover than Penn A-4, but did not differ from Providence.

All creeping bentgrass cultivars had higher percent cover than the annual bluegrass treatment. At four weeks after emergence, Providence and Penn A-4 had the highest percent turfgrass cover, and there was no difference between Penn A-4 and Alpha. There were no differences among creeping bentgrass cultivars at six, eight and 10 weeks after emergence in 2007, and there were no differences among creeping bentgrass cultivars on any date in 2008.

Establishment of four creeping bentgrass cultivars and an unseeded control was measured on a soil with an established seed bank of annual bluegrass in an earlier research project at Rutgers University in New Jersey (9). Creeping bentgrass seeded in June established more quickly than the unseeded control. However, there were no differences in establishment rate between seeded creeping bentgrass and the unseeded control in September and October plantings (9). The authors concluded this result was due to higher soil temperatures in the summer that suppressed annual bluegrass germination. Although we did not test the effect of spring or summer seeding versus fall, our results appear to agree with the Rutgers results in that annual bluegrass establishment was relatively poor when compared to establishment of seeded creeping bentgrass.

Our results indicate that the three creeping bentgrass cultivars that we tested showed essentially no difference in establishment rate following a simulated winterkill event. Our effort to establish annual bluegrass using collected florets was relatively ineffective, with just over 50% of the plot area established at six weeks after emergence in 2007 and at 10 weeks after emergence in 2008.

Effects of temperature

Creeping bentgrass showed large differences in percent turfgrass cover at two and four weeks after emergence between 2007 and 2008. At two weeks after emergence, the creeping bentgrass cultivars had a mean percent cover of 59% in 2007 and 11% in 2008.

The difference in percent cover was likely caused by temperature differences following seedling emergence. The mean high air temperature in the first two weeks after emergence was 73 F (23 C) in 2007 and 64 F (18 C) in 2008. The mean soil temperature at the 2-inch (51 mm) depth in the first two weeks after emergence was 61 F (16 C) in 2007 and 57 F (14 C) in 2008. Because the seed was broadcast and incorporated to a shallow depth of 0.5 inch (12.7 mm), air temperatures had a greater effect on establishment than soil temperatures.

Our results indicate the date of seeding is less important than the temperatures following seedling emergence. In 2007, the creeping bentgrass seeding date was April 21, with emergence on May 10, an interval of 19 days. In 2008, the creeping bentgrass seeding date was May 2, with emergence on May 14, an interval of 12 days. Although the seeding date was earlier in 2007, days to emergence took longer than in 2008, and our results suggest that warmer temperatures in 2007 had a greater influence on speed to early establishment than an earlier seeding date.

Effects of fertilizer program

Throughout the research, fertilizer treatments produced few differences. There were differences in percent turfgrass cover on only two dates in 2007, four and five weeks after emergence (data not presented). On each date, the starter fertilizer program had the highest percent turfgrass cover. However, the numerical difference in percent turfgrass cover between the two programs was small.

At four weeks after emergence, percent turfgrass cover was 48% for the urea fertilizer program and 50% for the starter program. At five weeks after emergence, percent turfgrass cover was 62% for the urea program and 68% for the starter fertilizer program.

Cover effects

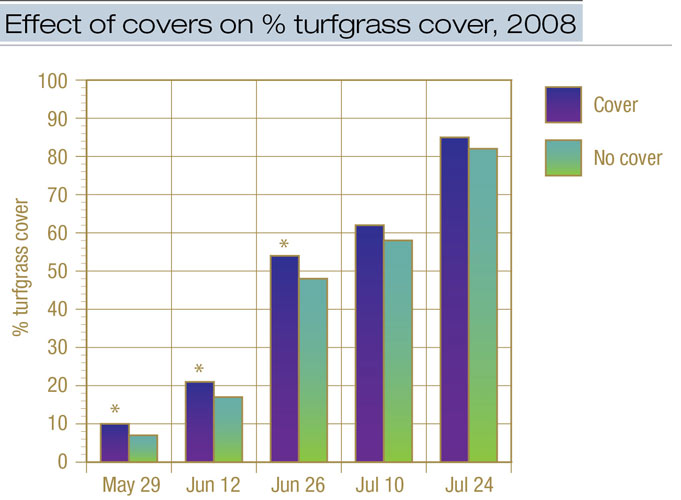

Cover treatment had no significant effects on percent turfgrass cover in 2007, but there were significant cover treatment effects in 2008 on three dates (Figure 1, below).

Figure 1. After creeping bentgrass seedling emergence in 2008, the effect of protective covers on % turfgrass cover was examined by comparing plots that were not covered with plots that were covered with clear polyethylene covers from late evening until 8 a.m. An asterisk indicates that the treatment plots with a polyethylene cover had a significantly higher percentage of turfgrass cover than the plots without a cover. No significant differences were seen in July.

From two through six weeks after emergence in 2008, the polyethylene cover treatment had higher percent turfgrass cover than the uncovered treatment. Although there were significant differences, the mean difference in percent cover between the polyethylene cover and no cover treatment was small: 5%.

The polyethylene cover treatment was used on 19 days in May 2007 and 27 days in May 2008. The difference in night air temperatures between the two years resulted in small but significant differences between cover treatments from two through six weeks after emergence in 2008.

Leaving covers in place during the day may have increased temperatures under the cover and possibly decreased the time for establishment, but leaving a clear polyethylene cover in place during the day may elevate temperatures to the level that turf establishment is reduced either by disease or by smothering (13, 16). Further research on cover types and duration of cover is necessary to improve our understanding of how covers may be used to enhance establishment following winterkill.

Acknowledgments

The authors express thanks to GCSAA, the Environmental Institute for Golf, the Michigan Turfgrass Foundation, Michigan State University Project GREEEN and the Northern Great Lakes GCSA for funding.

The research says ...

- We evaluated the effects of fertilizer treatments, protective covers, and seeding creeping bentgrass or annual bluegrass on putting green re-establishment following simulated winterkill.

- The effort to establish annual bluegrass using collected florets was relatively ineffective, with just over 50% of the plot area established at six and 10 weeks after emergence in 2007 and 2008, respectively.

- The creeping bentgrass cultivars tested showed essentially no difference in establishment rate, but our results suggest that warmer temperatures in 2007 had a greater influence on speed to early establishment than an earlier seeding date.

- The two fertilizer treatments produced few differences, and those differences were small. On each date, the starter fertilizer program had the highest percent turfgrass cover.

- On three dates in 2008, the polyethylene cover treatment had higher percent turfgrass cover than the uncovered treatment, but the mean difference was only 5%.

Literature cited

- Beard, J.B., and H.J. Beard. 2005. Beard’s Turfgrass Encyclopedia for Golf Courses, Grounds, Lawns, Sports Fields. Michigan State University Press, East Lansing, Mich.

- Branham, B.E. 1991. Dealing with Poa annua: Understanding the strength and weaknesses of annual bluegrass is the first step in developing a successful management program. Golf Course Management 59(9):46-60.

- Calhoun, R.N. 2010. Growing degree-days as a method to characterize germination, flower pattern, and chemical flower suppression of a mature annual bluegrass [Poa annua var. reptans (Hauskins) Timm] fairway in Michigan. Ph.D. dissertation, Michigan State University, East Lansing.

- Frank, K.W. 2014 Turfgrass winterkill observations from the Great Lakes region. Applied Turfgrass Science doi:10.2134/ATS-2014-0057-BR

- Koshy, T.K. 1969. Breeding systems in annual bluegrass, Poa annua L. Crop Science 9:40-43.

- Lettner, R.G. 1988. Geotextiles can enhance spring green-up of fine bentgrass greens. Golf Course Management 56(12):28-33.

- Miltner, E.D., G.K. Stahnke, G.J. Rinehart and P.A. Backman. 2005. Seeding of creeping bluegrass into existing golf course putting greens. HortScience 40:457-459.

- Minner, D.D., D. Li and F. Valverde. 2001. The effect of winter covers on autumn established Kentucky bluegrass. Iowa Turfgrass Research Report 94-97.

- Murphy, J.A., H. Samaranayake, T.J. Lawson, J.A. Honig and S. Hart. 2005. Seeding date and cultivar impact on establishment of bentgrass in soil containing annual bluegrass seed. International Turfgrass Society Research Journal 10:410-415.

- Patton, A.J., J.M. Trappe and M.D. Richardson. 2010. Cover technology influences warm-season grass establishment from seed. HortTechnology 20(1):153-159.

- Rossi, F.S. 1997. Physiology of turfgrass freezing stress injury. Turfgrass Trends 6(2):1-8.

- Skorulski, J. 2002. The greatest challenge. USGA Green Section Record 40(5):1-6.

- Snow, J.T. 1979. Promoting recovery from winter injury. USGA Green Section Record 17(1):11-13.

- Tompkins, D.K., J.B. Ross and D.L. Moroz. 2004. Effects of ice cover on annual bluegrass and creeping bentgrass putting greens. Crop Science 44:2175-2179.

- Toole, V.K., and E.J. Koch. 1977. Light and temperature controls of dormancy and germination in bentgrass seeds. Crop Science 17:806-811.

- Vavrek, B. 2005. Slow recovery. USGA Turf Management Regional Updates. (web.archive.org/web/20070807234015/http://www.usga.org/turf/regional_updates/regional_reports/northcentral/05-16-2005.html) Accessed April 1, 2016.

Kevin W. Frank is an associate professor and Extension turf specialist, and Joe Vargas Jr. is a professor in the Department of Plant, Soil and Microbial Sciences at Michigan State University, East Lansing, Mich. Erica Bogle was a graduate research assistant, and Jeff Bryan was a research technician at Michigan State and participated in this research project.